The Journey of Backpropagation in Neural Networks

Neural Networks have always been held as a very useful system in prediction analysis, recommendation engines, modeling and a lot more; it is because has the ability to extract complex patterns and relationships between the input and output data. This is because of the numerous layers of neural networks, that make the machine learning ‘deep’.

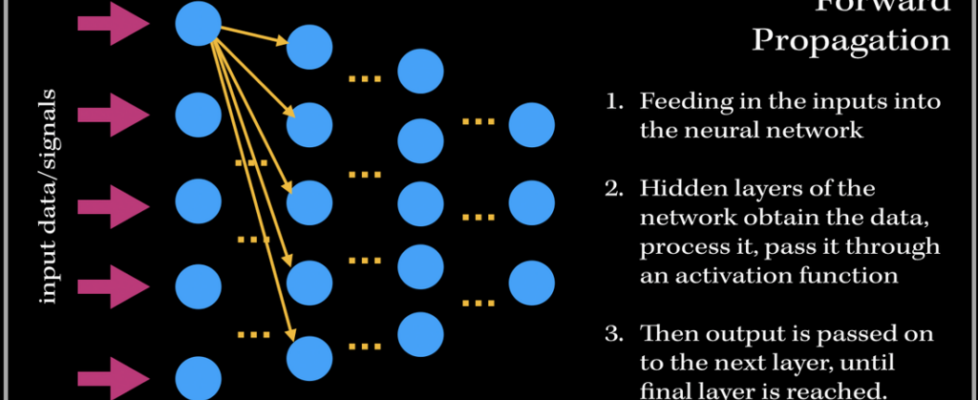

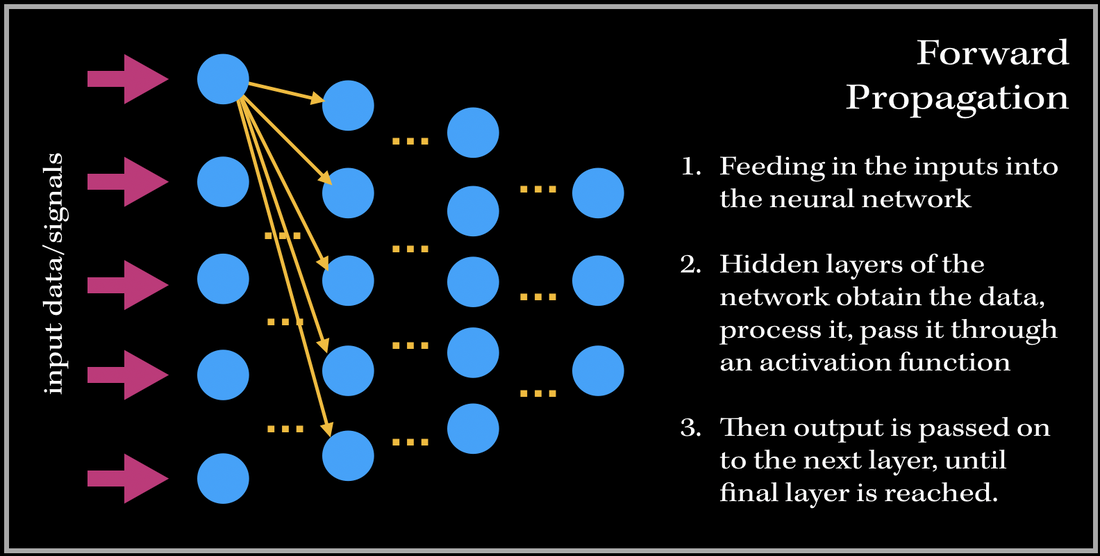

So what does the training process of this neurological-biological computer model-system (aka neural network) look like? It consists of two phases: 1). Forward Propagation and 2). Back propagation. Once we have preprocessed the dataset (such as normalization, reshaping your data to a specific dimension..etc.), we are ready for the training process. We first forward propagate our data—meaning we feed in the inputs into our built neural network.

Before we get into the deep math, let’s define some variables. These definitions are applied to every example in this blog post!

- a denotes the neuron value at a particular level of the network (level number is denoted as a superscript of a)

- x denotes the input fed into the neural network

- w denotes the set of weights at each level

- z denotes the dot product of the weights and the previous layer inputs

- The activation function is denoted as the sigma symbol. We will be using the sigmoid function for the activation.

