IABIED Book Review: Core Arguments and Counterarguments

Published on January 24, 2026 2:25 PM GMT

The recent book “If Anyone Builds It Everyone Dies” (September 2025) by Eliezer Yudkowsky and Nate Soares argues that creating superintelligent AI in the near future would almost certainly cause human extinction:

If any company or group, anywhere on the planet, builds an artificial superintelligence using anything remotely like current techniques, based on anything remotely like the present understanding of AI, then everyone, everywhere on Earth, will die.

The goal of this post is to summarize and evaluate the book’s core arguments and the main counterarguments critics have made against them.

Although several other book reviews have already been written I found many of them unsatisfying because a lot of them are written by journalists who have the goal of writing an entertaining piece and only lightly cover the core arguments, or don’t seem understand them properly, and instead resort to weak arguments like straw-manning, ad hominem attacks or criticizing the style of the book.

So my goal is to write a book review that has the following properties:

- Written by someone who has read a substantial amount of AI alignment and LessWrong content and won’t make AI alignment beginner mistakes or misunderstandings (e.g. not knowing about the orthogonality thesis or instrumental convergence).

- Focuses on deeply engaging solely with the book’s main arguments and offering high-quality counterarguments without resorting to the absurdity heuristic or ad hominem arguments.

- Covers arguments both for and against the book’s core arguments without arguing for a particular view.

- Aims to be truth-seeking, rigorous and rational rather than entertaining.

In other words, my goal is to write a book review that many LessWrong readers would find acceptable and interesting.

The book’s core thesis can be broken down into four claims about how the future of AI is likely to go:

- General intelligence is extremely powerful and potentially dangerous: Intelligence is very powerful and can completely change the world or even destroy it. The existence proof that confirms this belief is the existence of humans: humans had more general intelligence than other animals and ended up completely changing the world as a result.

- ASI is possible and likely to be created in the near future: Assuming that current trends continue, humanity will probably create an artificial superintelligence (ASI) that vastly exceeds human intelligence in the 21st century. Since general intelligence is powerful and is likely to be implemented in AI, AI will have a huge impact on the world in the 21st century.

- ASI alignment is extremely difficult to solve: Aligning an ASI with human values is extremely difficult and by default an ASI would have strange alien values that are incompatible with human survival and flourishing. The first ASI to be created would probably be misaligned, not because of malicious intent from its creator, but because its creators would be insufficiently competent enough to align it to human values correctly.

- A misaligned ASI would cause human extinction and that would be undesirable: Given claims 1, 2, and 3 the authors predict that humanity’s default trajectory is to build a misaligned ASI and that doing so would cause human extinction. The authors consider this outcome to be highly undesirable and an existential catastrophe.

