Learning Under Constraints: How Hypothesis-Driven Synthetic Data Improves Marketing Measurement

This article is part of an ongoing exploration of how marketing measurement systems must evolve as signal observability declines.

Modern marketing measurement looks like a data science problem — until you examine how the data is actually created. In advertising systems, data isn’t collected through clean random sampling. It’s generated by decisions: budget allocations, bidding strategies, targeting rules, frequency caps, auction dynamics, and, increasingly, privacy-driven aggregation. Those choices determine what we observe — and just as importantly, what we never see.

This creates a fundamental constraint for anyone building MMMs, incrementality models, or optimization systems. The data reflects a narrow slice of reality shaped by prior policies. Counterfactuals are sparse. Feedback loops distort signals. And key drivers of performance — saturation, fatigue, lag, intent — are often weakly identifiable at best.

Under these conditions, the idea that we can simply “let the data speak” is no longer credible. The real question is not whether we make assumptions. We have to. The question is whether those assumptions remain implicit and fragile, or become explicit, testable, and governed.

This is where hypothesis-driven synthetic data generation becomes a powerful — and underused — capability for marketing measurement and data science teams.

Why empirical learning breaks down in modern advertising systems

If you’ve worked on MMM or incrementality, these constraints will feel familiar:

- Spend is endogenous. MMM only observes spend levels that were already chosen, making response curves and saturation hard to identify.

- Exposure is selective. Targeting skews delivery toward high-intent users, inflating observed performance if correlation is mistaken for incrementality.

- Auctions censor outcomes. You rarely observe the counterfactuals associated with losing bids.

- Privacy aggregation reduces observability. User-level structure disappears precisely where non-linearities and interactions matter.

- Feedback loops shape future data. Optimization decisions today influence what can be learned tomorrow.

In short: the dataset is a byproduct of a decision system.

When data is policy-generated, learning without assumptions is impossible. The danger isn’t bias alone — it’s false confidence in conclusions drawn from structurally limited evidence.

What hypothesis-driven synthetic data actually is (and isn’t)

Synthetic data is often misunderstood as “fake data that looks real.” That framing misses the point.

Hypothesis-driven synthetic data starts with an explicit specification of how the system might work:

- How exposure is generated (allocation rules, targeting, auctions)

- How outcomes respond (linear vs diminishing returns, saturation, lag)

- What latent variables exist (intent, competition, seasonality)

- What constraints apply (budgets, caps, aggregation).

From that hypothesis, we generate datasets representing plausible data-generating regimes — not ground truth. Each dataset is a counterfactual sandbox that lets us ask:

- Can this MMM recover correct signs, monotonicity, and relative sensitivities?

- When does an observational incrementality estimator break under selection bias?

- Are budget recommendations stable across plausible worlds, or highly assumption-dependent?

This is not traditional sensitivity analysis. Sensitivity analysis perturbs parameters within a fixed dataset. Synthetic data perturbs the data-generating process itself.

And it doesn’t “solve” causal identification. Instead, it makes non-identifiability visible, which is exactly what decision-makers need to see.

Why this matters for MMM and incrementality in practice

MMM: stress-testing structure before trusting outputs

MMMs are often asked to deliver:

- Historic ROI

- Marginal ROI

- Response (saturation) curves

- Optimized budget recommendations

But these outputs are produced in an environment where:

- channels are correlated

- Spend is chosen, not randomized

- Lag and saturation trade off statistically

- Privacy constraints limit signal.

Synthetic data lets teams test whether these outputs are structurally recoverable at all, given the data they have.

If a model cannot recover known response shapes or directional effects in synthetic worlds, it will not reliably recover them in production. This turns synthetic data into a design-time stress test, not a post-hoc justification.

Incrementality: turning selection bias into a mechanism, not a debate

Incrementality is fundamentally about causal impact — what happened because the ad ran, beyond baseline demand. But in real systems, exposure is rarely random.

By simulating latent intent that influences both exposure and outcome, synthetic data makes selection bias concrete. Teams can explore:

- When observational lift is directionally misleading

- How large bias can become under realistic targeting

- When experiments are required to resolve uncertainty

This reframes MMM vs incrementality from a methodology argument into a system-level question: where does each approach break, and what additional evidence would reduce decision risk?