Back Propagation

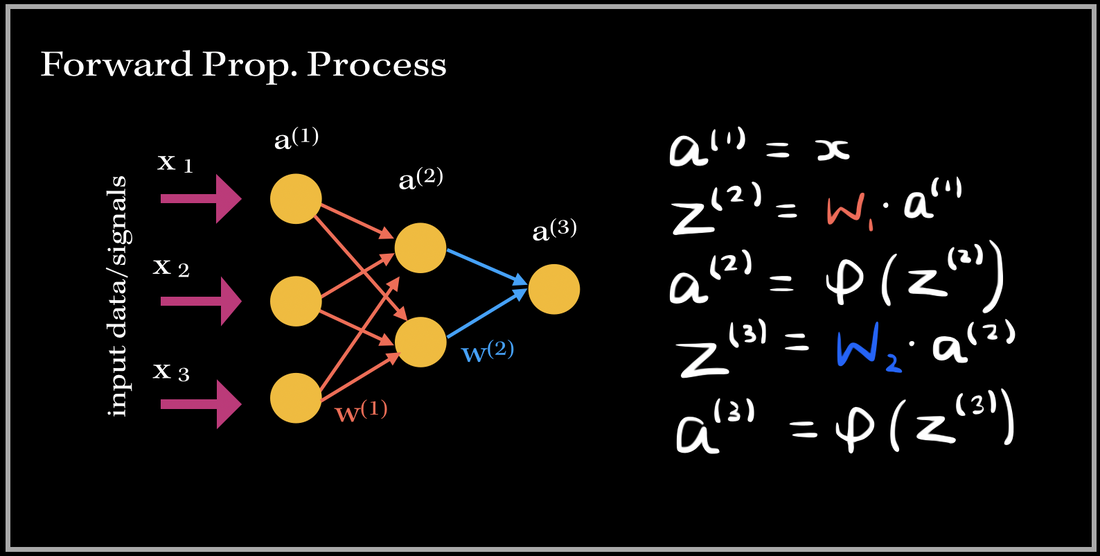

Basically, in Back Propagation, we need to adjust the weight parameters based on our loss function — whether it be calculating the mean squared loss, absolute mean loss or any other loss function we use — and our updated weights must head towards the right direction (in reducing the loss).

Let’s look at an example, and focus on one specific output neuron in a neural network model. We first pass in our input training data, and get a single output neuron of 0.5. However, the specific target value for the neuron is 1.0, so the cost function computes the error, and our optimizer uses the loss to back-propagate and change the weights to minimize the loss. This is why the process is at times called back-propagation of errors, since updates to one layer impact the next layer, and because of this backwards calculation technique, we are preventing redundant calculations.

The Process

- The back-propagation process starts from the output layer, where the predicted output value is analyzed with the targeted score, using our cost function.

- The partial derivative of the cost function with respect to each weight parameter is then computed. This forms the gradient vector — a vector of all the partial derivatives of each weight.

- As per the gradient descent algorithm, the weights (parameters) are then modified by subtracting the gradients multiplied by a constant factor (learning rate).

