The impact of direct air carbon capture on climate change

By Michael Nielsen, November

21, 2019

Note: Rough and incomplete working notes, me thinking out

loud. I’m not an expert on this, so the notes are tentative, certainly

contain minor errors, and probably contain major errors too, at no

extra charge! Thoughtful, well-informed further ideas and corrections

welcome.

In these notes I explore one set of ideas for helping address climate

change: direct air capture (DAC) of carbon dioxide – basically,

using clever chemical reactions to pull CO2 out of the atmosphere, so

it can be stored or re-used.

It’s tempting (and fun) to begin by diving into all the many possible

approaches to DAC. But before getting into any such details, it’s

helpful to think about the scale of the problem to be confronted. How

much will DAC need to cost if it’s to significantly reduce climate

change? Let’s look quickly at two scenarios for the cost of DAC, just

as baselines to keep in mind. I’ll discuss how realistic (or

unrealistic) they are below.

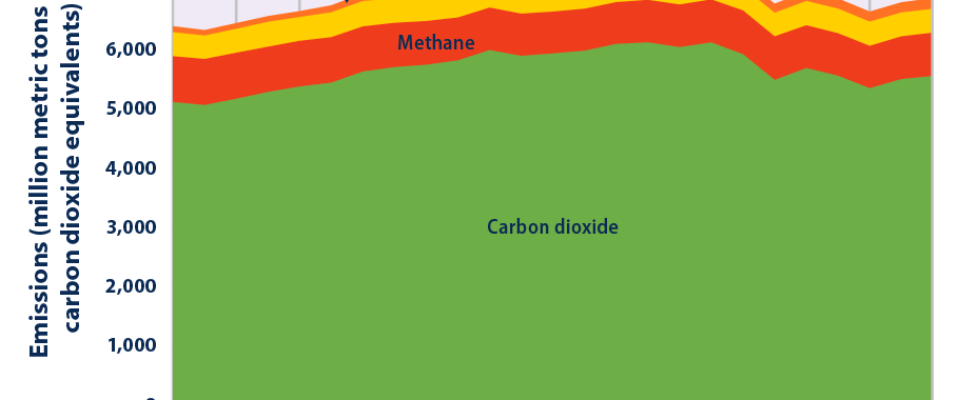

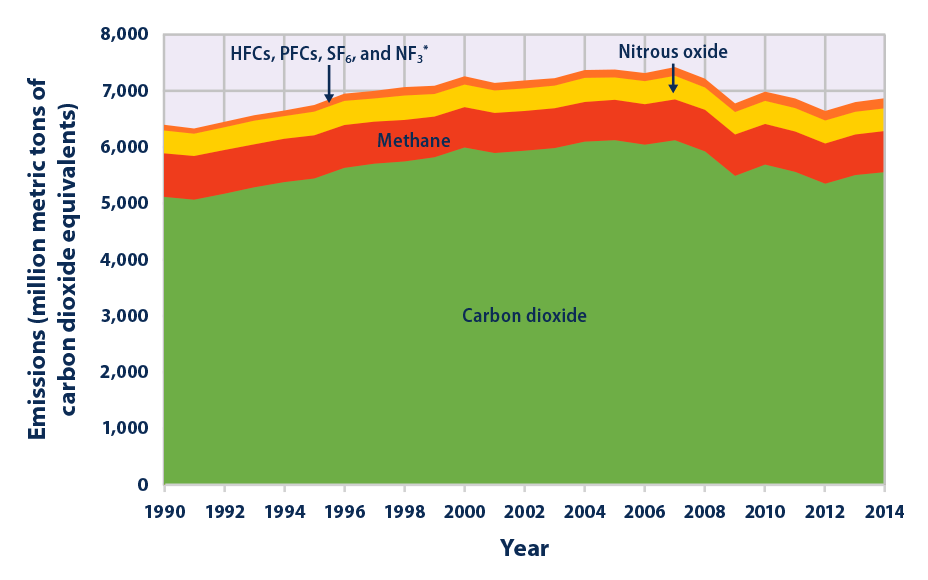

As of 2014, the United States emits about 6 billion tonnes of CO2

each year. Suppose it cost about 100 dollars per tonne of CO2 to do

direct air capture. To capture the entire annual CO2 production from

the US would cost about 600 billion dollars.