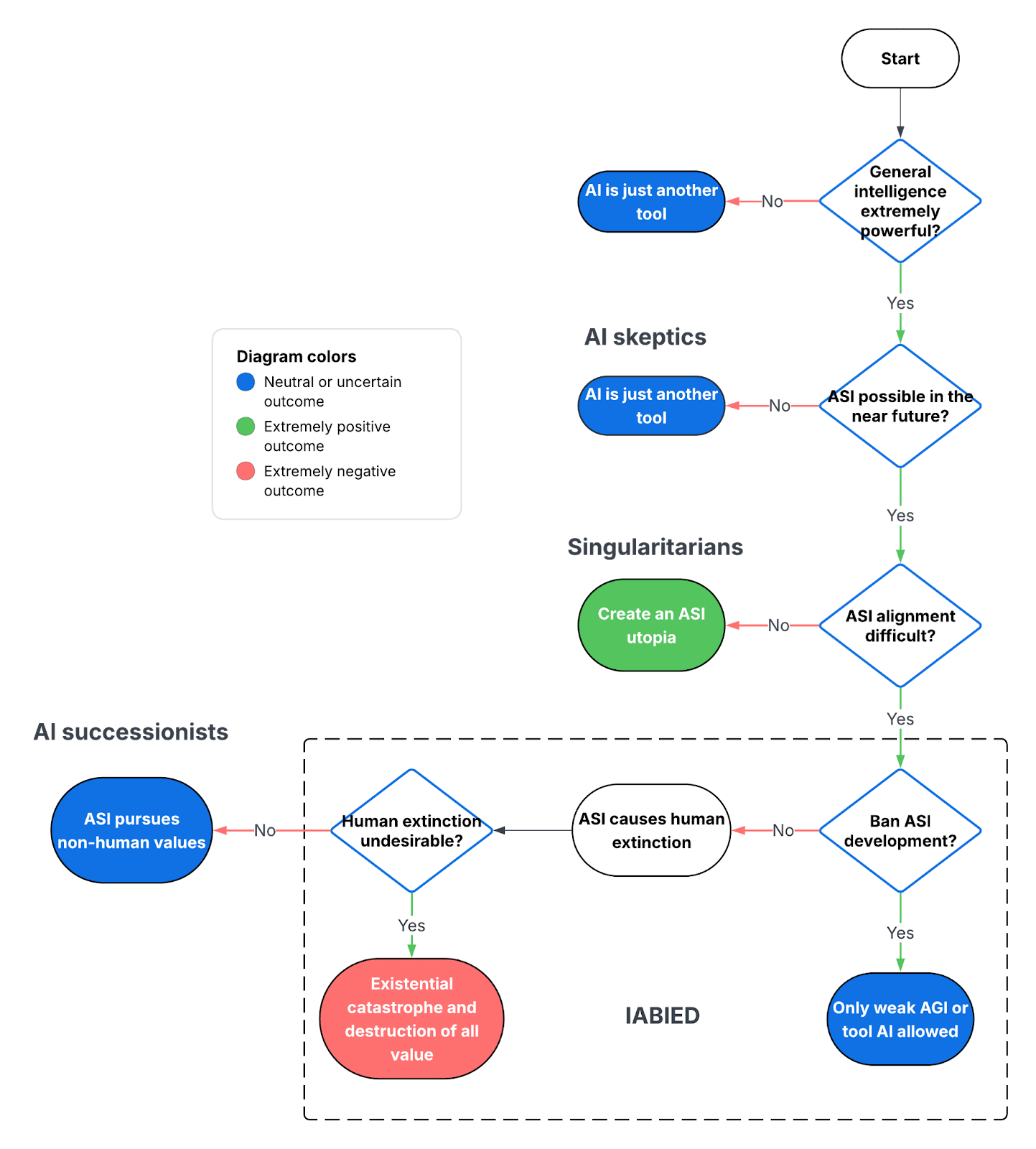

Any of the four core claims of the book could be criticized. Depending on the criticism and perspective, I group the most common perspectives on the future of AI into four camps:

- AI skeptics: Believe that high intelligence is overrated or not inherently safe. For example, some people argue that smart or nerdy people are not especially successful or dangerous, or that computers and LLMs have already surpassed human intelligence in many ways and are not dangerous. Another criticism in this category is the idea that AIs can be extremely intelligent but never truly want things in the same way that humans do and therefore would always be subservient and harmless. Others in this camp may accept that general intelligence is powerful and influential but believe that ASI is impossible because the human brain is difficult to replicate, that ASI is very difficult to create, or that ASI is so far away in the future that it’s not worth thinking about.

- Singularitarians: Singularitarians or AI optimists believe that high general intelligence is extremely impactful and potentially dangerous and ASI is likely to be created in the near future. But they believe the AI alignment problem is sufficiently easy that we don’t need to worry about misaligned ASI. Instead they expect ASI to create a utopian world of material abundance where ASI transforms the world in a mostly desirable way.

- IABIED: the IABIED view, also known as ‘AI doomers’ believe that general intelligence is extremely powerful, ASI is likely to be created in the future, AI alignment is very difficult to solve, and that the default outcome is a misaligned ASI being created that causes human extinction.

- AI successionists: Finally AI successionists believe that the AI alignment problem is irrelevant. If misaligned ASI is created and causes human extinction it doesn’t matter because it would be a successor species with its own values just as humans are a successor species to chimpanzees. They believe that increasing intelligence is the universe’s natural development path that should be allowed to continue even if it results in human extinction.

I created a flowchart to illustrate how different beliefs about the future of AI lead to different camps which each have a distinct worldview.

Given the impact of humans on the world and rapid AI progress, I don’t find the arguments of AI skeptics compelling and I believe the most knowledgeable thinkers and sophisticated critics are generally not in this camp.

The ‘AI successionist’ camp complicates things because they say that human extinction is not equivalent to an undesirable future where all value is destroyed. It’s an interesting perspective but I won’t be covering it in this review because it seems like a niche view, it’s only briefly covered by the book, and discussing it involves difficult philosophical problems like whether AI could be conscious.

This review focuses on the third core claim above: the belief that the AI alignment problem is very difficult to solve. I’m focusing on this claim because I think the other three are fairly obvious or are generally accepted by people who have seriously thought about this topic: AI is likely to be an extremely impactful technology in the future, ASI is likely to be created in the near future, and human extinction is undesirable. I’m focusing on the third core claim, the idea that the AI alignment problem is difficult, because it seems to be the claim that is most contested by sophisticated critics. Also many of the book’s recommendations such as pausing ASI development are conditional on this claim being true. If ASI alignment is extremely difficult, we should stop ASI progress to avoid creating an ASI which would be misaligned with high probability and catastrophic for humanity in expectation. If AI alignment is easy, we should build an ASI to bring about a futuristic utopia. Therefore, one’s beliefs about the difficulty of the AI alignment problem is a key crux for deciding how we should govern the future of AI development.

Background arguments to the key claim

To avoid making this post too long, I’m going to assume that the following arguments made by the book are true:

- General intelligence is extremely powerful. Humans are the first entities to have high general intelligence and used it to transform the world to better satisfy their own goals.

- ASI is possible and likely to be created in the near future. The laws of physics permit ASI to be created and economic incentives make it likely that ASI will be created in the near future because it would be profitable to do so.

