The Rise of Synthetic Labor

Why the Next Workforce Is Not Human or Robotic but Agentic

Abstract

Advanced economies are entering a sustained structural labor deficit driven by demographic decline, aging populations, and persistent sector-specific shortages. Traditional automation, including robotic process automation and narrow task-based systems, has delivered productivity improvements but has proven insufficient to address this gap at scale.

This paper introduces synthetic labor, defined as agentic artificial intelligence systems that perform economically productive work with context awareness, memory, planning, tool use, coordination, and governance. Unlike conventional automation, synthetic labor operates as a new class of software-defined workers embedded directly within organizational workflows.

We argue that synthetic labor represents the next labor class of the Intelligence Age. We outline its technical architecture, economic implications, and the strategic requirements enterprises must address between 2026 and 2035.

1. Introduction

Every major economic era has introduced a new way of organizing productive labor.

The Agricultural Age scaled human effort through land and muscle. The Industrial Age mechanized physical work through machines. The Information Age digitized coordination, computation, and communication. The Intelligence Age is now introducing a fourth labor class: synthetic labor.

Synthetic labor is not automation, chatbots, or robotic process automation. It is a governed, agentic workforce capable of interpreting context, making bounded decisions, executing workflows end-to-end, and coordinating with other agents without continuous human supervision.

This transition is driven by structural forces rather than discretionary choice. Demographic decline, shrinking labor pools, and rising productivity demands are forcing enterprises to expand output without expanding headcount. Synthetic labor is moving from experimental capability to economic necessity. Just as industrial machinery reshaped the 19th century, synthetic labor will reshape the 21st by redefining how organizations produce value, structure work, and compete across every major sector.

2. The Structural Labor Problem

Advanced economies face structural labor constraints, and multiple critical sectors are already experiencing persistent shortages. Global fertility rates have fallen sharply over the past several decades. Data from Our World in Data shows that the global total fertility rate declined from over five children per woman in 1950 to roughly 2.3 in 2023, with most developed economies well below the replacement threshold of 2.1. [1] In the United States, projections from the Congressional Budget Office indicate that growth in the native‑born working‑age population will remain near zero through the 2030s, meaning labor force expansion depends almost entirely on immigration, which itself faces political and institutional constraints. [2]

Sector‑level data shows the same pattern. The Manufacturing Institute and Deloitte estimate that United States manufacturers will require up to 3.8 million additional workers by 2033, with roughly half of those roles at risk of remaining unfilled. [3] The Association of American Medical Colleges projects a physician shortage of up to 86,000 by 2036. [4] Energy, logistics, and infrastructure operators report similar gaps, driven by retirements, aging workforces, and insufficient numbers of new entrants. [5]

These forces combine into a demographic and skills cliff that no amount of hiring, outsourcing, or incremental automation can bridge. This is the structural context in which synthetic labor emerges as an economic necessity. They expose the limits of traditional automation.

3. Why Traditional Automation Is Insufficient

For decades, organizations relied on scripts, macros, and robotic process automation to squeeze efficiency out of existing workflows. These tools delivered value, but they exposed structural limits. Rule‑based automation is brittle and breaks when interfaces, data formats, or business rules shift. It cannot plan or adapt across uncertain, multi‑step workflows, and it remains narrowly task‑focused rather than capable of managing end‑to‑end processes. As a result, enterprises continue to depend on human intermediaries to bridge brittle systems, interpret exceptions, and manage edge cases that traditional automation cannot address.

Industry analyses reinforce this pattern. A significant share of robotic process automation initiatives fail to meet expectations or stall during scaling, with surveys from Deloitte and Ernst & Young frequently citing failure or underperformance rates approaching fifty percent for early‑stage deployments. [6] As labor constraints intensify, organizations require systems that can reason, adapt, and coordinate, instead of tools that simply execute predefined instructions. Synthetic labor is designed to fill those gaps.

4. Synthetic Labor Defined

Synthetic labor is a new labor class that refers to agentic systems capable of performing economically valuable work with limited or no continuous human supervision. The emphasis on economic value is essential as it distinguishes synthetic labor from simple automation or AI features. A synthetic labor unit must be able to carry out a workflow, produce a meaningful outcome, and generate measurable value in a way that substitutes for or augments human labor. Systems that cannot meet this threshold are better understood as software tools.