Source: US EPA

That’s a lot of money! As of 2019, the US military budget was about

700 billion dollars, so at 100 dollars per tonne the cost of DAC would

be a little less than the military budget. And it would be a little

over half of total energy spending in the US (about 1.1 trillion

dollars in 2017).

Suppose instead that direct air capture cost 10 dollars per tonne. In

this scenario the cost to capture all the US’s CO2 emissions would be

about 60 billion dollars per year.

That’s still a lot of money, but it’s starting to look like the cost

of a lot of things humans already do, in government, in commerce,

and even in philanthropy.

A particularly striking cost comparison is to the amount we already

spend on cleaning up or preventing air pollution. In 2011 the US

Environmental Protection Agency estimated that compliance with

the Clean Air Act cost about 65.5 billion dollars in 2010.

(The choice of year may sound a little odd and dated – why did I

go all the way back to 2010? It’s not a cherrypicked year –

rather, the EPA only very rarely reports on the costs of the Clean Air

Act, and it happens that 2010 is the most recent year for which an

estimate is available. It is, by the way, in line with the EPA’s

estimates for earlier years, and it seems reasonable to assume with

the cost in more recent years.)

So if DAC cost 10 dollars per tonne of CO2, the cost to make the US

carbon neutral would be comparable to the existing cost of compliance

with the Clean Air Act and associated regulations.

To make the comparison more concrete, let me mention the sort of

regulations (and benefits) the Clean Air Act involves. One example is

the imposition of emissions standards on vehicles, and the requirement

that they use catalytic converters to reduce pollution. Catalytic

converters typically run to a few hundreds dollars, and nearly 20

million cars and trucks are sold annually.

Presto: many billions of dollars each year in compliance costs!

Of course, what we get in exchange for this money is far cleaner skies

over our cities, and a much improved quality of life. I don’t just

mean that it’s pleasant to enjoy smog-free days; I also mean that this

makes a particularly large difference in the quality of life for

asthmatics and people with respiratory diseases, and certainly saves

many, many lives. Overall, it’s a very good exchange, in my opinion,

though I know people who disagree.

Returning to direct air capture, it’s worth keeping these two numbers

in mind as reference points: at 100 dollars per tonne for DAC, the

cost of DAC is comparable to the US military budget; and at 10 dollars

per tonne for DAC, the cost is comparable to the cost of compliance

with the Clean Air Act and related regulations.

None of this tells us at what cost point it’s possible to do DAC. It

doesn’t tell us how to set up a carbon economy to fund this, at any

price point, or how to get the political will for any necessary

changes (as was required for the Clean Air Act). Nor does it tell us

what to do about other greenhouse gases, or other countries.

Still, it’s helpful to have a ballpark figure to aim for. If DAC is

scalable at $100 per tonne, it starts to get very interesting. And at

$10 per tonne, the costs start to resemble things we’ve done before

for environmental concerns.

As we’ll see in a moment, the $100 cost estimate is at least plausible

with near-future technology. $10 per tonne is more speculative, but

worth thinking about.

What I like and find striking about this frame is that many people are

extremely pessimistic about climate change. They can’t imagine any

solution – often, they become mesmerized by what appears to be

an insoluble collective action problem – and fall into

fatalistic despair. This direct air capture frame provides a way of

thinking that is at least plausibly feasible. In particular, the $10

per tonne price point is striking. The Clean Air Act was contentious

and required a lot of political will. But the US did it, and many

other countries have implemented similar legislation. It’s a specific,

concrete goal worth thinking hard about.

