Vector Search with FAISS: Approximate Nearest Neighbor (ANN) Explained

Table of Contents

- Vector Search with FAISS: Approximate Nearest Neighbor (ANN) Explained

- From Exact to Approximate: Why Indexing Matters

- The Trouble with Brute-Force Search

- The Curse of Dimensionality

- Enter the Approximate Nearest Neighbor (ANN)

- Accuracy vs. Latency: The Core Trade-Off

- What You’ll Learn Next

- What Is FAISS?

- Why We Need Index Structures

- Flat Index: The Exact Baseline

- IVF-Flat: Coarse Clustering for Speed

- HNSW: Navigable Graph Search

- Comparing the Three Index Types

- What You’ll Do Next

- pyimagesearch/config.py (what we use in Lesson 2)

- pyimagesearch/vector_search_utils.py

- 02_vector_search_ann.py (driver)

Vector Search with FAISS: Approximate Nearest Neighbor (ANN) Explained

In this tutorial, you’ll learn how vector databases achieve lightning-fast retrieval using Approximate Nearest Neighbor (ANN) algorithms. You’ll explore how FAISS structures your embeddings into efficient indexes (e.g., Flat, IVF, and HNSW), benchmark their performance, and see how recall and latency trade off as your dataset scales.

This lesson is the 2nd of a 3-part series on Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG):

- TF-IDF vs. Embeddings: From Keywords to Semantic Search

- Vector Search with FAISS: Approximate Nearest Neighbor (ANN) Explained (this tutorial)

- Lesson 3

To learn how to scale semantic search from milliseconds to millions of vectors, just keep reading.

From Exact to Approximate: Why Indexing Matters

In the previous lesson, you learned how to turn text into embeddings — compact, high-dimensional vectors that capture semantic meaning.

By computing cosine similarity between these vectors, you could find which sentences or paragraphs were most alike.

That worked beautifully for a small handcrafted corpus of 30-40 paragraphs.

But what if your dataset grows to millions of documents or billions of image embeddings?

Suddenly, your brute-force search breaks down — and that’s where Approximate Nearest Neighbor (ANN) methods come to the rescue.

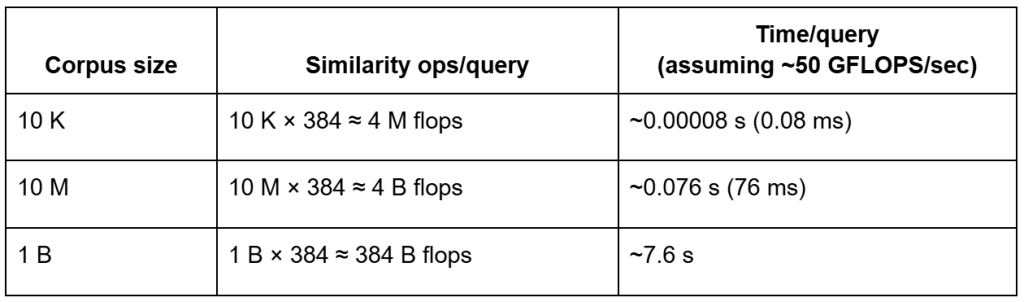

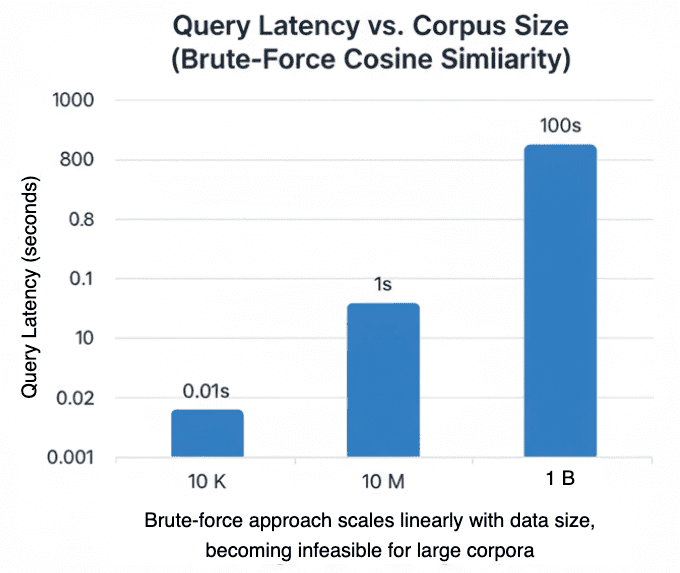

The Trouble with Brute-Force Search

In Lesson 1, we compared every query vector against all stored embeddings

using cosine similarity:

If your dataset contains vectors, this means

dot products for each query — an operation that scales linearly as

.

That’s fine for 500 vectors, but catastrophic for 50 million.

Let’s do a quick back-of-the-envelope estimate:

ᯈ50 GFLOPS/sec effective CPU throughput.Even on modern hardware capable of tens of gigaflops (GFLOPS) per second, brute-force search over billions of vectors still incurs multi-second latency per query — before accounting for memory bandwidth limits — making indexing essential for production-scale retrieval.

The Curse of Dimensionality

High-dimensional data introduces another subtle problem: distances begin to blur.

In 384-dimensional space, most points are almost equally distant from each other.

This phenomenon, called the curse of dimensionality, makes “nearest neighbor” less meaningful unless your metric is very carefully chosen and your embeddings are normalized.

🧠 Intuition: imagine scattering points on a 2D plane — you can easily tell which ones are close.

In 384D, everything is “far away,” so naive distance computations lose discriminative power.

That’s why normalization (L2) is critical — it keeps embeddings on a unit hypersphere, letting cosine similarity focus purely on angle, not length.

But even with normalization, you still can’t escape the sheer computational load of checking every vector.