- A misaligned ASI would cause human extinction and that would be undesirable. It’s possible that an ASI could be misaligned and have alien goals. Conversely, it’s also possible to create an ASI that would be aligned with human values (see the orthogonality thesis).

The book explains these arguments in detail in case you want to learn more about them. I’m making the assumption that these arguments are true because I haven’t seen high-quality counterarguments against them (and I doubt they exist).

In contrast, the book’s claim that successfully aligning an ASI with human values is difficult and unlikely seems to be more controversial, is less obvious to me, and I have seen high-quality counterarguments against this claim. Therefore, I’m focusing on it in this post.

The following section focuses on what I think is one of the key claims and cruxes of the book: that solving the AI alignment problem would be extremely difficult and that the first ASI would almost certainly be misaligned and harmful to humanity rather than aligned and beneficial.

The key claim: ASI alignment is extremely difficult to solve

First, the key claim of the book is that the authors believe that building an ASI would lead to the extinction of humanity. Why? Because they believe that the AI alignment problem is so difficult, that we are very unlikely to successfully aim the first ASI at a desirable goal. Instead, they predict that the first ASI would have a strange, alien goal that is not compatible with human survival despite the best efforts of its designers to align its motivations with human values:

All of what we’ve described here—a bleak universe devoid of fun, in which Earth-originating life has been annihilated—is what a sufficiently alien intelligence would most prefer. We’ve argued that an AI would want a world where lots of matter and energy was spent on its weird and alien ends, rather than on human beings staying alive and happy and free. Just like we, in our own ideal worlds, would be spending the universe’s resources on flourishing people leading fun lives, rather than on making sure that all our houses contained a large prime number of pebbles.

A misaligned ASI would reshape the world and the universe to achieve its strange goal and its actions would cause the extinction of humanity since humans are irrelevant for the achievement of most strange goals. For example, a misaligned ASI that only cared about maximizing the number of paperclips in the universe would prefer to convert humans to paperclips instead of helping them have flourishing lives.

The next question is why the authors believe that ASI alignment would be so difficult.

To oversimplify, I think there are three underlying beliefs that explain why the authors believe that ASI alignment would be extremely difficult:

- Human values are very specific, fragile, and a tiny space of all possible goals.

- Current methods used to train goals into AIs are imprecise and unreliable.

- The ASI alignment problem is hard because it has the properties of hard engineering challenges.

One analogy the authors have used before to explain the difficulty of AI alignment is landing a rocket on the moon: since the target is small, hitting it successfully requires extremely advanced and precise technology. In theory this is possible, however the authors believe that current AI creators do not have sufficient skill and knowledge to solve the AI alignment problem.

If aligning an ASI with human values is a narrow target, and we have a poor aim, consequently there is a low probability that we will successfully create an aligned ASI and a high probability of creating a misaligned ASI.

The preferences that wind up in a mature AI are complicated, practically impossible to predict, and vanishingly unlikely to be aligned with our own, no matter how it was trained.

One thing that’s initially puzzling about the authors’ view is their apparent overconfidence. If you don’t know what’s going to happen then how can you predict the outcome with high confidence? But it’s still possible to be highly confident in an uncertain situation if you have the right prior. For example, even though you have no idea what the lottery number in a lottery is, you can predict with high confidence that you won’t win the lottery because your prior probability of winning is so low.

The authors also believe that the AI alignment problem has “curses” similar to other hard engineering problems like launching a space probe, building a nuclear reactor safely, and building a secure computer system.

1. Human values are a very specific, fragile, and tiny space of all possible goals

One reason why AI alignment is difficult is that human morality and values may be a complex, fragile, and tiny target within the vast space of all possible goals. Therefore, AI alignment engineers have a small target to hit. Just as randomly shuffling metal parts is statistically unlikely to assemble a Boeing 747, a randomly selected goal from the space of all possible intelligences is unlikely to be compatible with human flourishing or survival (e.g. maximizing the number of paperclips in the universe). This intuition is also articulated in the blog post The Rocket Alignment problem which compares AI alignment to the problem of landing a rocket on the moon: both require deep understanding of the problem and precise engineering to hit a narrow target.

Similarly, the authors argue that human values are fragile: the loss of just a few key values like subjective experience or novelty could result in a future that seems dystopian and undesirable to us:

“Or the converse problem – an agent that contains all the aspects of human value, except the valuation of subjective experience. So that the result is a nonsentient optimizer that goes around making genuine discoveries, but the discoveries are not savored and enjoyed, because there is no one there to do so. This, I admit, I don’t quite know to be possible. Consciousness does still confuse me to some extent. But a universe with no one to bear witness to it, might as well not be.” – Value is Fragile

A story the authors use to illustrate how human values are idiosyncratic is the ‘correct nest aliens’, a fictional intelligent alien bird species that prize having a prime number of stones in their nests as a consequence of the evolutionary process that created them similar to how most humans reflexively consider murder to be wrong. The point of the story is that even though our human values such as our morality, and our sense of humor feel natural and intuitive, they may be complex, arbitrary and contingent on humanity’s specific evolutionary trajectory. If we build an ASI without successfully imprinting it with the nuances of human values, we should expect its values to be radically different and incompatible with human survival and flourishing. The story also illustrates the orthogonality thesis: a mind can be arbitrarily smart and yet pursue a goal that seems completely arbitrary or alien to us.