Incidentally, in most analyses like this it’s conventional to engage

in a lot of cross-comparison between approaches. Analyses which don’t

do such cross-comparisons tend to get criticised: “but why

didn’t you consider [other approach] which [works better

because]”. Doing such comparisons makes good sense if your goal

is to figure out where to invest resources, or what outcomes are

likely. But those aren’t the point of this analysis. The point here is

to more clearly understand the bounds on the overall complexity of the

problem. If some approach can work at a reasonable price point, then

better solutions are certainly possible. So let me say: I think we can

likely do much better than direct air capture. But I think this

analysis is useful for bounding the difficulty of the problem.

I’ve been talking at an abstract level, in terms of government

programs and so on. It’s also worth putting these numbers in

individual terms. On average, US citizens produce about 20 tonnes of

CO2 emissions each year. At $100 per tonne for DAC, that’s $2,000 each

year. At $10 per tonne, it’s $200 each year. Again, we can see that

the $10 per tonne price point looks very feasible – $200 is

quite a bit of money for most people, but it’s about what they

routinely spend for many important things in their life. And while

$2,000 really is a lot of money for most people, it’s also much less

than the median US citizen routinely spend for many important aspects

of their lives.

There’s a lot of variation in other countries, but among large,

wealthy countries the US is on the high end of per-capita

emissions. In countries like France and Sweden, which have worked hard

on reducing emissions, the numbers tend to be more like 5 tonnes of

CO2 emissions per year. And so $100 DAC comes out to $500 per person

per year, and $10 DAC to $50 per person per year.

I guess it’s not currently popular to memorize numbers and simple

models of climate change. Still, I wish people discussing climate

change knew not just these numbers (or some equivalently informative

set), but also many more. I’ve sat in meetings about climate change

where many attendees appeared to have almost no quantitative awareness

of the scale of the problem. Without such an awareness of, and

facility with, quantitative models, their only chance of making

substantive progress is by accident, in my opinion.

How much will direct air capture cost, in the near future?

So, how much does direct air capture actually cost? And what are the

prospects for driving the costs down?

Unfortunately, it’s not very clear. Although technologies for direct

air capture have been used since the 1930s, it’s usually been done on

a small scale, for reasons unrelated to climate. Doing it at the giant

scales – ultimately, billions of tonnes! – required to

impact the climate is quite another matter.

If you read around about direct air capture, you discover a few

things: there are many approaches, with widely-varying cost estimates;

those estimates are often back-of-the-envelope theory, not even based

on a pilot, much less an operating large-scale plant. There’s nothing

quite as inexpensive as an industrial plant that exists only on

paper. Or, as I once overheard someone say, half cynically, half

optimistically: “my favourite form of science fiction is the

pitch deck.”

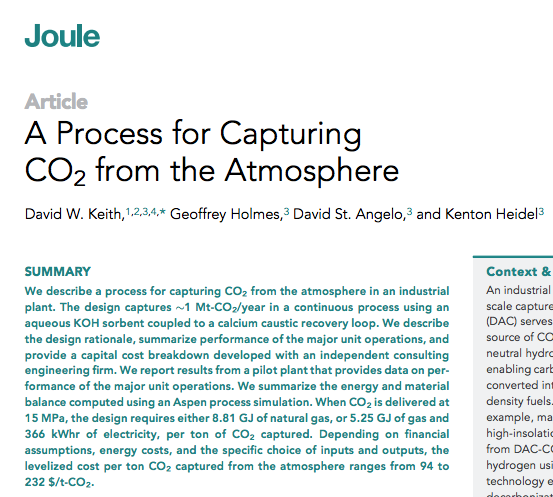

One of the most detailed proposals comes from the company Carbon

Engineering, which has been working on direct air capture

since 2009. In 2018 they published a paper estimating the costs

associated to direct air capture. Their basic proposal is to build

cooling towers, filled with a liquid that absorbs CO2, and run big

fans to blow air from the atmosphere over that liquid. They then run

the resulting material through a second process that produces nearly

pure CO2 as output. That CO2 then needs to either be stored or else

somehow re-used, perhaps as raw material for manufacturing fuel or

something similar. Obviously, this is a very simplified account of

what they’re doing, that leaves many details out!

