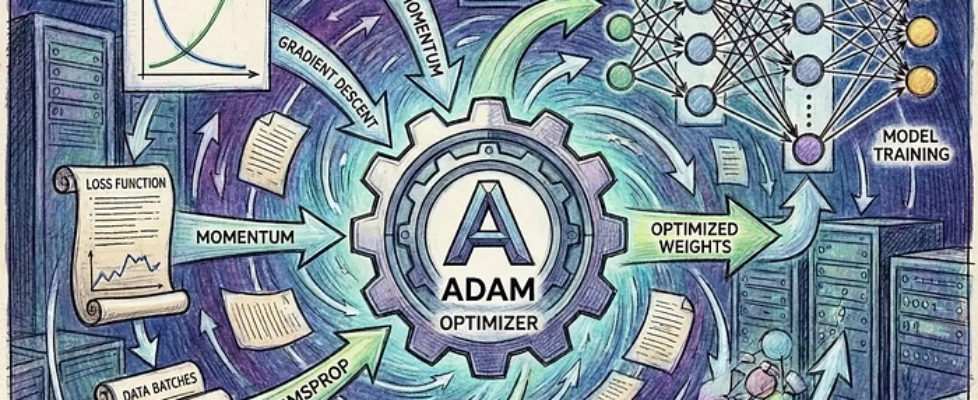

Unlocking the Magic of Adam: The Math Behind Deep Learning’s Favorite Optimizer

Author(s): Raaja Selvanaathan DATCHANAMOURTHY Originally published on Towards AI. Source: Author At the heart of every deep learning model lies a simple goal: minimizing error. We measure this error using something called a cost Function (or objective function). But knowing the error isn’t enough; the model needs a way to learn from it and improve over time. This is where optimization algorithms come in; they guide the model to update its internal parameters to get better results. Among the many algorithms available, one stands out as the absolute ‘star’ of the industry due to its efficiency and effectiveness: the Adam optimizer. In almost all projects we use the Adam optimizer. 1. Do you contemplate, why this specific algorithm is the star of the objective function optimizers in deep learning? 2. Have you wondered how this algorithm works? 3. Are you interested in learning the mathematical magic behind this algorithm? If you would like to have answers for one of the questions above, then this article is for you. This article heavily discusses the math behind the algorithm, and it is assumed that you are familiar with statistics, linear algebra and calculus. 1. Why Adam? In traditional ML models we use the well-known gradient descent optimizers, specifically the stochastic one, to generalize our model. This works well and is a go-to for most of the ML projects. But deep learning poses a different challenge.1️⃣In deep learning we usually work with massive volumes of data, and we usually train them as batches instead of the whole volume. Splitting them into mini batches while training and then optimizing them introduce uncertainty in the optimization. In other words, the optimization process became stochastic or introduced variations from batch to batch.This is exactly due to the fact that some batches contain samples that give large gradients, and some might give smaller gradients. You can guess that this is exactly similar scenario of exploding and vanishing gradients. So, the gradients introduce the random process; this is the main problem that Adam solves. 2️⃣Another important problem with the neural network architecture is the shape of the cost function. If you are familiar with optimization and conditions for the optimality, the cost function should be a convex function or a bowl-shaped function to work with optimization algorithms like stochastic gradient descent.But due to the nested architecture of neural networks. the non-linearity introduced in the layers makes the cost function non-convex. So, our usual optimization functions cannot be used. Adam solves this; it addresses the problem as a non-convex optimization problem and uses statistics to solve this.Apart from this, it is invariant to gradient scaling, requires less memory, and is computationally efficient.Next we discuss a few important prerequisites to understand the algorithm. If you are familiar with concepts of moving averages and variances and exponential moving averages and variances, you can skip the sections 2 and 3. 2. Exponential moving average: The simple moving average method, which is different from the exponential moving average method we are about to discuss, uses a window to find the moving averages in consecutive data points. An example calculation is given below for a window size of 3. Source: Author As you can notice, it gives equal weight to the observations in a window. Now let us discuss the exponential moving average method and how efficient it is compared to the simple moving average method. The exponential moving average, or EMA, uses the average from the previous step and the observation in the current step to efficiently calculate the moving average. The formula is given below. Source: Author In the simple moving average, or SMA, method, we use a window of a particular size to control how much of the old observations can be used to influence our average. But in the EMA method we control this using the decay factor. If the decay factor is less, old observations quickly move out from the window and have less influence in our moving average, and vice versa. There are few important benefits of using EMA over SMA:1️⃣ Unlike SMA, which needs to have all the observations of the window in memory, EMA just requires the EMA from the previous step; hence it is memory efficient and the computation complexity is O(1). Due to these reasons, EMA outperforms SMA.2️⃣EMA is extremely sensitive to recent observations. As the older observations decay, the newer observations have more weight in EMA, hence; if we have a drastic change in the observation, it is quicker to spot them in EMA. But in SMA, as the observations are given equal weights, there is a hard delay to find immediate changes in observations. An example plot is given below. Source: Author As you can see in the first plot, the magnitude of the observations are almost similar. But in the second plot there is a change in magnitude for the observations in the middle. If we use the SMA, the 3rd window cannot identify this drastic change in the magnitude. But if we use EMA, the change can be detected as soon as you start moving to the observation in the middle. The previous EMA will be lower, and the current EMA will be higher. 3. Exponential moving variance: Exponential moving variance is similar to the Exponential moving average, where we control the influence of the spread from the old observations using the decay factor. The formula for EMV is given below. Source: Author Here, we square the current observation to avoid cancellations of the negative observation with the positive one. Also, it explodes the larger number, and so any drastic change in the spread of the observations is quickly identified by EMV.The EMV, however, produces the uncentered variance. In regular variance calculation we subtract the mean of the observations to center them. If we center our observations before calculating the EMV, then the EMV would lose the ability to quickly react to sudden variance changes. In other words, we must maintain our magnitude of the observation. Consider the below […]