A synthetic labor unit behaves less like a script and more like a digital worker embedded directly into an enterprise. It absorbs real‑time context from the environment, carries forward memory and state across tasks, plans multi‑step actions, and executes them through secure system interfaces. It collaborates with other agents when work requires coordination, exposes its internal reasoning through observability and telemetry, and operates inside governance rails that enforce identity, access, logging, and escalation. All of these capabilities function together as an integrated system rather than isolated features.

Research on advanced AI agents consistently emphasizes that planning, memory, and contextual grounding are prerequisites for sustained autonomous behavior. [7] Enterprise guidance from firms such as IBM highlights that agentic systems must be observable, auditable, and controllable to operate safely at scale. To understand how synthetic labor operates, we must examine its architecture.

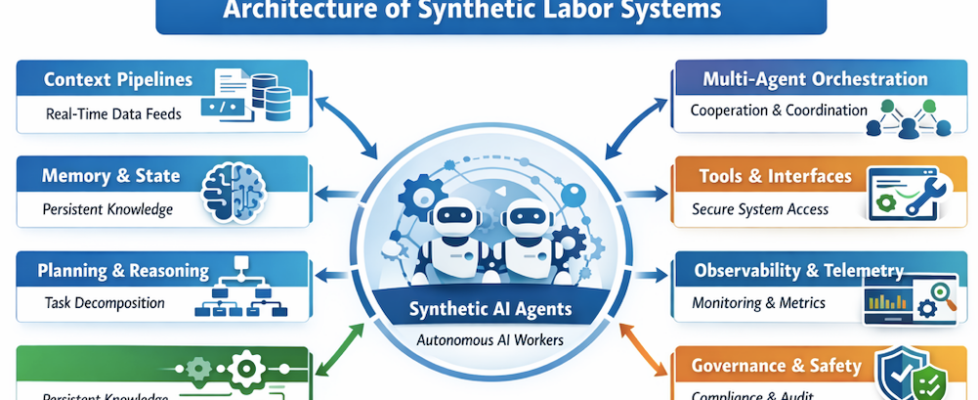

5. Architecture of Synthetic Labor Systems

Across both research literature and production deployments, seven technical pillars consistently define synthetic labor systems:

- Context pipelines that stream and canonicalize inputs for agents.

- Memory and state management that stores knowledge across sessions.

- Planning and reasoning engines that support hierarchical task decomposition.

- Multi‑agent orchestration that allocates work, coordinates tasks, and resolves conflicts.

- Tooling and secure interfaces that allow safe side effects in enterprise systems.

- Observability and telemetry that provide end‑to‑end tracing, metrics, logs, and dashboards to monitor agent behavior, detect drift, and quantify business impact.

- Governance and safety rails that record provenance, enforce policies, and enable audits.

The McKinsey Global Institute emphasizes that the economic value of agentic AI depends on redesigning workflows rather than simply adding AI features to existing systems. This architecture clearly differentiates synthetic labor platforms from consumer-facing AI applications.

6. Economic Impact from 2026 to 2035

Synthetic labor is emerging at a moment when labor scarcity and productivity pressure intersect.

First, labor shortages will intensify across healthcare, manufacturing, logistics, and energy as retirements outpace new entrants.

Second, productivity becomes the primary growth lever. Economic output is a function of labor input multiplied by productivity. When labor supply stagnates, productivity must increase to sustain growth. McKinsey estimates that agentic AI and advanced automation could technically address a substantial share of current work hours if fully implemented, hence it is one of the largest productivity opportunities in decades.[9]

Third, agents are already moving beyond browser-based environments. Warehouses, factories, hospitals, and energy grids deploy AI-driven decision systems at scale. Amazon has reported operating over one million robots coordinated by AI systems within its fulfillment network.[10]

Finally, regulatory and compliance pressures are accelerating the emergence of AgentOps as a distinct discipline focused on deploying, monitoring, auditing, and governing agentic systems at scale.[8]

7. Strategic Implications for Enterprises

Organizations that adopt synthetic labor intentionally can build durable competitive advantages, such as:

- Cost leverage: Synthetic labor scales horizontally with low marginal cost once validated.