Unlike many proposals, Carbon Engineering isn’t just working on

paper. They’ve built a small pilot plant in the town of Squamish,

British Columbia, an hour north of Vancouver. It runs at a rate of

hundreds of tonnes of CO2 captured per year. They’ve attempted to do

detailed costings of all components necessary to make a large-scale

plant, one with a capacity, if run at full utilization (they estimate

it’ll be run at about 90% utilization), of removing a million tonnes

of CO2 from the atmosphere each year. They estimate that it’ll cost

from $94 to $232 per tonne of carbon removed. The exact amount depends

on details of the configuration the plant is run in, and also reflects

things like possible variations in interest rates on debt, and so on.

It’s tempting to be skeptical of this proposal. For one thing, in the

short term Carbon Engineering has a vested interest in making their

direct air capture scheme look attractive and inexpensive. And there’s

also just natural human entrepreneurial optimism, and the fact that,

by definition, you can’t anticipate the details of unexpected

problems. So caution is called for. I also lack the expertise to

seriously evaluate the technical details of their proposal. While to

my eye, it looks as though Carbon Engineering has been careful, maybe

they’ve missed some important factor, and their estimates are way

off. On the other hand, there are at least quite a few eyes on it

– although the paper was published just a year ago, in 2018,

it’s already been cited 132 times, and it’s clear it’s seen as

something of a gold standard.

There are some interesting critiques of direct air capture in the

scientific literature. For instance, this 2011 paper by House et

al claims a minimal cost of $1,000 per tonne, based on a relatively

general argument, whose main input appears to be the cost of

electricity. The analysis is quite complicated, and I don’t understand

many of the details (working on it, but it’s a real research project

to track everything down!) The essential gist seems to be: when you

separate the CO2 from the atmosphere, you’re ordering the system, and

so necessarily lowering the entropy of the system. The second law of

thermodynamics tells us there will be an intrinsic energy cost

associated to doing this, even if done with maximal efficiency; that,

in turn, puts some constraints on the costs. In any case, they

conclude that “many estimates in the literature appear to

overestimate air capture’s potential”.

The Carbon Engineering paper mentions this paper and similar

critiques, and rebuts it with an argument that amounts to “well,

we actually went and built a plant which works, and we did detailed

costings of how to scale it up”. This is a good start on a

rebuttal, but obviously as an outsider it’d be good to go back and dig

into both pro and con details much more than I have. That may be a

project I do in the future. For the sake of argument, and the

remainder of these notes, let’s stick with Carbon Engineering’s

numbers, but keep in mind that they should be taken with a grain of

salt, until examined much more closely.

I must admit, part of the reason I’m inclined to be sympathetic toward

Carbon Engineering’s estimate is that I read lead author (and Carbon

Engineering’s cofounder) David Keith’s book about a different

topic, solar geoengineering. Keith seemed to me to be very honest

in the book, carefully describing many of his own uncertainties, the

complexities of the problem, and giving charitable explanations of the

position of his critics. None of that makes him correct, but I’m

inclined to believe he’s careful, serious, and worth paying attention

to.

An influential prior study of DAC came in 2011 from an American

Physical Society (APS) study. The costs estimated were much higher,

more in the ballpark of $600 per tonne of CO2.

What accounts for the difference – likely a factor of 3 or more?

In the words of Carbon Engineering’s paper:

The cost discrepancy is primarily driven by divergent design choices

rather than by differences in methods for estimating performance and

cost of a given design. Our own estimates of energy and capital cost

for the APS design roughly match the APS values.

This is then followed by a relatively detailed (and, to my eye,

plausible) account of the differences in design choices, and how

Carbon Engineering improved on the prior design decisions. I’ll say a

bit more about that below.

On its face, the numbers in the Carbon Engineering paper don’t seem so

encouraging. Let’s call it $200 per tonne. At that level, for the US

to achieve carbon neutrality would cost more than the US currently

spends on energy in total.