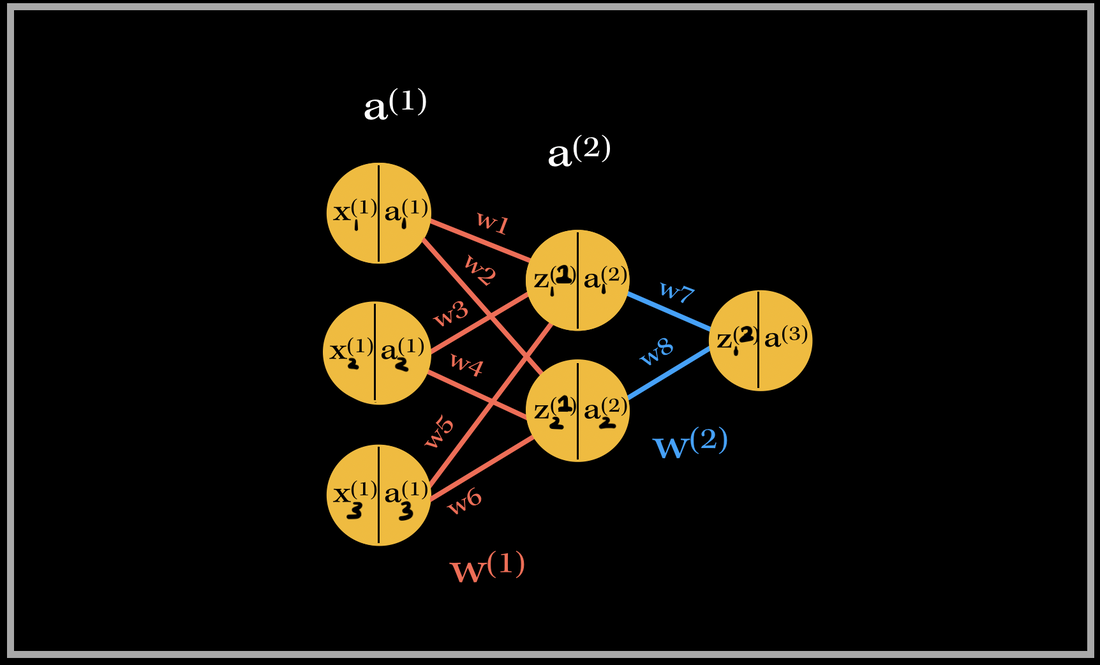

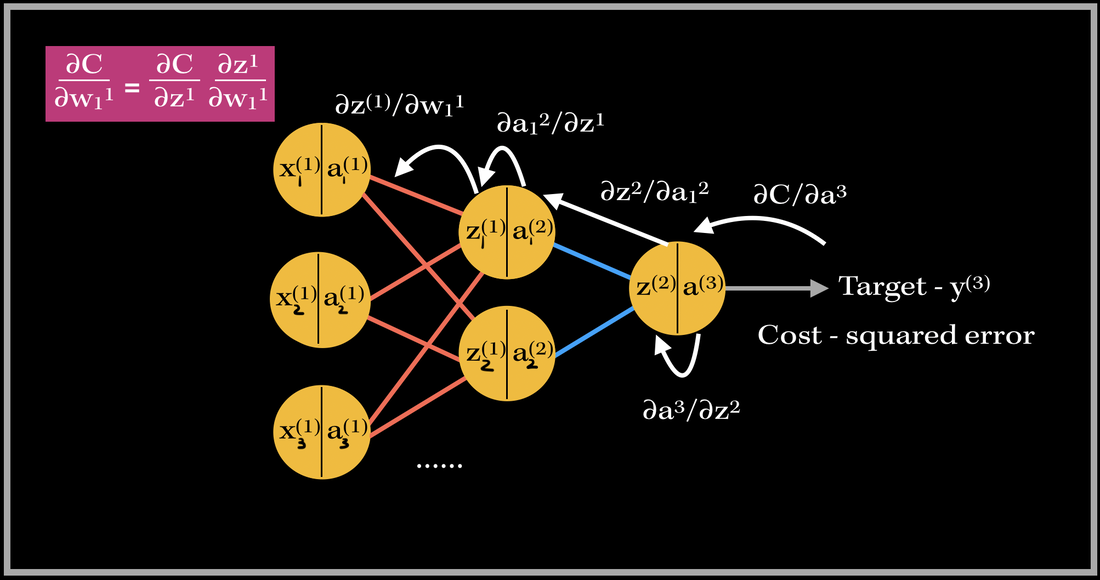

Let’s go do a back propagation run through with an example. Say we had a neural network with 3 input neurons, 2 neurons in the hidden layer, and 1 output neuron.

Back-propagation of the output layer

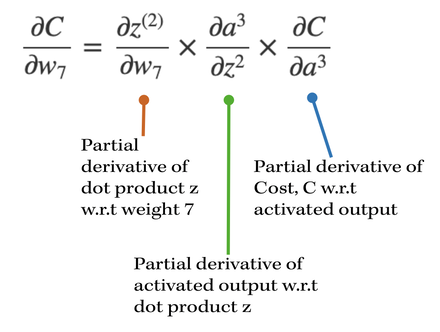

- The activation output, a^(3) is a function of weights in z^(2), and consequently is a function of the weights in w[2] (w7, w8).

- Therefore, we can take the derivative of the cost with respect to the output neuron value, a^3, and the utilize the chain rule by branching out and taking the derivative of the output w.r.t to the dot product, z^(2). Finally, in order to express the derivative with respect to the weight 7, we take the derivative of z^(2), the dot product, with respect to weight 7.

- By multiplying these three derivatives together, we can basically compute the update for weight 7!

|

After computing the partial derivatives, we have a final update value for weight 7. Now, the next step is to simply repeat this process for all weights in a recursive way, and update the weight value via gradient descent.