- Operational resilience: Agentic systems provide operational continuity without fatigue or turnover. You can be confident that Agents do not quit, burn out, or churn.

- Speed: Agents operate with sub-second decision cycles, making their continuous execution faster than human-only workflows.

- Compliance by design: Governance can be embedded directly into agents’ workflows/architectures, thereby enabling compliance by design.

- Competitive advantage: Early investment in AgentOps and data infrastructure establishes durable advantages, similar to early cloud adoption in the late 2000s.

However, poorly governed agents will introduce operational, legal, and reputational risk. Successful adoption requires disciplined engineering practices, strong security controls, and explicit human oversight mechanisms.[11]

8. Practical Roadmap: What Companies Must Do Now

- Build an AgentOps function that integrates SRE, security, compliance, data engineering, and product management. As DevOps became essential in the 2010s, AgentOps will become essential in the 2020s.

- Redesign workflows for synthetic labor by decomposing Human workflows into agent-compatible loops(workflows). Start with a single high‑value workflow that is repetitive, rules‑based, and auditable, and validate an agentic pilot in that environment.

- Invest in context-engineering: instrument streams, canonical event models, and a memory store that agents can query. Agents are only as effective as the data they receive.

- Implement governance early through decision logs, agent identities, escalation paths, and periodic external review. Regulation is coming, and early movers will benefit.

- Reskill staff into agent supervisors, AgentOps engineers, and ethical auditors. These roles monitor agent behavior, enforce safety, and ensure alignment with human values.

Start with focused pilots, demonstrate measurable value, and scale deliberately. Each implementation builds institutional competence and establishes the foundation for broader agentic transformation.

9. Conclusion: The Future of Work Is Synthetic

Synthetic labor marks a structural shift in how work is organized and executed. Demographic pressures and sector‑specific shortages are making agentic systems not only attractive but increasingly necessary.

As advances in context engineering, memory, planning, and governance mature, synthetic labor will become one of the defining economic forces of the Intelligence Age.

Organizations that treat agentic systems as governed and engineered labor, rather than experimental features, will shape the next frontier of productivity, competitiveness, and economic power. This trajectory mirrors the pattern seen in prior technological shifts, where early adopters shaped industry standards and long‑term competitive dynamics. The institutions that learn to integrate synthetic labor effectively will define the competitive landscape of the coming decade.

References

- Our World in Data. Fertility Rate. https://ourworldindata.org/fertility-rate

- Congressional Budget Office. Demographic Outlook 2024 to 2054. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/61390

- Deloitte and The Manufacturing Institute. Manufacturing Workforce Study. https://themanufacturinginstitute.org/manufacturers-need-as-many-as-3-8-million-new-employees-by-2033

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Projected Physician Shortages. https://www.aamc.org/news/press-releases/new-aamc-report-shows-continuing-projected-physician-shortage

- International Energy Agency. World Energy Employment Report. https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-employment-2025

- UiPath. Why RPA Deployments Fail. https://www.uipath.com/blog/rpa/why-rpa-deployments-fail

- Prajna AI. Inside the Agent’s Mind. https://prajnaaiwisdom.medium.com/inside-the-agents-mind-how-ai-agents-decide-what-to-do-next-392e2d8672c5

- McKinsey Global Institute. Agents, Robots, and Us. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/technology-media-and-telecommunications/our-insights/agents-robots-and-us-skill-partnerships-in-the-age-of-ai

- Amazon. One Million Robots Announcement. https://www.aboutamazon.com/news/operations/amazon-million-robots-ai-foundation-model

- IBM. What Is AgentOps. https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/agentops

- ISACA. Auditing Agentic AI. https://www.isaca.org/resources/news-and-trends/industry-news/2025/the-growing-challenge-of-auditing-agentic-ai

The Rise of Synthetic Labor was originally published in Towards AI on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.