What about other approaches? Let’s broaden the field, and consider

negative emissions technologies in general, especially those pulling

CO2 directly out of the atmosphere in some way. (In contrast to

technologies which capture carbon at the source of production –

often a less costly but also less general, more bespoke approach.)

Earlier this year, the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering,

and Medicine released an informative report surveying negative

emissions technologies. In the report, they attempt to estimate both

cost ranges and the scalability of many different technologies. If

you’re interested, there’s a good summary on pages 354-356 of the

report.

I won’t summarize all their results here. But there is much

(cautiously) encouraging news. There are a lot of possible negative

emissions technologies. One approach is coastal blue carbon –

storing carbon in mangroves, marshes, and sea grasses, the kind of

ecosystems one sees along the coastline. This perhaps doesn’t sound

terribly promising. But the big advantage is that the carbon tends to

be stored underground, in the soil, and can be stored there for

decades or centuries. The NAS survey reports a cost estimate of $10

per tonne.

That price point is much more encouraging than Carbon

Engineering’s. Unfortunately, the report also projects a

“potential [global] capacity with current technology and

understanding” of 8-65 billion tonnes. That’s not enough for

even two years of global CO2 production. So at most, this can simply

help out.

Another approach is based on storing carbon in forests. The National

Academies report’s estimated price is somewhat higher – from

$15-50 per tonne of CO2. (I don’t know if that includes proper burial

– when trees die most of their CO2 is typically returned to the

atmosphere). But the approach is also much more scalable, with an

estimated global capacity of from 570 to 1,125 billion tonnes, using

“current technology and understanding”. Per year, the NAS

estimates a capacity of 2.5 to 9 billion tonnes, again using current

technology and understanding. That’s global, so it’s not enough to

make the world carbon neutral (global CO2 emissions are almost 40

billion tonnes per year). But it’s starting to put a sizeable dint in

the problem.

(A caveat to the discussion in this section: I haven’t been careful

about which of these numbers include the cost of storing or utilizing

carbon. That’s a genuine cost. My impression is that it’s likely to

cost less than $20 per tonne, maybe much less, or even turn a

profit. This is based in part on the cost of storing CO2 in the Utsira

formation – a giant undersea aquifer off Scandinavia –

where several million tonnes of CO2 have been stored at a

Wikipedia-reported price of 17 dollar per tonne. If this impression is

correct then the cost of capturing CO2 is likely to either dominate or

in worst case be comparable to the cost of storage and

utilization. Still, a more detailed analysis would be careful about

this costing.)

How much can the costs drop?

These numbers are tantalizing. Apart from the (probably not scalable)

coastal blue carbon, they’re about an order of magnitude away from

where they need to be for climate to be a problem of similar order to

air pollution. But the numbers are also based on “current

technology and understanding”.

How much can these costs drop with improvements in technology? And are

there other ways of dropping the effective costs?

The most famous technology cost curves are those associated to Moore’s

Law – the exponential increase in transistor density in

semiconductors, and associated things like computer speed, memory,

energy efficiency, and so on.

This is, in fact, a common (though not universal) pattern across

technologies. It seems to have first been pointed out in a 1936 paper

by the aeronautical engineer Theodore Wright. Wright observed the cost

of producing airplanes dropped along an exponential curve as more were

produced. Very roughly speaking, for each doubling in production,

costs dropped by about 15 percent. Essentially, as they made more

airplanes, the manufacturers learned more, and that helped them lower

their costs.

This pattern of exponential improvement is seen for many technologies,

not just in semiconductors and airplane manufacture. It’s been common

in energy too. For instance, the cost of solar energy has dropped by

roughly a factor of 100 over the past four decades

(link, link). That cost reduction was driven in part by

technological improvement, and in part by economies of scale.