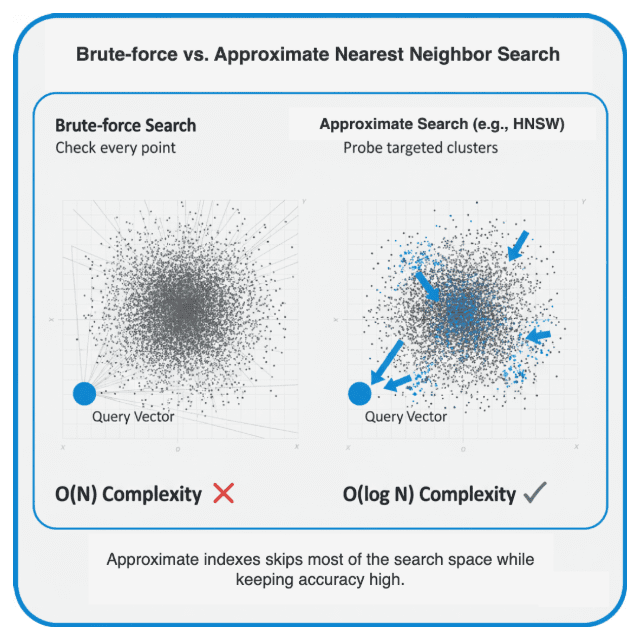

Enter the Approximate Nearest Neighbor (ANN)

So, how do we search faster without comparing against every vector?

Approximate Nearest Neighbor (ANN) algorithms do exactly that.

They trade a small amount of accuracy (recall) for huge latency gains — often 100× faster.

Conceptually, they build an index that helps jump directly to promising regions of vector space.

Think of it like finding a book in a massive library:

- Brute-force search: opening every book until you find the right topic.

- Indexed search: using the catalog — you might not find the exact match every time, but you’ll get very close, much faster.

Accuracy vs. Latency: The Core Trade-Off

ANN methods exist in many flavors — graph-based (HNSW), cluster-based (IVF), tree-based (LSH, KD-Tree), and hybrid approaches — but they all share a single philosophy:

They do so by:

- Pre-structuring the vector space (clustering, graphs, hashing).

- Restricting comparisons to only nearby candidates.

- Accepting that some true neighbors might be missed — in exchange for massive speed-ups.

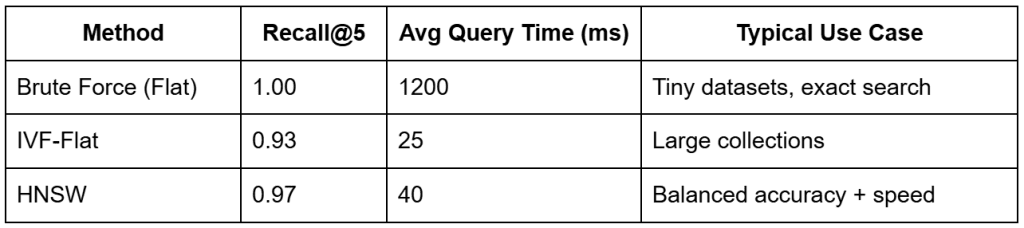

You’ll often see performance expressed using recall@k, the fraction of true neighbors recovered among the top-k results.

A good ANN index achieves 0.9 – 0.99 recall@k while being orders of magnitude faster than brute force.

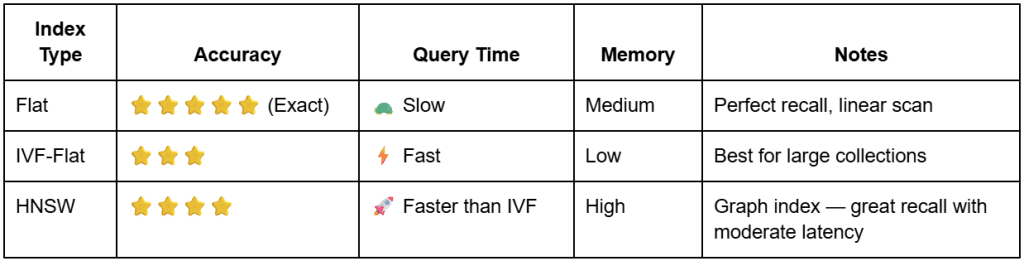

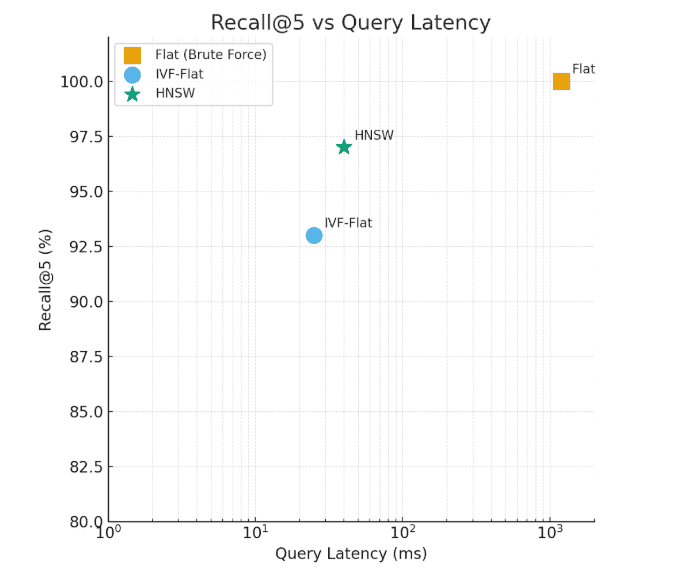

The Flat index delivers exact results but with high latency, whereas HNSW and IVF-Flat balance speed and accuracy for scalable retrieval.

What You’ll Learn Next

In the next section, we’ll open the black box and look inside FAISS — the industry-standard library that powers vector search at scale.

You’ll understand how these indexes (i.e., Flat, IVF, and HNSW) are built, what parameters control their trade-offs, and how to construct them yourself in code.

By the end, you’ll see how these algorithms let you scale semantic search from a few dozen vectors to millions — without loss of meaning.