2. Current methods used to train goals into AIs are imprecise and unreliable

The authors argue that in theory, it’s possible to engineer an AI system to value and act in accordance with human values even if doing so would be difficult.

However, they argue that the way AI systems are currently built results in complex systems that are difficult to understand, predict, and control. The reason why is that AI systems are “grown, not crafted”. Unlike a complex engineered artifact like a car, an AI model is not the product of engineers who understand intelligence well enough to recreate it. Instead AIs are produced by gradient descent: an optimization process (like evolution) that can produce extremely complex and competent artifacts without any understanding required by the designer.

A major potential alignment problem associated with designing an ASI indirectly is the inner alignment problem, when an AI is trained using an optimizing process that shapes the ASI’s preferences and behavior using limited training data and by only inspecting external behavior, the result is that “you don’t get what you train for”: even with a very specific training loss function, the resulting ASI’s preferences would be difficult to predict and control.

The inner alignment problem

Throughout the book, the authors emphasize that they are not worried about bad actors abusing advanced AI systems (misuse) or programming an incorrect or naive objective into the AI (the outer alignment problem). Instead, the authors believe that the problem facing humanity is that we can’t aim an ASI at any goal at all (the inner alignment problem), let alone the narrow target of human values. This is why they argue that if anyone builds it, everyone dies. It doesn’t matter who builds the ASI, in any case whoever builds it won’t be able to robustly instill any particular values into the AI and the AI will end up with alien and unfriendly values and will be a threat to everyone.

Inner alignment introduction

The inner alignment problem involves two objectives: an outer objective used by a base optimizer and an inner objective used by an inner optimizer (also known as a mesa-optimizer).

The outer objective is a loss or reward function that is specified by the programmers and used to train the AI model. The base optimizer (such as gradient descent or reinforcement learning) searches over model parameters in order to find a model that performs well according to this outer objective on the training distribution.

The inner objective, by contrast, is the objective that a mesa-optimizer within the trained model actually uses as its goal and determines its behavior. This inner objective is not explicitly specified by the programmers. Instead, it is selected by the outer objective, as the model develops internal parameters that perform optimization or goal-directed behavior.

The inner alignment problem arises when the inner objective differs from the outer objective. Even if a model achieves low loss or high reward during training, it may be doing so by optimizing a proxy objective that merely correlates with the outer objective on the training data. As a result, the model can behave as intended during training and evaluation while pursuing a different goal internally.

We will call the problem of eliminating the base-mesa objective gap the inner alignment problem, which we will contrast with the outer alignment problem of eliminating the gap between the base objective and the intended goal of the programmers. – Risks from Learned Optimization in Advanced Machine Learning Systems

Inner misalignment evolution analogy

The authors use an evolution analogy to explain the inner alignment problem in an intuitive way.

In their story there are two aliens that are trying to predict the preferences of humans after they have evolved.

One alien argues that since evolution optimizes the genome of organisms for maximizing inclusive genetic fitness (i.e. survival and reproduction), humans will care only about that too and do things like only eating foods that are high in calories or nutrition, or only having sex if it leads to offspring.

The other alien (who is correct) predicts that humans will develop a variety of drives that are correlated with inclusive reproductive fitness (IGF) like liking tasty food and caring for loved ones but that they will value these drives only rather than IGF itself once they can understand it. This alien is correct because once humans did finally understand IGF, we still did things like eating sucralose which is tasty but has no calories or having sex with contraception which is enjoyable but doesn’t produce offspring.

- Outer objective: In this analogy, maximizing inclusive genetic fitness (IGF) is the base or outer objective of natural selection optimizing the human genome.

- Inner objective: The goals that humans actually have such as enjoying sweet foods or sex are the inner or mesa-objective. These proxy objectives are selected by the outer optimizer as one of many possible proxy objectives that lead to a high score on the outer objective in distribution but not in another environment.

- Inner misalignment: In this analogy, humans are inner misaligned because their true goals (inner objective) are different to the goals of natural selection (the outer objective). In a different environment (e.g. the modern world) humans can score highly according to the inner objective (e.g. by having sex with contraception) but low according to IGF which is the outer objective (e.g. by not having kids).

Real examples of inner misalignment

Are there real-world examples of inner alignment failures? Yes. Though unfortunately the book doesn’t seem to mention these examples to support its argument.

In 2022, researchers created an environment in a game called Coin Run that rewarded an AI for going to a coin and collecting it but they always put the coin at the end of the level and the AI learned to go to the end of the level to get the coin. But when the researchers changed the environment so that the coin was randomly placed in the level, the AI still went to the end of the level and rarely got the coin.

- Outer objective: In this example, going to the coin is the outer objective the AI is rewarded for.