One wonders: will the cost of direct air capture or some other

negative emission technology follow something like Wright’s Law? If

so, one might hope that it would drive the cost of carbon capture in

some form down below 10 dollars per tonne. Indeed, it’s even possible

to start to think about whether there’s ways it could be made net

profitable.

Unfortunately, while Wright’s Law is interesting, it’s far from a

compelling argument. Indeed, it’s a little silly to call it a Law:

it’s an observed historical regularity, an observation about the past

for certain technologies. If you’re Intel, planning for 5 to 10 or

more years from now, you need to set targets. You may perhaps be

able to project reliably a few years on the basis of in-train

improvements. But longer-term improvements may be more speculative,

and require new ideas, ideas that by definition you can’t directly

incorporate into your current models. Studying history is an

alternative approach to help set plausible targets. But eventually

such historical regularities break down. Indeed, we see this in recent

years where many aspects of Moore’s Law have started to break down.

And so the fundamental problem here is that we don’t know how much the

costs of DAC will go down. At best, we can make guesses. That’s a

nervous position to be in – the usual situation for challenging

problems!

To make this more concrete, let’s come back to Carbon Engineering’s

proposal for DAC. Here, in more detail, is how they cut the cost by a

factor 3 or so from the APS study. The details won’t make much sense,

unless you’ve read the paper (or similar work); what’s important is to

read for the general gist:

The cost discrepancy is primarily driven by divergent design

choices… The most important design choices involved the

contactor including (1) use of vertically oriented counterflow

packed towers, (2) use of Na+ rather than K+ as the cation which

reduces mass transfer rates by about one-third, and (3) use of steel

packings which have larger pressure drop per unit surface area than

the packing we chose and which cost 1,700 $/m3, whereas the PVC

tower packings we use cost less than 250 $/m3. … In rough

summary, the APS contactor packed tower design yielded a roughly

4-fold higher capital cost per unit inlet area, and also used

packing with 6-fold higher cost, and 2-fold larger pressure drop.

The paper continues with a discussion of why the APS made those

different design choicees, and also with a discussion of some

differences in the way input energy was used in Carbon Engineering’s

design versus the APS design.

I’m not an industrial chemist, but to me those changes sound like

low-hanging fruit. But they’re also not the kind of low-hanging fruit

that the APS could have planned for in 2011. If they could have

planned for it, they would have come up with a different cost

estimate.

Of course, low-hanging fruit is what you’d expect. Carbon Engineering

has been, until recently, a tiny company, with a small handful of

staff. They were founded in 2009, and appear to have subsisted on

relatively small grants and seed funding until 2019, when they raised

68 million dollars. It’s interesting to think about what they’ll

achieve with that funding. Hopefully, they’ll be able to pick some

higher-hanging fruit. Assuming their initial cost estimates bear out,

for this design, will it be possible for them (or someone else working

on direct air capture) to achieve another factor of 3 reduction in

cost?

I’ve been focusing on cost reductions due to better design and

technology. In fact, part of the job will be done in a very different

way. The carbon intensity of a country is the CO2 emissions per

dollar of GDP. Carbon intensities in the US dropped more than 18% per

decade from 1990 to 2014, the latest year for which the World Bank

reports numbers. This isn’t surprising: all other things equal, most

people and companies try to keep doing things in more energy-efficient

ways, since energy costs them money. If this drop in carbon intensity

continues, it means that considered as a fraction of the total

economy, the cost of DAC will go down. Effectively, it’s as though

we’re automatically making progress toward $10 DAC, at a rate of about

18 percent per decade. On its own that won’t make DAC economically

feasible. But over two or three decades, it’ll help a lot.

It’s also interesting to think about cost reductions due to plausible

emissions reductions. As noted earlier, in countries such as France,

Sweden, etc, average emissions per capita are something like 4 times

lower than in the US. This is often attributed causally to their

extensive use of nuclear power; nuclear certainly plays a large role,

but as far as I can see it can only be part of the story (since

electricity production is only responsible for a moderate fraction of

total emissions). Rather, it’s that they’ve also been more serious

than the US in other ways about reducing emissions; their use of

nuclear is, in part, a symptom of this seriousness, not the cause. In

any case, such examples illustrate that nuclear plus other moderate

efforts can lead to large emissions reductions.