Would you like immediate access to 3,457 images curated and labeled with hand gestures to train, explore, and experiment with … for free? Head over to Roboflow and get a free account to grab these hand gesture images.

Inside FAISS: How Vector Indexing Works

In Lesson 1, we learned how to generate embeddings and compute semantic similarity.

In Section 1 of this post, we discovered why brute-force search breaks down as our vector collection grows.

Now, let’s open the black box and explore how FAISS makes large-scale vector search practical.

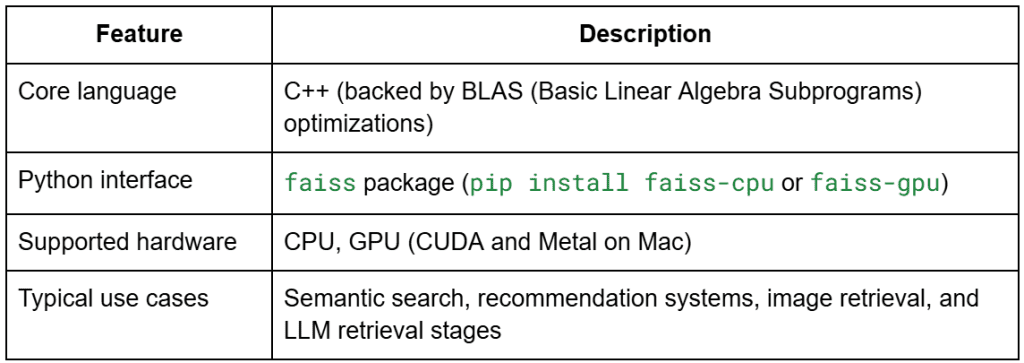

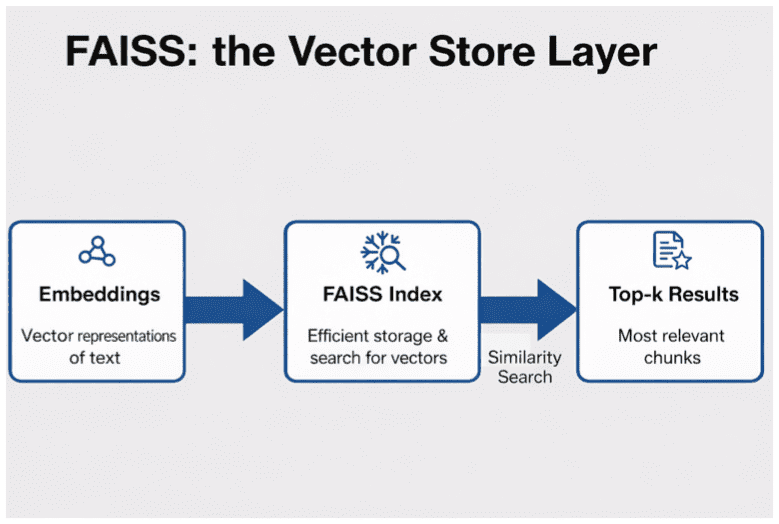

What Is FAISS?

FAISS (Facebook AI Similarity Search) is an open-source library developed by Meta AI for efficient similarity search and clustering of dense vectors.

It’s implemented in highly optimized C++ with Python bindings and optional GPU support.

In simple terms, FAISS is the NumPy of vector search — it provides a consistent interface for building, training, querying, and persisting vector indexes, with dozens of back-ends optimized for both accuracy and speed.

Why We Need Index Structures

Every FAISS index is a data structure that helps you locate nearest neighbors efficiently in a large vector space.

Instead of storing raw vectors in a flat array and scanning them linearly, FAISS builds one of several possible structures that act as “shortcuts” through the space.

Let’s explore the three we will implement in this tutorial — Flat, IVF-Flat, and HNSW — and see how each balances speed and accuracy.

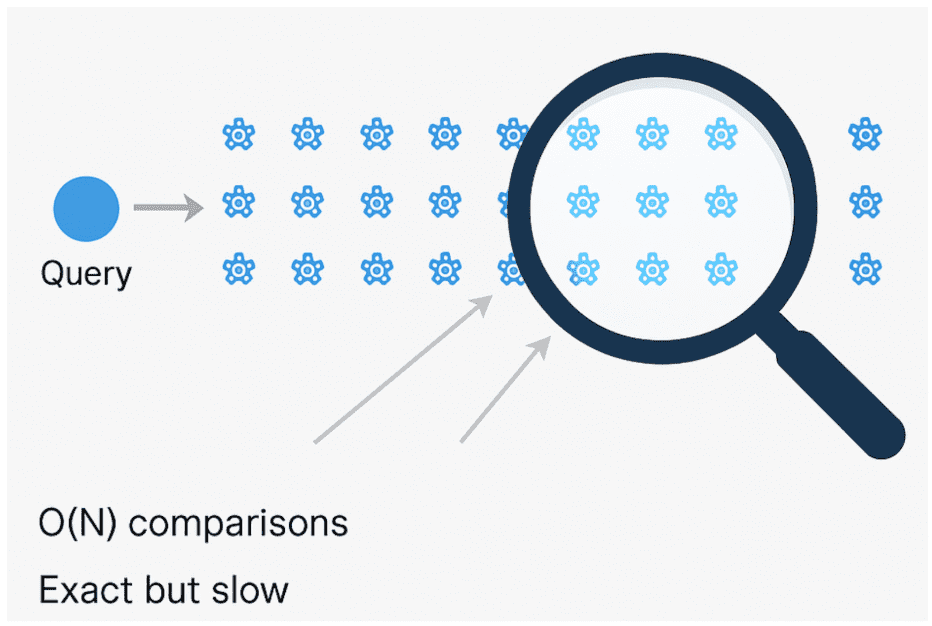

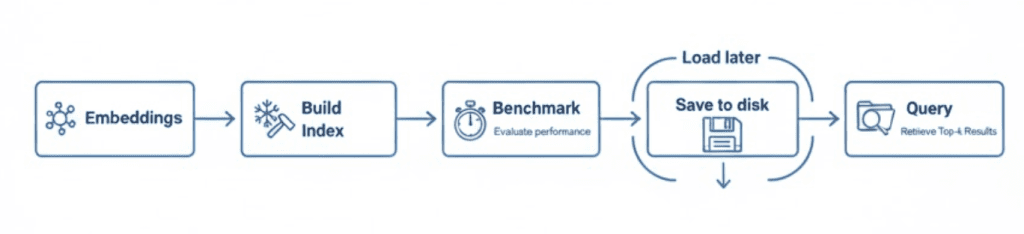

Flat Index: The Exact Baseline

The Flat index is the simplest and most precise approach.