*NOTE: The algorithm substitutes the numerical values into the update equation, in order to perform the gradient descent update for weight 7!* |

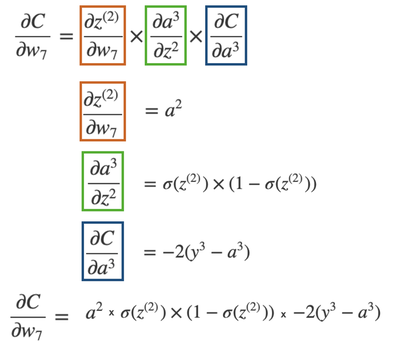

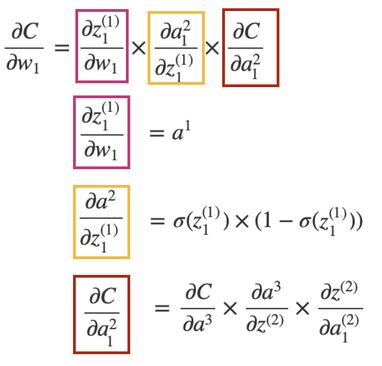

Back-propagation of a hidden layer

|

While the first two partial derivatives are similar to what we saw in the previous output layer back propagation, the third derivative looks slightly different.

In order to find the update of weight 1, we need to find derivative of the cost function with respect to the hidden layer activated output. The cost function is indirectly influenced by the activation in the hidden layer. By indirectly influenced, I mean that w7 contributes to the cost function by being multiplied with the hidden layer output. |

|

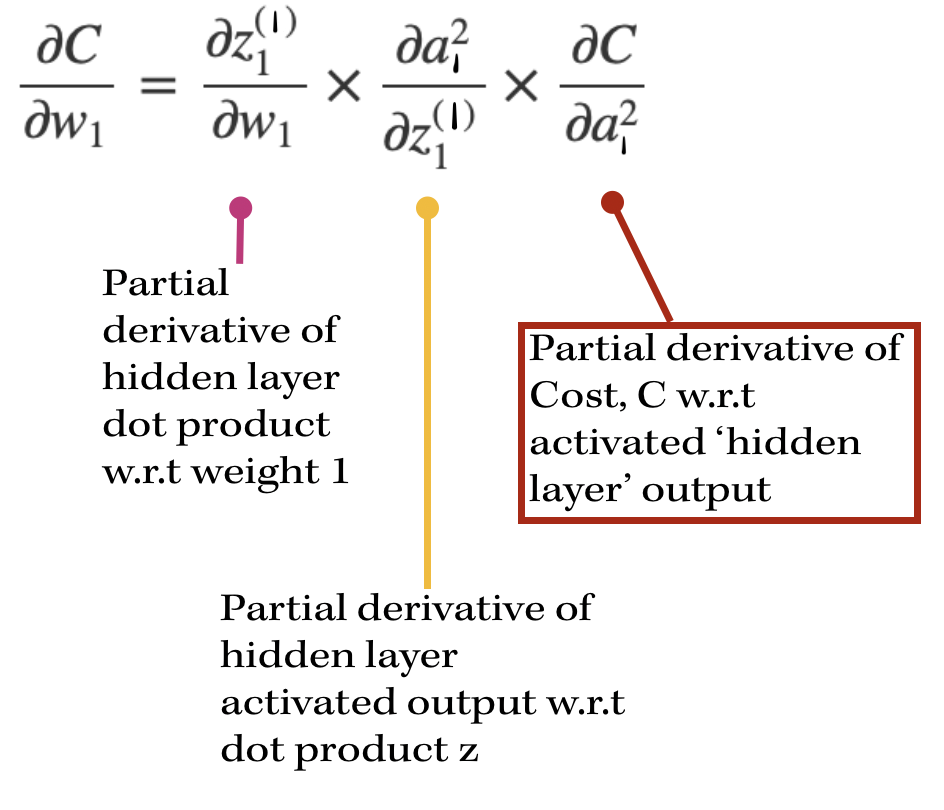

So in this case, we can see some similarities and yet some differences. The first derivative in this case evaluates to a^(1), since we are now focusing on the previous layer and set of inputs to the hidden layer (which is a^(1), in the neural network model above).

The next derivative is simply the derivative of our activation, in this case the sigmoid function. The next derivative is the most interesting part: it is composed of 3 more partial derivatives. |

This basically sums up finding the gradient of the network. As you can see, it requires lots of computation and derivatives!! Imagine the workload of computing the gradient vector of bigger neural networks with millions of parameters and neurons–backward propagation does this by using the previous layer’s computations to compute the updates for the next layers! It’s an amazing feat!

Back propagating in action

This same process occurs for every weight in the network during back propagation. Back Prop is one of the most important parts in training supervised learning neural network models! 🙂