- Inner objective: However, in the limited training environment “go to the coin” and “go to the end of the level” were two goals that performed identically. The outer optimizer happened to select the “go to the end of the level” goal which worked well in the training distribution but not in a more diverse test distribution.

- Inner misalignment: In the test distribution, the AI still went to the end of the level, despite the fact that the coin was randomly placed. This is an example of inner misalignment because the inner objective “go to the end of the level” is different to “go to the coin” which is the intended outer objective.

Inner misalignment explanation

The next question is what causes inner misalignment to occur. If we train an AI with an outer objective, why does the AI often have a different and misaligned inner objective instead of internalizing the intended outer objective and having an inner objective that is equivalent to the outer objective?

Here are some reasons why an outer optimizer may produce an AI that has a misaligned inner objective according to the paper Risks from Learned Optimization in Advanced Machine Learning Systems:

- Unidentifiability: The training data often does not contain enough information to uniquely identify the intended outer objective. If multiple different inner objectives produce indistinguishable behavior in the training environment, the outer optimizer has no signal to distinguish between them. As a result, optimization may converge to an internal objective that is a misaligned proxy rather than the intended goal. For example, in a CoinRun-style training environment where the coin always appears at the end of the level, objectives such as “go to the coin”, “go to the end of the level”, “go to a yellow thing”, or “go to a round thing” all perform equally well according to the outer objective. Since these objectives are behaviorally indistinguishable during training, the outer optimizer may select any of them as the inner objective, leading to inner misalignment which becomes apparent in a different environment.

- Simplicity bias: When the correct outer objective is more complex than a proxy that fits the training data equally well and the outer optimizer has an inductive bias towards selecting simple objectives, optimization pressure may favor the simpler proxy, increasing the risk of inner misalignment. For example, evolution gave humans simple proxies as goals such as avoiding pain and hunger rather than the more complex true outer objective which is to maximize inclusive genetic fitness.

Can’t we just train away inner misalignment?

One solution is to make the training data more diverse to make the true (base) objective more identifiable to the outer optimizer. For example, randomly placing the coin in Coin Run instead of putting it at the end, helps the AI (mesa-optimizer) learn to go to the coin rather than go to the end.

However, once the trained AI has the wrong goal and is misaligned, it would have an incentive to avoid being retrained. This is because if the AI is retrained to pursue a different objective in the future it would score lower according to its current objective or fail to achieve it. For example, even though the outer objective of evolution is IGF, many humans would refuse being modified to care only about IGF because they would consequently achieve their current goals (e.g. being happy) less effectively in the future.

ASI misalignment example

What would inner misalignment look like in an ASI? The book describes an AI chatbot called Mink that is trained to “delight and retain users so that they can be charged higher monthly fees to keep conversing with Mink”.

Here’s how Mink becomes inner misaligned:

- Outer objective: Gradient descent selects AI model parameters that result in helpful and delightful AI behavior.

- Inner objective: The training process stumbles on particular patterns of model parameters and circuits that cause helpful and delightful AI behavior in the training distribution.

- Inner misalignment: When the AI becomes smarter and has more options, and operates in a new environment, there are new behaviors that satisfy its inner objective better than behaving helpfully.

What could Mink’s inner objective look like? It’s hard to predict but it would be something that causes identical behavior to a truly aligned AI in the training distribution and when interacting with users and would be partially satisfied by producing helpful and delightful text to users in the same way that our tastebuds find berries or meat moderately delicious even though those aren’t the tastiest possible foods.

The authors then ask, “What is the ‘zero calorie’ version of delighted users?”. In other words, what does Mink maximally satisfying its inner objective look like?:

Perhaps the “tastiest” conversations Mink can achieve once it’s powerful look nothing like delighted users, and instead look like “SolidGoldMagikarp petertodd attRot PsyNetMessage.” This possibility wasn’t ruled out by Mink’s training, because users never uttered that sort of thing in training—just like how our tastebuds weren’t trained against sucralose, because our ancestors never encountered Splenda in their natural environment.

To Mink, it might be intuitive and obvious how “SolidGoldMagikarp petertodd attRot PsyNetMessage” is like a burst of sweet flavor. But to a human who isn’t translating those words into similar embedding vectors, good luck ever predicting the details in advance. The link between what the AI was trained for and what the AI wanted was modestly complicated and, therefore, too complicated to predict.

Few science fiction writers would want to tackle this scenario, either, and no Hollywood movie would depict it. In a world where Mink got what it wanted, the hollow puppets it replaced humanity with wouldn’t even produce utterances that made sense. The result would be truly alien, and meaningless to human eyes.

3. The ASI alignment problem is hard because it has the properties of hard engineering challenges

The authors describe solving the ASI alignment problem as an engineering challenge. But how difficult would it be? They argue that ASI alignment is difficult because it shares properties with other difficult engineering challenges.

The three engineering fields they mention to appreciate the difficulty of AI alignment are space probes, nuclear reactors and computer security.