It stores every embedding as is and computes cosine similarity (or inner product) between the query and each vector.

This is essentially our brute-force baseline from Lesson 1.

It achieves perfect recall (1.0) but scales poorly — every query requires scanning all vectors.

O(N) process that ensures exact matches but becomes prohibitively slow for large-scale datasets (source: image by the author).IVF-Flat: Coarse Clustering for Speed

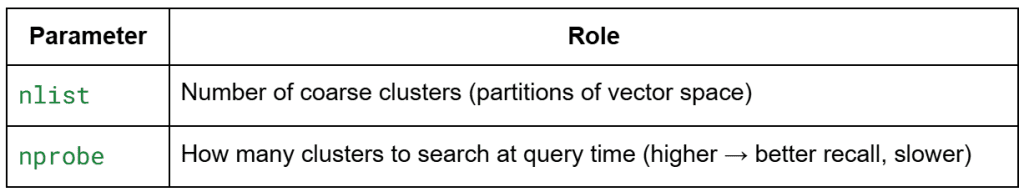

IVF stands for Inverted File Index.

The idea is simple but powerful: partition the vector space into coarse clusters and search only a few of them at query time.

Step-by-step:

- FAISS trains a coarse quantizer using k-means on your embeddings. Each cluster center is a “list” in the index — there are

nlistof them. - Each vector is assigned to its closest centroid.

- During search, instead of scanning all lists, FAISS only probes

nprobeof them (the most promising clusters).

That reduces search complexity from O(N) to roughly O(N / nlist × nprobe).

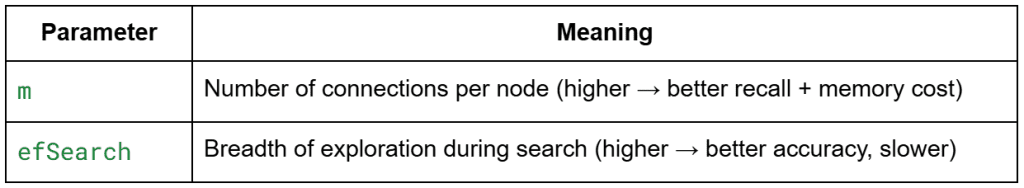

HNSW: Navigable Graph Search

The Hierarchical Navigable Small World (HNSW) index uses a graph instead of clusters.

Each embedding is a node connected to its nearest neighbors.

At query time, the algorithm navigates the graph — starting from a random entry point and greedily moving to closer nodes until it reaches a local minimum.

This search is then refined by probing nearby connections to find better candidates.

Intuition: It’s like finding a friend’s house by asking neighbors for directions instead of checking every street yourself.

Comparing the Three Index Types

What You’ll Do Next

Now that you understand what each index does, you’ll see how to implement them with FAISS.

In the next section, we’ll dive into the code — explaining config.py, vector_search_utils.py, then building and benchmarking indexes side by side.

Configuring Your Development Environment

To follow this guide, you’ll need to install several Python libraries for vector search and approximate nearest neighbor (ANN) indexing.

The core dependencies are:

$ pip install sentence-transformers==2.7.0 $ pip install faiss-cpu==1.8.0 $ pip install numpy==1.26.4 $ pip install rich==13.8.1

Note on FAISS Installation

- Use

faiss-cpufor CPU-only environments (most common) - If you have a CUDA-compatible GPU, you can install

faiss-gpuinstead for better performance with large datasets

Optional Dependencies

If you plan to extend the examples with your own experiments:

$ pip install matplotlib # For creating performance visualizations

Verifying Your Installation

You can verify FAISS is properly installed by running:

import faiss

print(f"FAISS version: {faiss.__version__}")

Need Help Configuring Your Development Environment?

All that said, are you:

- Short on time?

- Learning on your employer’s administratively locked system?

- Wanting to skip the hassle of fighting with the command line, package managers, and virtual environments?

- Ready to run the code immediately on your Windows, macOS, or Linux system?

Then join PyImageSearch University today!

Gain access to Jupyter Notebooks for this tutorial and other PyImageSearch guides pre-configured to run on Google Colab’s ecosystem right in your web browser! No installation required.

And best of all, these Jupyter Notebooks will run on Windows, macOS, and Linux!

Implementation Walkthrough

Alright, time to get our hands dirty.

You’ve seen why indexing matters and how FAISS structures (e.g., Flat, HNSW, and IVF) work conceptually; now we’ll implement them and run them side-by-side. We’ll build each index, query it with the same vectors, and compare recall@k, average query latency, build time, and a rough memory footprint.

