From Spatial Navigation to Spectral Filtering

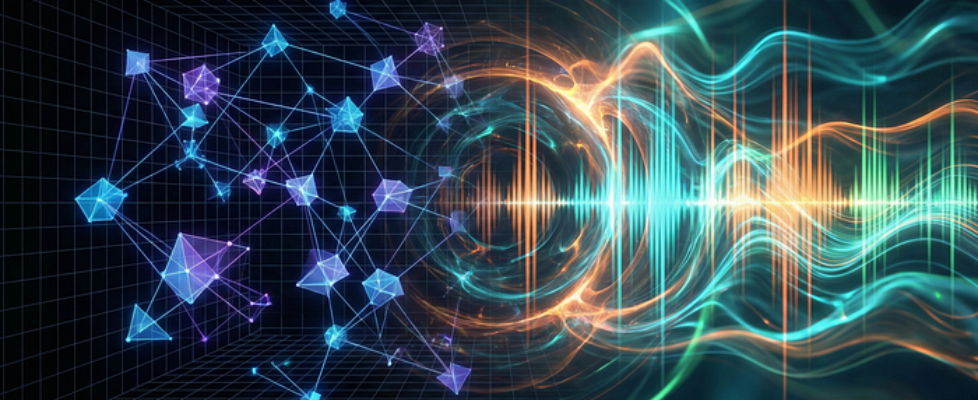

Author(s): Erez Azaria Originally published on Towards AI. Image generated by Author using AI In the world of machine learning, one of the most enigmatic and elusive concepts is “latent space”, the semantic hyperspace in which a large language model operates. Most of the time, this concept is utterly ignored or lightly defined when discussing the model operations. But what is even more surprising is that while the standard “spatial” analogy works for static embeddings, it falls short when we dive into the dynamics of inference in transformer models. The common model: A map of meaning The most abstract definition of a latent space is that it is a compressed representation of data where semantic concepts are located near each other, creating areas of semantic meaning. In this space, the location coordinates are the encoded meaning of the concept. During training, the model moves these points until similar concepts are clustered together, effectively creating a map where the distance between two points represents how related they are. The Fracture When we deal with static raw embeddings, the spatial map is very intuitive. The famous math done with Word2Vec embeddings, where the vector operation of “King”-“Man” + ”Woman” results in a location very similar to “Queen”, is appealing. The first question mark, though, arises even in the realm of static raw embeddings. Every embedding vector is essentially an arrow shooting out from the origin. It has a direction (where it points) and a magnitude (how long the arrow is). In a standard spatial map, one might assume that calculating “King” — “Man” + “Woman” moves us to the precise coordinates of “Queen”. However, in high-dimensional space, this calculation rarely lands on the exact spot. Raw embeddings have different volumes. If we compare them using standard distance, a loud vector will seem far away from a quiet one, even if they mean the same thing. But, if we force all arrows to have the same length, projecting every token onto the surface of a sphere (normalization), the spatial analogy suddenly clicks. On this spherical surface, “King” — “Man” + “Woman” and “Queen” are neighbors. Figure 1: The role of normalization in static embeddings. Raw embeddings (Left) have varying magnitudes (lengths). Only when projected onto a hypersphere (Right) do the spatial geometric relationships like “King — Man + Woman = Queen”, become intuitive. (Image generated by Author using AI) So, in order to figure out similarity between two semantic concepts, we must ignore the magnitude and look only at the direction (cosine similarity). Why we must ignore the “loudness” of the vector to find its meaning in spatial analogy remains a point of confusion for many. The Dynamics of Inference Diving into the dynamics of inference in a transformer model, two very odd phenomena emerge. A transformer model has several layers ranging from 32 in small models to more than a hundred in foundation models. Each layer has an attention block and a feed-forward network (FFN) block. The raw token embeddings enter the first layer, and every subsequent layer produces a new embedding called a “hidden state.” 1. Growing Magnitude: If we measure the magnitude of the generated embeddings vector after each transformer layer, we see that it keeps growing. (Xiong et al., 2020) 2. Directional Rigidity: If we check the cosine similarity (the direction) between each newly generated hidden state, we get a very high similarity (Often bigger than 0.9!). This means the product of every layer rarely strays from the general direction of the original embeddings vector. (Ethayarajh, 2019). The bottom line: if you try to visualize this spatially, the model travels during inference from the location of the token, moving in a general direction outward in bigger and bigger steps. Table 1: Internal states of Mistral-7B instruct during inference. Note how the Direction (Cosine Similarity) stabilizes quickly above 0.88, while the Magnitude (Volume) grows exponentially by nearly 90x. The Technical Reality vs. The Intuition The technical reason for the increasing magnitude and small angle changes is well known. The input of every sequential layer is comprised of the output of the former layer, but it also gets the raw input of the former layer added back in. This “bypass” is called the residual stream connection, formally expressed as: This mechanism was originally designed to preserve the gradient during training, ensuring that the original signal doesn’t vanish as it passes through deep layers. But the side effect is signal accumulation. However, the fact that we know the technical reason doesn’t help our intuition at all. There is nothing in this explanation that sits right with the standard spatial analogy. Where is the compounded semantic movement? If each layer produces a vector that points in the same direction as the previous layer, where is the spatial map navigation? What did the model learn? If it learned so little that the direction barely changed, how can the model infer a completely different next token? It becomes obvious that the geometric navigation analogy is not the best fit for the description of the internal mechanics of inference. If we want to understand the nature of the model inference, we ought to adopt a new mental model. Token embeddings as a spectral envelope I want to offer a different mental model, one that better captures the full phenomena observed. This model borrows from sound signal processing. The music spectrum display of a sound system has channels (frequency bars). Each channel gauges the level of signal in a narrow frequency band. In our new mental model, we describe the vector dimensions not as coordinates, but as channels. Figure 2: Visualizing embeddings as a spectral envelope. In this model, dimensions are viewed as frequency channels on a spectrum analyzer rather than coordinates in space. (Image generated by Author using AI). If you have a model with D dimensions, you can imagine a sound spectrum display of D bars. The raw embedding vector for a token is simply a specific preset of values in each of these […]