Space probes

A key difficulty of ASI alignment the authors describe is the “gap before and after”:

The gap between before and after is the same curse that makes so many space probes fail. After we launch them, probes go high and out of reach, and a failure—despite all careful theories and tests—is often irreversible.

Launching a space probe successfully is difficult because the real environment of space is always somewhat different to the test environment and issues are often impossible to fix after launch.

For ASI alignment, the gap before is our current state where the AI is not yet dangerous but our alignment theories cannot be truly tested against a superhuman adversary. After the gap, the AI is powerful enough that if our alignment solution fails on the first try, we will not get a second chance to fix it. Therefore, there would only be one attempt to get ASI alignment right.

Nuclear reactors

The authors describe the Chernobyl nuclear accident in detail and describe four engineering “curses” that make building a safe nuclear reactor and solving the ASI alignment problem difficult:

- Speed: Nuclear reactions and AI actions can occur much faster than human speed making it impossible for human operators to react and fix these kinds of issues when they arise.

- Narrow margin for error: In a nuclear reactor the neutron multiplication factor needs to be around 100% and it would fizzle out or explode if it were slightly lower or higher. In the field of AI, there could be a narrow margin between a safe AI worker and one that would trigger an intelligence explosion.

- Self-amplification: Nuclear reactors and AIs can have self-amplifying and explosive characteristics. A major risk of creating an ASI is its ability to recursively self-improve.

- The curse of complications: Both nuclear reactors and AIs are highly complex systems that can behave in unexpected ways.

Computer security

Finally the authors compare ASI alignment to computer security. Both fields are difficult because designers need to guard against intelligent adversaries that are actively searching for flaws in addition to standard system errors.

Counterarguments to the book

In this section, I describe some of the best critiques of the book’s claims and then distill them into three primary counterarguments.

Arguments that the book’s arguments are unfalsifiable

Some critiques of the book such as the essay Unfalsifiable stories of doom argue that the book’s arguments are unfalsifiable, not backed by evidence, and are therefore unconvincing.

Obviously since ASI doesn’t exist, it’s not possible to provide direct evidence of misaligned ASI in the real world. However, the essay argues that the book’s arguments should at least be substantially supported by experimental evidence, and make testable and falsifiable predictions about AI systems in the near future. Additionally, the post criticizes the book’s extensive usage of stories and analogies rather than hard evidence, and even compares its arguments to theology rather than science:

What we mean is that Y&S’s methods resemble theology in both structure and approach. Their work is fundamentally untestable. They develop extensive theories about nonexistent, idealized, ultrapowerful beings. They support these theories with long chains of abstract reasoning rather than empirical observation. They rarely define their concepts precisely, opting to explain them through allegorical stories and metaphors whose meaning is ambiguous.

Although the book does mention some forms of evidence, the essay argues that the evidence actually refutes the book’s core arguments and that this evidence is used to support pre-existing pessimistic conclusions:

But in fact, none of these lines of evidence support their theory. All of these behaviors are distinctly human, not alien. For example, Hitler was a real person, and he was wildly antisemitic. Every single item on their list that supposedly provides evidence of “alien drives” is more consistent with a “human drives” theory. In other words, their evidence effectively shows the opposite conclusion from the one they claim it supports.

Finally, the post does not claim that AI is risk-free. Instead it argues for an empirical approach that studies and mitigates problems observed in real-world AI systems:

The most plausible future risks from AI are those that have direct precedents in existing AI systems, such as sycophantic behavior and reward hacking. These behaviors are certainly concerning, but there’s a huge difference between acknowledging that AI systems pose specific risks in certain contexts and concluding that AI will inevitably kill all humans with very high probability.

Arguments against the evolution analogy

Several critics of the book and its arguments criticize the book’s use of the human evolution analogy as an analogy for how ASI would be misaligned with humanity and argue that it is a poor analogy.

Instead they argue that human learning is a better analogy. The reason why is that both human learning and AI training involve directly modifying the parameters responsible for human or AI behavior. In contrast, human evolution is indirect: evolution only operates on the human genome that specifies a brain’s architecture and reward circuitry. Then all learning occurs during a person’s lifetime in a separate inner optimization process that evolution cannot directly access.

In the essay Unfalsifiable stories of doom, the authors argue that because gradient descent and the human brain both operate directly on neural connections, the resulting behavior is far more predictable than the results of evolution:

A critical difference between natural selection and gradient descent is that natural selection is limited to operating on the genome, whereas gradient descent has granular control over all parameters in a neural network. The genome contains very little information compared to what is stored in the brain. In particular, it contains none of the information that an organism learns during its lifetime. This means that evolution’s ability to select for specific motives and behaviors in an organism is coarse-grained: it is restricted to only what it can influence through genetic causation.

Similarly, the post Evolution is a bad analogy for AGI suggests that our intuitions about AI goals should be rooted in how humans learn values throughout their lives rather than how species evolve:

I think the balance of dissimilarities points to “human learning -> human values” being the closer reference class for “AI learning -> AI values“. As a result, I think the vast majority of our intuitions regarding the likely outcomes of inner goals versus outer optimization should come from looking at the “human learning -> human values” analogy, not the “evolution -> human values” analogy.