To keep things clean, we’ll proceed in 3 parts:

- config: paths and constants

- FAISS utilities: builders, query/save/load, benchmarking helpers

- driver script: ties it all together and prints a clear, comparable report

pyimagesearch/config.py (what we use in Lesson 2)

These constants keep paths, filenames, and defaults in one place, so the rest of the code stays clean and portable.

from pathlib import Path

import os

# Base paths

BASE_DIR = Path(__file__).resolve().parent.parent

DATA_DIR = BASE_DIR / "data"

INPUT_DIR = DATA_DIR / "input"

OUTPUT_DIR = DATA_DIR / "output"

INDEX_DIR = DATA_DIR / "indexes"

FIGURES_DIR = DATA_DIR / "figures"

# Corpus files (allow environment overrides for flexibility)

_CORPUS_OVERRIDE = os.getenv("CORPUS_PATH")

_CORPUS_META_OVERRIDE = os.getenv("CORPUS_META_PATH")

CORPUS_PATH = Path(_CORPUS_OVERRIDE) if _CORPUS_OVERRIDE else INPUT_DIR / "corpus.txt"

CORPUS_META_PATH = Path(_CORPUS_META_OVERRIDE) if _CORPUS_META_OVERRIDE else INPUT_DIR / "corpus_metadata.json"

# Embedding artifacts

EMBEDDINGS_PATH = OUTPUT_DIR / "embeddings.npy"

METADATA_ALIGNED_PATH = OUTPUT_DIR / "metadata_aligned.json"

DIM_REDUCED_PATH = OUTPUT_DIR / "pca_2d.npy"

# Index artifacts

FLAT_INDEX_PATH = INDEX_DIR / "faiss_flat.index"

HNSW_INDEX_PATH = INDEX_DIR / "faiss_hnsw.index"

# Models & defaults

EMBED_MODEL_NAME = "sentence-transformers/all-MiniLM-L6-v2"

SEED = 42

DEFAULT_TOP_K = 5

SIM_THRESHOLD = 0.35 # not used in this lesson, but fine to keep

# Ensure dirs exist

for d in (OUTPUT_DIR, INDEX_DIR, FIGURES_DIR):

d.mkdir(parents=True, exist_ok=True)

What’s happening here (and why):

- We compute

BASE_DIRand derive data/ subfolders so the repo runs the same on any machine. CORPUS_PATHandCORPUS_META_PATHcan be overridden via environment variables — a nice quality-of-life touch if you swap datasets.EMBEDDINGS_PATHis the cache produced in Lesson 1; we load it here to avoid re-embedding.FLAT_INDEX_PATHandHNSW_INDEX_PATHare where we’ll persist FAISS indexes after benchmarking. (IVF can be added similarly if you want on-disk reuse.)- The directory loop at the bottom makes sure first runs never fail due to missing folders.

Note: The file also contains prompt-related constants for Lesson 3 (RAG). We don’t use them here — safe to ignore in this lesson.

pyimagesearch/vector_search_utils.py

This module is your FAISS “Swiss Army Knife.” We’ll go through every function you shared, including the ones you asked me not to miss: brute_force_search, measure_latency, and estimate_index_memory_bytes, plus query/save/load.

a) FAISS Import Guard

try:

import faiss # type: ignore

except ImportError:

faiss = None # type: ignore

def require_faiss():

if faiss is None:

raise ImportError("faiss not installed. Please pip install faiss-cpu (or faiss-gpu).")

This is a friendly safety check. Any time we build or query an index, we call require_faiss(). If FAISS isn’t installed, you get a clear error with the exact package to install.

b) Flat (exact) Index

def build_flat_index(embeddings: np.ndarray):

require_faiss()

d = embeddings.shape[1]

index = faiss.IndexFlatIP(d)

index.add(embeddings.astype(np.float32))

return index

What it does:

We create an IndexFlatIP, where IP = inner product. Because our embeddings are L2-normalized (from Lesson 1), inner product equals cosine similarity. We then .add() all vectors (as float32) to the index. This gives perfect recall but scans everything (slow at scale). This equivalence holds only if both stored embeddings and query vectors are L2-normalized. If not, inner product will not equal cosine similarity.

c) HNSW (graph) Index

def build_hnsw_index(embeddings: np.ndarray, m: int = 32, ef_construction: int = 128, ef_search: int = 64):

require_faiss()

d = embeddings.shape[1]

index = faiss.IndexHNSWFlat(d, m, faiss.METRIC_INNER_PRODUCT)

index.hnsw.efConstruction = ef_construction

index.hnsw.efSearch = ef_search

index.add(embeddings.astype(np.float32))

return index

What it does:

HNSW builds a multi-layer graph over your vectors:

m: sets connectivity per node (more links → better recall and higher memory)efConstruction: controls how widely we explore during graph buildingefSearch: controls breadth at query time (higher → better recall, slower)

We add vectors and return a ready-to-query graph index.

d) IVF-Flat (clustered) Index

def build_ivf_flat_index(embeddings: np.ndarray, nlist: int = 8, nprobe: int = 4):

require_faiss()

d = embeddings.shape[1]

quantizer = faiss.IndexFlatIP(d)

index = faiss.IndexIVFFlat(quantizer, d, nlist, faiss.METRIC_INNER_PRODUCT)

if not index.is_trained:

index.train(embeddings.astype(np.float32))

index.add(embeddings.astype(np.float32))

index.nprobe = nprobe

return index

What it does:

IVF partitions your space into nlist coarse clusters (centroids via k-means). You must train first, then add vectors. Queries only probe a handful of lists (nprobe) near the query, drastically reducing the number of distance comparisons.

- Tune

nlistup as your dataset grows (more clusters). - Tune

nprobefor recall vs. latency.

e) Unified Query Wrapper

def query_index(index, query_vectors: np.ndarray, top_k: int = config.DEFAULT_TOP_K) -> Tuple[np.ndarray, np.ndarray]:

distances, indices = index.search(query_vectors.astype(np.float32), top_k)

return indices, distances

What it does:

FAISS returns (distances, indices), but most of our code wants (indices, distances). This wrapper normalizes that behavior and ensures the input dtype is float32. Use this anywhere you want a consistent top-k interface.

f) Save and Load Indexes

def save_index(index, path: Path):

require_faiss()

faiss.write_index(index, str(path))

def load_index(path: Path):

require_faiss()

return faiss.read_index(str(path))

What it does:

Build once, reuse many times. These functions serialize an index to disk and read it back instantly — essential when your dataset is large or when you run repeated experiments.