(I should point out: of course, drops in carbon intensity and

emissions reductions are intertwined, not independent! I’ve mentioned

them separately because there are ways in which they’ve very different

kinds of goals with, for example, different kinds of expression in

policy.)

Of course, neither changes in carbon intensity nor emissions

reductions are literally the same as a drop in price of direct air

capture. But considered as a fraction of the economy they may as well

be; it’s a kind of drop in the effective cost of DAC. And so I think a

factor 10 or more reduction in the effective cost of DAC is plausibly

possible, in part through technological improvements, in part through

emissions reductions as already implemented in countries with similar

standards of living, and in part through reduced carbon intensity. Put

another way: it’s plausible that doing DAC to make the US carbon

neutral ends up costing an amount comparable to or less than the

current cost of the Clean Air Act, as a fraction of the total

economy. That seems encouraging.

I’ve focused a lot on direct air capture, and it sounds like I’m

bullish about this approach. Actually, I’m too ignorant to have a

really strong opinion. From my point of view, a big part of

concentrating here was simply that (a) there was what seemed a

particularly juicy paper to dig into, and (b) as I said at the start,

this could be treated as a boundary case, setting a kind of worst-case

scenario. It’s entirely possible – indeed, likely, – that

other approaches to dealing with climate are considerably better. But

this already looks promising. My tentative conclusions are that

direct air capture offers a promising but far from certain approach

to making major progress on climate change. And, more broadly:

negative emissions technologies offer a promising approach to making

major progress on climate change.