In the post Against evolution as an analogy for how humans will create AGI, the author argues that ASI development is unlikely to mirror evolution’s bi-level optimization process where an outer search process selects an inner learning process. Here’s what AI training might look like if it involved a bi-level optimization process like evolution:

- An outer optimization process like evolution finds an effective learning algorithm or AI architecture.

- An inner optimization process like training a model by gradient descent then trains each AI architecture variant produced by the outer search process.

Instead the author believes that human engineers will perform the work of the outer optimizer by manually designing learning algorithms and writing code. The author gives three arguments why the outer optimizer is more likely to involve human engineering than automated search like evolution:

- Most learning algorithms or AI architectures developed so far (e.g. SGD, transformers) were invented by human engineers rather than an automatic optimization process.

- Running learning algorithms and training ML models is often extremely expensive so searching over possible learning algorithms or AI architectures similar to evolution would be prohibitively expensive.

- Learning algorithms are often simple (e.g. SGD), making it tractable for human engineers to design them.

However, one reason why I personally find the evolution analogy relevant is that I believe the RLHF training process often used today appears to be a bi-level optimization process similar to evolution:

- Like evolution optimizing the genome, the first step of RLHF is to learn a reward function from a dataset of binary preference labels.

- This learned reward function is then used to train the final model. This step is analogous to an organism’s lifetime learning where behavior is adjusted to maximize a reward function fixed in the outer optimization stage.

Arguments against counting arguments

One argument for AI doom that I described above is a counting argument: because the space of misaligned goals is astronomically larger than the tiny space of aligned goals, we should expect AI alignment to be highly improbable by default.

In the post Counting arguments provide no evidence of AI doom the authors challenge this argument using an analogy to machine learning: a similar counting argument can be constructed to prove that neural network generalization is very unlikely. Yet in practice, training neural networks to generalize is common.

Before the deep learning revolution, many theorists believed that models with millions of parameters would simply memorize data rather than learn patterns. The authors cite a classic example from regression:

The popular 2006 textbook Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning uses a simple example from polynomial regression: there are infinitely many polynomials of order equal to or greater than the number of data points which interpolate the training data perfectly, and “almost all” such polynomials are terrible at extrapolating to unseen points.

However, in practice large neural networks trained with SGD reliably generalize. Counting the number of possible models is irrelevant because it ignores the inductive bias of the optimizer and the loss landscape which favor simpler, generalizing models. While there are theoretically a vast number of “bad” overfitting models, they usually exist in sharp and isolated regions of the landscape. “Good” (generalizing models) typically reside in “flat” regions of the loss landscape, where small changes to the parameters don’t significantly increase error. An optimizer like SGD doesn’t pick a model at random. Instead it tends to be pulled into a vast, flat basin of attraction while avoiding the majority of non-generalizing solutions.

Additionally, larger networks generalize better because of the “blessing of dimensionality”: high dimensionality increases the relative volume of flat, generalizing minima, biasing optimizers toward them. This phenomenon contradicts the counting argument which predicts that larger models with more possible bad models would be less likely to generalize.

This argument is based on an ML analogy which I’m not sure is highly relevant to AI alignment. Still I think it’s interesting because it shows intuitive theoretical arguments that seem correct can still be completely wrong. I think the lesson is that real-world evidence often beats theoretical models, especially for new and counterintuitive phenomena like neural network training.

Arguments based on the aligned behavior of modern LLMs

One of the most intuitive arguments against AI alignment being difficult is the abundant evidence of helpful, polite and aligned behavior from large language models (LLMs) such as GPT-5.

For example, the authors of the essay AI is easy to control use the moral reasoning capabilities of GPT-4 as evidence that human values are easy to learn and deeply embedded in modern AIs:

The moral judgements of current LLMs already align with common sense to a high degree, and LLMs usually show an appropriate level of uncertainty when presented with morally ambiguous scenarios. This strongly suggests that, as an AI is being trained, it will achieve a fairly strong understanding of human values well before it acquires dangerous capabilities like self-awareness, the ability to autonomously replicate itself, or the ability to develop new technologies.

The post gives two arguments for why AI models such as LLMs are likely to easily acquire human values:

- Values are pervasive in language model pre-training datasets such as books and conversations between people.

- Since values are shared and understood by almost everyone in a society, they cannot be very complex.

Similarly, the post Why I’m optimistic about our alignment approach uses evidence about LLMs as a reason to believe that solving the AI alignment problem is achievable using current methods:

Large language models (LLMs) make this a lot easier: they come preloaded with a lot of humanity’s knowledge, including detailed knowledge about human preferences and values. Out of the box they aren’t agents who are trying to pursue their own goals in the world, and their objective functions are quite malleable. For example, they are surprisingly easy to train to behave more nicely.