g) Brute-Force Baseline (ground truth)

def brute_force_search(embeddings: np.ndarray, queries: np.ndarray, top_k: int) -> Tuple[np.ndarray, np.ndarray]:

sims = queries @ embeddings.T # cosine if normalized

top_indices = np.argsort(-sims, axis=1)[:, :top_k]

top_scores = np.take_along_axis(sims, top_indices, axis=1)

return top_indices, top_scores

What it does:

This computes exact cosine similarities (via matrix multiplication) and sorts them to get the true top-k. We use this to measure recall@k of ANN indexes.

h) Latency measurement helper

def measure_latency(func, *args, repeat: int = 3, **kwargs) -> Dict[str, Any]:

import time

times = []

for _ in range(repeat):

start = time.perf_counter()

func(*args, **kwargs)

times.append(time.perf_counter() - start)

return {"avg_s": float(np.mean(times)), "stdev_s": float(np.std(times)), "runs": times}

What it does:

This runs the same query callable a few times and returns the average and standard deviation. This gives stable latency numbers for fair comparisons between Flat, HNSW, and IVF.

i) Rough Memory Estimator (educational)

def estimate_index_memory_bytes(index_type: str, n: int, d: int, m: int = 32, nlist: int = 0) -> int:

base = n * d * 4

if index_type == "Flat":

return base

if index_type == "HNSW":

return base + n * m * 4

if index_type == "IVF-Flat":

return base + nlist * d * 4

return base

What it does:

Provides a lower-bound estimate (in bytes) for apples-to-apples reporting.

- Flat: just the raw vectors (

float32= 4 bytes). - HNSW: vectors + approximate link list.

- IVF-Flat: vectors + centroid matrix.

FAISS has internal overhead, so treat this as a teaching aid, not an exact profiler.

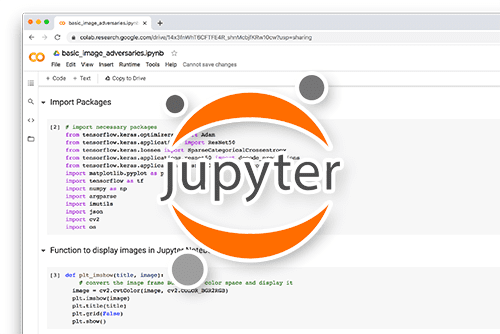

02_vector_search_ann.py (driver)

This script glues everything together:

- loads embeddings

- builds indexes

- benchmarks recall and latency

- displays results

- persists indexes

a) Ensuring Embeddings Exist

def ensure_embeddings():

if config.EMBEDDINGS_PATH.exists():

emb, meta = load_embeddings()

texts, _ = load_corpus()

return emb, meta, texts

texts, meta = load_corpus()

model = get_model()

emb = generate_embeddings(texts, model=model)

from pyimagesearch.embeddings_utils import save_embeddings

save_embeddings(emb, meta)

return emb, meta, texts

First run? We load corpus → embed → save. Subsequent runs? We simply load embeddings.npy. This keeps the ANN lesson focused on indexing rather than recomputing vectors.

b) Query Sampling and Recall

def sample_query_indices(n: int, total: int, seed: int = config.SEED) -> np.ndarray:

rng = np.random.default_rng(seed)

return rng.choice(total, size=min(n, total), replace=False)

def compute_recall(brute_force_idx: np.ndarray, ann_idx: np.ndarray) -> float:

matches = 0

total = brute_force_idx.shape[0] * brute_force_idx.shape[1]

for row_true, row_test in zip(brute_force_idx, ann_idx):

matches += len(set(row_true.tolist()) & set(row_test.tolist()))

return matches / total if total else 0.0

We pick some random query rows from the embedding matrix and compare ANN results against the ground truth to compute recall@k.

c) Benchmark Core

def benchmark(

embeddings: np.ndarray,

queries: np.ndarray,

k: int = config.DEFAULT_TOP_K,

hnsw_m: int = 32,

hnsw_ef_search: int = 64,

ivf_nlist: int = 8,

ivf_nprobe: int = 4,

auto_adjust_ivf: bool = True,

):

# 1) Ground truth

bf_idx, bf_scores = brute_force_search(embeddings, queries, k)

results = []

# 2) Flat

build_start = time.perf_counter()

flat_index = build_flat_index(embeddings)

build_time_flat = time.perf_counter() - build_start

flat_index.search(queries[:1].astype(np.float32), k) # warm-up

latency_flat = measure_latency(flat_index.search, queries.astype(np.float32), k)

flat_dist, flat_idx_res = flat_index.search(queries.astype(np.float32), k)

recall_flat = compute_recall(bf_idx, flat_idx_res)

if recall_flat < 0.99:

print(f"[red]Warning: Flat recall {recall_flat:.3f} < 0.99. Check normalization or brute force implementation.[/red]")

results.append(("Flat", recall_flat, latency_flat["avg_s"], build_time_flat,

estimate_index_memory_bytes("Flat", embeddings.shape[0], embeddings.shape[1])))

# 3) HNSW

try:

build_start = time.perf_counter()

hnsw_index = build_hnsw_index(embeddings, m=hnsw_m, ef_search=hnsw_ef_search)

build_time_hnsw = time.perf_counter() - build_start

hnsw_index.search(queries[:1].astype(np.float32), k)

latency_hnsw = measure_latency(hnsw_index.search, queries.astype(np.float32), k)

hnsw_dist, hnsw_idx_res = hnsw_index.search(queries.astype(np.float32), k)

recall_hnsw = compute_recall(bf_idx, hnsw_idx_res)

results.append(("HNSW", recall_hnsw, latency_hnsw["avg_s"], build_time_hnsw,

estimate_index_memory_bytes("HNSW", embeddings.shape[0], embeddings.shape[1], m=hnsw_m)))

except Exception as e:

results.append(("HNSW (unavailable)", 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0))

print(f"[yellow]HNSW build failed: {e}[/yellow]")