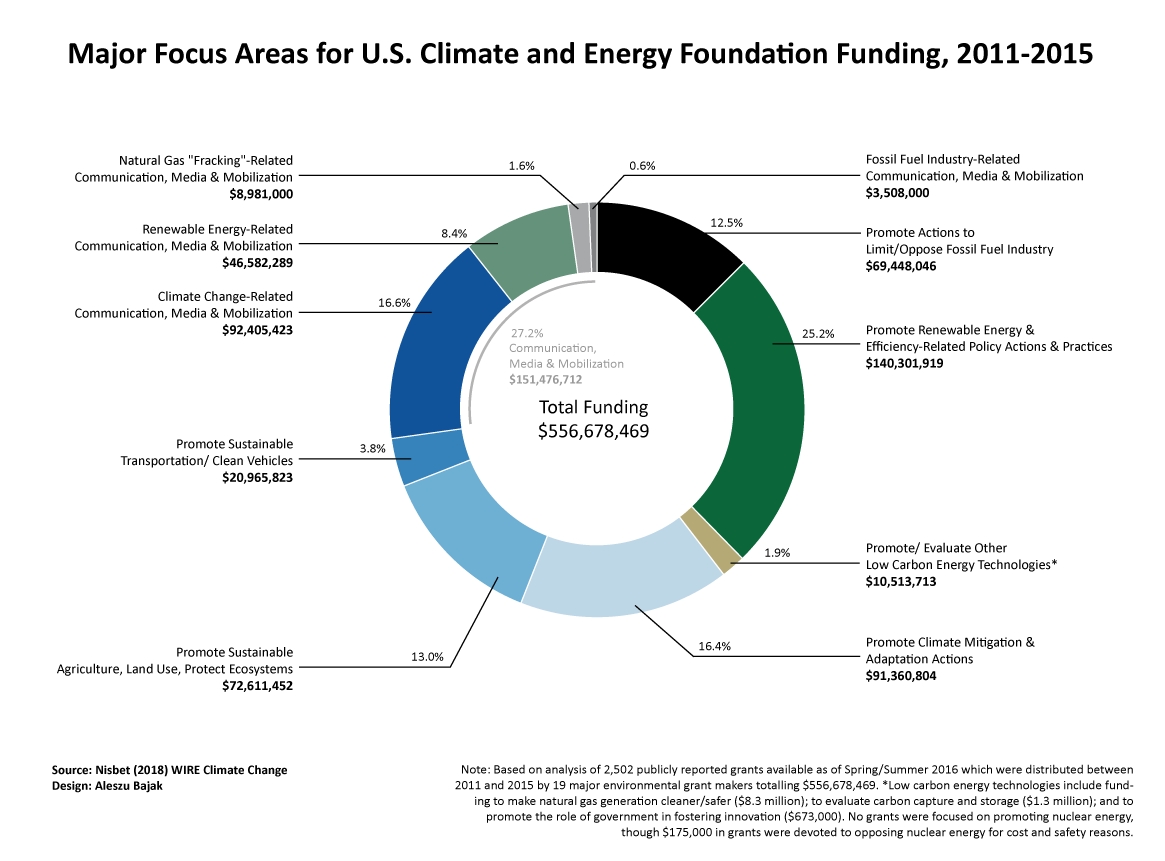

I got interested in direct air capture in part after reading Matt

Nisbet’s survey of US climate and energy foundation funding

(summary here, with a link to the full survey). Here’s his

summary chart. Note that it covers funding from 19 major funders of

climate and energy work, and the years from 2011 to 2015:

You see enormous sums of money going into renewable energy,

sustainable aagriculture, and into opposing fossil fuels. But just a

tiny fraction of the spending – 1.9%, or just over 10 million

dollars – went to other low carbon energy technologies. And of

that, just $1.3 million went to evaluate carbon capture and storage.

Now, admittedly, these numbers focus on just a tiny slice of the total

funding pie (US foundation funding), and are somewhat outdated. In

particular, the last few years have seen substantial progress on

investment in negative emissions technologies (as witness the $68

million invested in Carbon Engineering). Still, my impression is that

the qualitative picture from Nisbet’s research holds more broadly.

Humanity’s collective priorities are research and development focused

on renewable energy sources, especially solar and wind; and

anti-fossil fuel messaging and lobbying. By contrast, negative

emissions technologies like DAC are receiving relatively little

funding.

As a non-expert, I’m reluctant to hold too firm opinions here. But,

frankly albeit tentatively I think this makes no sense! Of course,

renewables (say) should receive a lot of funding. But if you genuinely

believe climate change is a huge threat, then we should collectively

and determinedly pursue lots of different strategies. Direct air

capture (and, more broadly, negative emissions) look very underfunded

and underexplored. Yes, it requires considerable improvement. But

compared to other historic technologies, it’s within striking distance

of being able to have a huge impact, especially considering the

relatively minor effort so far put into it.

Conclusion

This is a tiny slice through a tiny slice (direct air capture) of the

climate problem. Climate is intimidating in part because the scale of

understanding required is so immense. You can spend a lifetime

studying the relevant parts of just one of: the climate itself, the

energy industry, solar, wind, nuclear, politics, economics, social

norms. It’s extremely difficult to get an overall picture; it’s easy

to miss very big things. I wrote these notes mostly because the only

way I know to get a handle on big problems is to start by doing

detailed investigations of very tiny corners. So consider this one

very tiny corner.

To finish, I can’t resist reporting an uncommon opinion: overall, and

over the long term, I’m optimistic about climate.

I’ve focused on direct air capture, but it seems to me there are many

other promising approaches. I believe humans will figure out how to

address climate change. There will be a lot of suffering along the

way, much of it falling to the world’s poorest people. That’s a

terrible tragedy, and something we’re too late to entirely avert;

indeed, it’s very likely already happening. But over the long term

work on this problem will also lead us to strengthen existing

institutions, and to invent new institutions, institutions which will

make life far better for billions of people. It’s a huge challenge,

but I think we’ll rise to the challenge, and make human civilization

much better off for it.

Acknowledgments: Thanks to Andy Matuschak for conversations about

climate.

Please help support my work on Patreon, and

please follow me on Twitter.