A minimal example: two plausible worlds, very different decisions

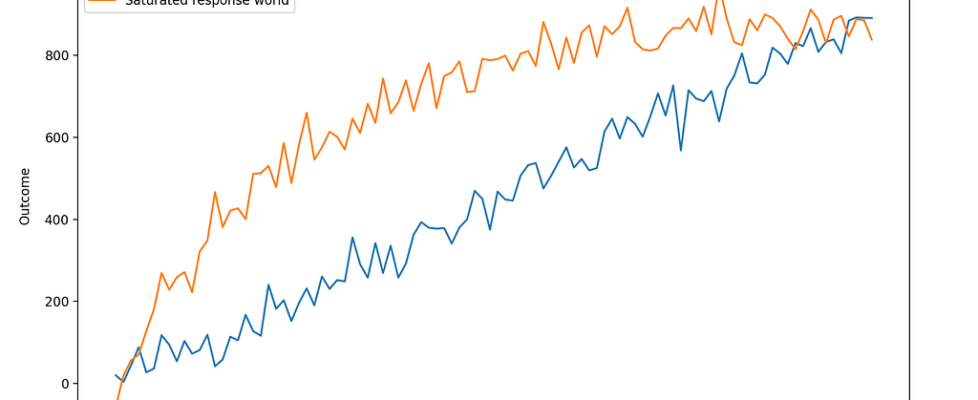

Below is a deliberately simple illustration. Two different response regimes — linear and saturated — can both look reasonable in historical data, yet imply very different marginal ROI and budget decisions.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

np.random.seed(42)

spend = np.linspace(0, 1000, 100)

def linear(spend, beta):

return beta * spend

def saturated(spend, alpha, gamma):

return alpha * (1 - np.exp(-gamma * spend))

y_linear = linear(spend, 0.9) + np.random.normal(0, 40, 100)

y_saturated = saturated(spend, 900, 0.004) + np.random.normal(0, 40, 100)

Both can fit observed data reasonably well. But one implies “keep spending,” while the other implies “reallocate aggressively.” The risk isn’t model error — it’s decision fragility driven by weakly identified structure.

If a model cannot recover known response shapes in synthetic worlds, it won’t reliably recover them in production.

Robust decision behavior is a stronger validation criterion than data realism

A common mistake is validating synthetic data by asking, “Does it look realistic?” That’s a weak standard.

More useful criteria are:

- Structural fidelity — are dependencies and constraints encoded correctly?

- Model behavior — do learned signs and sensitivities align with the hypothesis?

- Decision robustness — do recommendations remain stable across plausible regimes?

The most important question isn’t which assumption is correct. It’s which decisions change when assumptions change.

In decision systems, fragility — not bias alone — is the real risk.

A practical operating model for teams

This approach doesn’t require massive infrastructure. In practice, it works best as a lightweight discipline:

- Maintain a hypothesis inventory

Explicitly document assumptions about response shape, saturation, lag, interactions, selection, and noise. - Generate competing synthetic worlds

Not one dataset — a range of plausible regimes. - Run your measurement stack end to end

Fit MMMs, evaluate incrementality estimators, and produce optimization outputs. - Read results like a reliability engineer

Where are outputs stable? Where are they fragile? What additional data or experiments would reduce uncertainty? - Communicate as scenarios, not point estimates

Executives don’t need false precision. They need bounded, decision-relevant guidance.

Synthetic data should never be judged on accuracy. Its role is to improve decision safety.

The bigger shift

As advertising systems become more complex and constrained, the bottleneck is no longer data volume — it’s assumption clarity.

Hypothesis-driven synthetic data generation helps data science teams:

- Surface hidden assumptions

- Stress-test models before real budget is at risk,

- Align measurement with how decisions are actually made.

It doesn’t replace MMM, experiments, or attribution. It makes them safer to use. In policy-generated, privacy-first environments, that shift — from fitting models to designing reliable learning systems — is no longer optional. It’s a core capability.

Learning Under Constraints: How Hypothesis-Driven Synthetic Data Improves Marketing Measurement was originally published in Towards AI on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.