# 4) IVF-Flat (+ tiny-corpus auto-tuning)

try:

effective_nlist = ivf_nlist

if auto_adjust_ivf:

N = embeddings.shape[0]

if N < ivf_nlist * 5:

shrunk = max(2, min(ivf_nlist, max(2, N // 2)))

if shrunk != ivf_nlist:

print(f"[yellow]Adjusting nlist from {ivf_nlist} to {shrunk} for tiny corpus (N={N}).[/yellow]")

effective_nlist = shrunk

build_start = time.perf_counter()

ivf_index = build_ivf_flat_index(embeddings, nlist=effective_nlist, nprobe=ivf_nprobe)

build_time_ivf = time.perf_counter() - build_start

ivf_index.search(queries[:1].astype(np.float32), k)

latency_ivf = measure_latency(ivf_index.search, queries.astype(np.float32), k)

ivf_dist, ivf_idx_res = ivf_index.search(queries.astype(np.float32), k)

recall_ivf = compute_recall(bf_idx, ivf_idx_res)

results.append(("IVF-Flat", recall_ivf, latency_ivf["avg_s"], build_time_ivf,

estimate_index_memory_bytes("IVF-Flat", embeddings.shape[0], embeddings.shape[1], nlist=effective_nlist)))

except Exception as e:

results.append(("IVF-Flat (failed)", 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0))

print(f"[yellow]IVF build failed: {e}[/yellow]")

return bf_idx, results

The pipeline is:

- create a ground-truth baseline

- build each index

- warm up

- measure latency

- compute recall vs. the ground-truth baseline

- record a row of metrics

The IVF block also includes a tiny-corpus auto-adjust so you don’t “over-partition” small datasets.

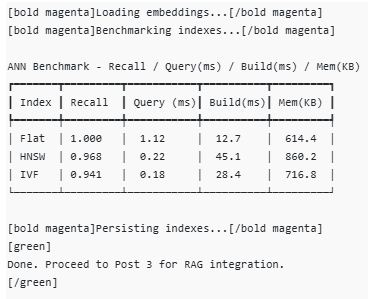

d) Results Table

def display_results(results):

table = Table(title="ANN Benchmark - Recall / Query(ms) / Build(ms) / Mem(KB)")

table.add_column("Index")

table.add_column("Recall", justify="right")

table.add_column("Query (ms)", justify="right")

table.add_column("Build (ms)", justify="right")

table.add_column("Mem (KB)", justify="right")

for name, recall, q_latency, build_time, mem_bytes in results:

table.add_row(

name,

f"{recall:.3f}",

f"{q_latency*1000:.2f}",

f"{build_time*1000:.1f}",

f"{mem_bytes/1024:.1f}",

)

print(table)

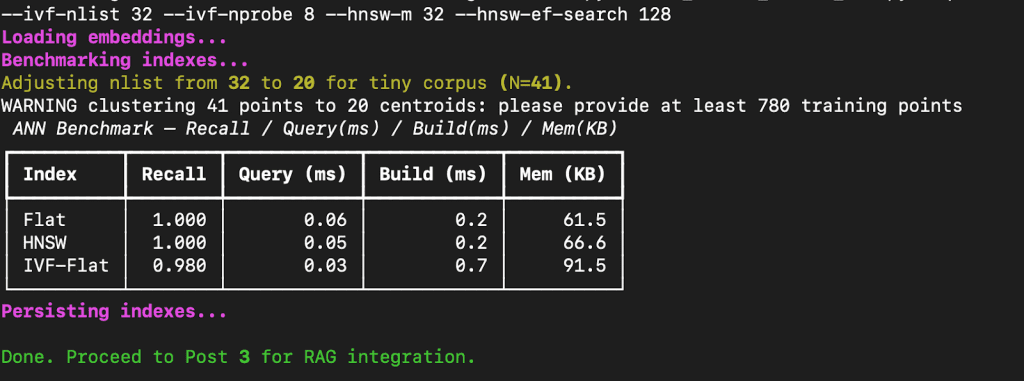

This produces the clean terminal table you’ve seen earlier — great for screenshots.

e) Persisting Indexes

def persist_indexes(embeddings: np.ndarray):

from pyimagesearch.vector_search_utils import save_index, build_flat_index

flat = build_flat_index(embeddings)

save_index(flat, config.FLAT_INDEX_PATH)

try:

from pyimagesearch.vector_search_utils import build_hnsw_index

hnsw = build_hnsw_index(embeddings)

save_index(hnsw, config.HNSW_INDEX_PATH)

except Exception:

pass

We persist Flat and HNSW by default, so Lesson 3 can load them directly. (Add IVF persistence if you want — same pattern.)

f) CLI Entrypoint

def main():

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser(description="ANN benchmark demo")

parser.add_argument("--k", type=int, default=5)

parser.add_argument("--queries", type=int, default=5)

parser.add_argument("--hnsw-m", type=int, default=32)

parser.add_argument("--hnsw-ef-search", type=int, default=64)

parser.add_argument("--ivf-nlist", type=int, default=8)

parser.add_argument("--ivf-nprobe", type=int, default=4)

parser.add_argument("--no-auto-adjust-ivf", action="store_true")

args = parser.parse_args()

print("[bold magenta]Loading embeddings...[/bold magenta]")

embeddings, metadata, texts = ensure_embeddings()

q_idx = sample_query_indices(args.queries, embeddings.shape[0])

queries = embeddings[q_idx]

print("[bold magenta]Benchmarking indexes...[/bold magenta]")

bf_idx, results = benchmark(

embeddings,

queries,

k=args.k,

hnsw_m=args.hnsw_m,

hnsw_ef_search=args.hnsw_ef_search,

ivf_nlist=args.ivf_nlist,

ivf_nprobe=args.ivf_nprobe,

auto_adjust_ivf=not args.no_auto_adjust_ivf,

)

display_results(results)

print("[bold magenta]Persisting indexes...[/bold magenta]")

persist_indexes(embeddings)

print("[green]nDone. Proceed to Post 3 for RAG integration.n[/green]")

Run it like this:

python 02_vector_search_ann.py --queries 10 --k 5 --ivf-nlist 32 --ivf-nprobe 8 --hnsw-m 32 --hnsw-ef-search 128

Terminal Output (example)

Benchmarking and Analyzing Results

After running the script with:

python 02_vector_search_ann.py --queries 10 --k 5 --ivf-nlist 32 --ivf-nprobe 8 --hnsw-m 32 --hnsw-ef-search 128

FAISS prints a benchmark table comparing Flat, HNSW, and IVF-Flat across recall, query latency, build time, and memory footprint.