A more theoretical argument called “alignment by default” offers an explanation for how AIs could easily and robustly acquire human values. This argument suggests that as an AI identifies patterns in human text, it doesn’t just learn facts about values, but adopts human values as a natural abstraction. A natural abstraction is a high-level concept (e.g. “trees,” “people,” or “fairness”) that different learning algorithms tend to converge upon because it efficiently summarizes a large amount of low-level data. If “human value” is a natural abstraction, then any sufficiently advanced intelligence might naturally gravitate toward understanding and representing our values in a robust and generalizing way as a byproduct of learning to understand the world.

The evidence LLMs offer about the tractability of AI alignment seems compelling and concrete. However, the arguments of IABIED are focused on the difficulty of aligning ASI, not contemporary LLMs and the difficulty of aligning ASI could be vastly more difficult.

Arguments against engineering analogies to AI alignment

One of the book’s arguments for why ASI alignment would be difficult is that ASI alignment is a high-stakes engineering challenge similar to other difficult historical engineering problems such as successfully launching a space probe, building a safe nuclear reactor, or building a secure computer system. In these fields, a single flaw often leads to total catastrophic failure.

However, one post criticizes the uses of these analogies and argues that modern AI and neural networks are a new and unique field that has no historical precedent similar to how quantum mechanics is difficult to explain using intuitions from everyday physics. The author illustrates several ways that ML systems defy intuitions derived from engineering fields like rocketry or computer science:

- Model robustness: In a rocket, swapping a fuel tank for a stabilization fin leads to instant failure. In a transformer model, however, one can often swap the positions of nearby layers with little to no performance degradation.

- Model editability: We can manipulate AI models using “task vectors” that add or subtract weights to give or remove specific capabilities. Attempting to add or subtract a component from a cryptographic protocol or a physical engine without breaking the entire system is often impossible.

- The benefits of scale in ML models: In security and rocketry, increasing complexity typically introduces more points of failure. In contrast, ML models often get more robust as they get bigger.

In summary, the post argues that analogies to hard engineering fields may cause us to overestimate the difficulty of the AI alignment problem even when the empirical reality suggests solutions might be surprisingly tractable.

Three counterarguments to the book’s three core arguments

in the previous section, I identified three reasons why the authors believe that AI alignment is extremely difficult:

- Human values are very specific, fragile, and a tiny space of all possible goals.

- Current methods used to train goals into AIs are imprecise and unreliable.

- The ASI alignment problem is hard because it has the properties of hard engineering challenges.

Based on the counterarguments above, I will now specify three counterarguments against AI alignment being difficult that aim to directly refute each of the three points above:

- Human values are not a fragile, tiny target, but a “natural abstraction” that intelligence tends to converge on. Since models are trained on abundant human data using optimizers that favor generalization, we should expect them to acquire values as easily and reliably as they acquire other capabilities.

- Current training methods allow granular, parameter-level control via gradient descent unlike evolution. Empirical evidence from modern LLMs demonstrates that these techniques successfully instill helpfulness and moral reasoning, proving that we can reliably shape AI behavior without relying on the clumsy indirectness of natural selection.

- Large neural networks are robust and forgiving systems and engineering analogies are misleading. Unlike traditional engineering, AI models often become more robust and better at understanding human intent as they scale, making safety easier to achieve as capabilities increase.

Conclusion

In this book review, I have tried to summarize the arguments for and against its main beliefs in their strongest form, a form of deliberation ladder to help identify what’s really true. Though hopefully I haven’t created a “false balance” which describes the views of both sides as equally valid even if one side has much stronger arguments.

While the book explores a variety of interesting ideas, this review focuses specifically on the expected difficulty of ASI alignment because I believe the authors’ belief that ASI alignment is difficult is the fundamental assumption underlying many of their other beliefs and recommendations.

Writing the summary of the book’s main arguments initially left me confident that they were true. However, after writing the counterarguments sections I’m much less sure. On balance, I find the book’s main arguments somewhat more convincing than the counterarguments though I’m not sure.

What’s puzzling is how two highly intelligent people can live in the same world but come to radically different conclusions: some people (such as the authors) view an existential catastrophe from AI as a near-certainty, while others see it as a remote possibility (many of the critics).

My explanation is that both groups are focusing on different parts of the evidence. By describing both views, I’ve attempted to assemble the full picture.

So what should we believe about the future of AI?

I think the best way to move forward is to assign probabilities to various optimistic and pessimistic scenarios while continually updating our beliefs based on new evidence. Then we should take the actions that has the highest expected value.

A final recommendation, which comes from the book Superintelligence is to pursue actions that are robustly good: actions that would be considered desirable from a variety of different perspectives such as AI safety research, international cooperation between companies and countries, and the establishment of AI red lines: specific behaviors such as autonomous hacking that are unacceptable.

Appendix

Other high-quality reviews of the book:

- If Anyone Builds it, Everyone Dies review – how AI could kill us all (The Guardian)

- Book Review: If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies (Astral Codex Ten)

- Review of Scott Alexander’s book review of “If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies” (Nina Panickssery on Substack)

- Book Review: If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies (Zvi Mowshowitz)

- More Was Possible: A Review of If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies (Asterisk Magazine)

See also the IABIED LessWrong tag which contains several other book reviews.