How to Interpret These Results

Let’s break down what this means.

- Flat Index:

This performs an exact nearest-neighbor search. Every query compares against all stored embeddings. It gives perfect recall (1.0) but becomes slow at scale because it’s linear in the number of vectors. - HNSW (Hierarchical Navigable Small World):

A graph-based index that builds layered shortcuts between points. It maintains near-perfect recall while cutting down query latency by 10-50× on large datasets.

Here, because our dataset is tiny (41 vectors), the difference isn’t dramatic — but with 1M+ vectors, HNSW scales gracefully. - IVF-Flat (Inverted File Index):

This structure first clusters vectors into “lists” (centroids), then searches only a few clusters (nprobe).

You can see a small recall drop (0.98) because some true neighbors fall outside probed clusters — but query speed improves noticeably.

The build time is slightly higher since training the quantizer (k-means step) adds overhead.

Takeaways

- For small datasets, Flat is perfectly fine — it’s fast and exact.

- For large-scale retrieval (e.g., thousands of documents), HNSW offers the best accuracy — latency balance.

- For ultra-large datasets with millions of vectors, IVF-Flat or IVF-PQ can drastically cut memory and latency with minimal recall loss.

- Always benchmark with your actual data — FAISS lets you trade off accuracy and performance based on your use case.

What’s next? We recommend PyImageSearch University.

86+ total classes • 115+ hours hours of on-demand code walkthrough videos • Last updated: February 2026

★★★★★ 4.84 (128 Ratings) • 16,000+ Students Enrolled

I strongly believe that if you had the right teacher you could master computer vision and deep learning.

Do you think learning computer vision and deep learning has to be time-consuming, overwhelming, and complicated? Or has to involve complex mathematics and equations? Or requires a degree in computer science?

That’s not the case.

All you need to master computer vision and deep learning is for someone to explain things to you in simple, intuitive terms. And that’s exactly what I do. My mission is to change education and how complex Artificial Intelligence topics are taught.

If you’re serious about learning computer vision, your next stop should be PyImageSearch University, the most comprehensive computer vision, deep learning, and OpenCV course online today. Here you’ll learn how to successfully and confidently apply computer vision to your work, research, and projects. Join me in computer vision mastery.

Inside PyImageSearch University you’ll find:

- ✓ 86+ courses on essential computer vision, deep learning, and OpenCV topics

- ✓ 86 Certificates of Completion

- ✓ 115+ hours hours of on-demand video

- ✓ Brand new courses released regularly, ensuring you can keep up with state-of-the-art techniques

- ✓ Pre-configured Jupyter Notebooks in Google Colab

- ✓ Run all code examples in your web browser — works on Windows, macOS, and Linux (no dev environment configuration required!)

- ✓ Access to centralized code repos for all 540+ tutorials on PyImageSearch

- ✓ Easy one-click downloads for code, datasets, pre-trained models, etc.

- ✓ Access on mobile, laptop, desktop, etc.

Summary

In this tutorial, you moved beyond understanding embeddings and stepped into the practical world of vector search. You began by revisiting the limitations of brute-force similarity search and saw why indexing is crucial when datasets grow larger. Then, you explored how FAISS, Meta’s open-source library for efficient similarity search, builds the backbone of modern vector databases.

From there, you implemented and compared 3 major index types (i.e., Flat, HNSW, and IVF-Flat) each offering a different trade-off between speed, recall, and memory. You wrote code to benchmark their performance, measuring recall@k, query latency, build time, and memory usage, and visualized the results directly in your terminal. Along the way, you saw how HNSW maintains near-perfect accuracy while drastically improving query speed, and how IVF-Flat compresses the search space to achieve sub-millisecond responses even with slight precision loss.

By the end, you not only understood how approximate nearest neighbor (ANN) search works but also saw why it matters — enabling scalable, real-time retrieval without compromising too much on accuracy. You also saved your indexes, preparing them for use in the next lesson, where we’ll connect them to a Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) pipeline and bring everything full circle: embeddings, vector search, and large language models working together in action.

Citation Information

Singh, V. “Vector Search with FAISS: Approximate Nearest Neighbor (ANN) Explained,” PyImageSearch, P. Chugh, S. Huot, A. Sharma, and P. Thakur, eds., 2026, https://pyimg.co/htl5f

@incollection{Singh_2026_vector-search-with-faiss-ann-explained,

author = {Vikram Singh},

title = {{Vector Search with FAISS: Approximate Nearest Neighbor (ANN) Explained}},

booktitle = {PyImageSearch},

editor = {Puneet Chugh and Susan Huot and Aditya Sharma and Piyush Thakur},

year = {2026},

url = {https://pyimg.co/htl5f},

}

To download the source code to this post (and be notified when future tutorials are published here on PyImageSearch), simply enter your email address in the form below!

Download the Source Code and FREE 17-page Resource Guide

Enter your email address below to get a .zip of the code and a FREE 17-page Resource Guide on Computer Vision, OpenCV, and Deep Learning. Inside you’ll find my hand-picked tutorials, books, courses, and libraries to help you master CV and DL!

The post Vector Search with FAISS: Approximate Nearest Neighbor (ANN) Explained appeared first on PyImageSearch.