Educational Byte: How Crypto Networks Reach Consensus

When there’s authority, it’s easy to come to an agreement. Players can simply have a referee blow the whistle to signal the start of the game, and a bank can confirm balances in transactions. In crypto networks, though, there are no bank intermediaries. Players can join from anywhere in the world, bring their own computers, and join without permission.

Some of the players might know one another; most of them don’t. They’re not expected to trust each other. But the game must go on. Account balances must match, rules must be followed, and the ledger must be reliable.

This is the key reason for the internal structure of crypto networks. While from the outside, it might look like there are no arrangements to coordinate the actions of the players, there are design elements to the system that bring order to apparent chaos. In reality, there are mechanisms in place that allow the synchronization of many independent, self-organizing computers to act in unison without a central authority.

What Consensus Really Means in Crypto Networks

Consensus is the shared process a decentralized network uses to decide which transactions are valid, and in what order they appear. The system must answer the question of how to agree on which of the many copies of the ledger in a distributed system is legitimate and should be considered the default. These challenges aren’t new and are often summed up with the Byzantine Generals Problem: a thought experiment that outlines how to reach consensus when some participants may be unreliable or dishonest.

Without a general agreement, money could be lost, coins could be spent however many times, and people would lose faith in the network. These rules dictate the conditions under which system updates are accepted or rejected, and they run continuously in the background when a transaction gets added.

It’s important to note that consensus strategies in decentralized platforms have nothing to do with trust in people or companies. Instead, they’re integrated inside code that’s immutable. If users choose to play by the rules, their transactions will be recorded. If they choose to break the rules, their work will be ignored and they may be punished. Over time, this creates a shared history that most participants converge on, not because they chatted it through, but because the protocol pushes them there.

Of course, the system isn’t flawless. It’s still perfectly normal for different nodes to have different renditions of what the last or genuine version of the ledger is. The point is to achieve the same outcome in the end. Most participants will reach that outcome, and that will happen as they’re motivated to reach it by the protocol.

Blockchains and Competitive Consensus

A lot of cryptocurrencies use blockchains, which is a structure that stores transactions as batches called blocks and stores them chronologically. To determine whose transactions get added as the next valid block, these systems have competitive mechanisms that offer rewards and punishments for reaching agreements.

For instance, Proof of Work (PoW) is the method used on Bitcoin and Monero. Participants here are required to provide a certain amount of computational work, which will take some electrical energy and time (that’s crypto mining). The first user to solve a block’s cryptographic puzzle and propose the block has the right to get that block accepted, provided specific rules are adhered to. The cost of that work forces the system to defend against manipulation. This is because, to maliciously rewrite history of the blockchain, a manipulator would have to go back and repeat the work done by all the honest users in all previous blocks.

Proof of Stake (PoS), used by networks like Ethereum or Solana, switches out heavy computing for financial stakes. To participate, users have to lock up a certain number of coins (staking). The protocol selects who proposes blocks based on that stake and other parameters. If someone acts against the rules, the system may take away some portion of their locked-up coins as punishment. Instead of computing power, the cost of participating in PoS systems comes from capital investment.

Despite their differences, these approaches share a common feature: they rely on some type of intermediary (miners or “validators”) between a transaction being sent and its final approval. They do work, but they aren’t the only way to achieve consensus in a distributed system. n

DAG-Based Consensus: A Different Way to Agree

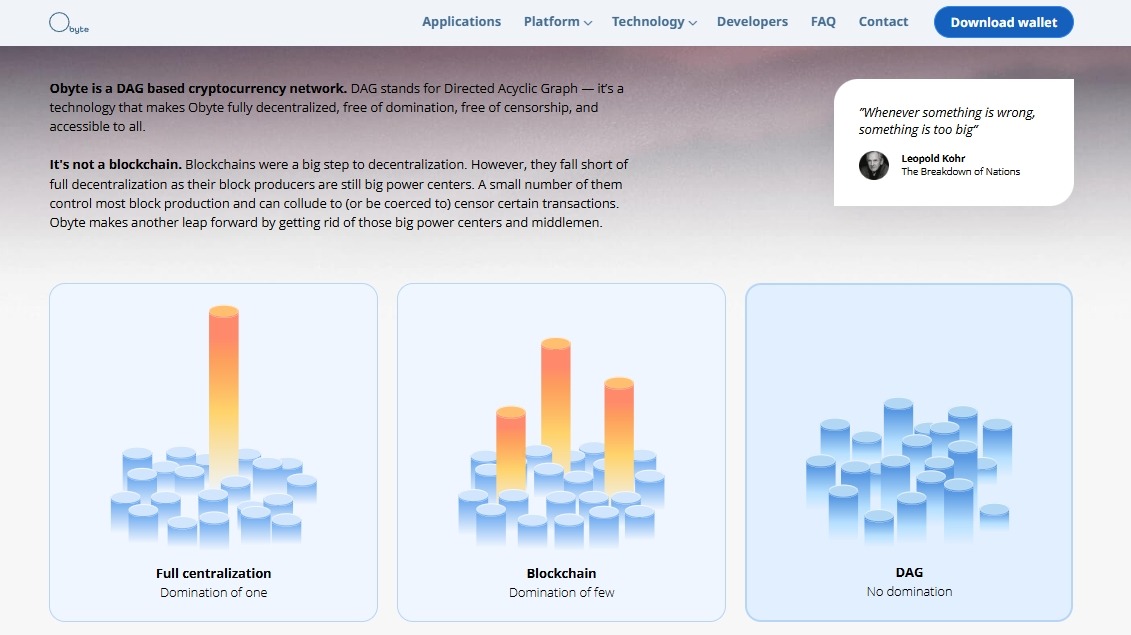

Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs) differ from blockchains in structure and consensus. Instead of forcing all transactions into a single line of blocks, it allows multiple transactions to reference each other directly at the same time. Each new transaction references a few of the older ones, creating a web rather than a chain. There’s also no energy wasted on a block race. There’s no block race at all.

Agreement emerges from following the same rules about validity and ordering of operations. A record of transactions gains stability as later transactions accumulate on top of them.Activity in the network is more distributed, and synchronicity bottlenecks from the one-at-a-time block is eliminated. Users don’t need to do anything more than transact to help stabilize the order of the previous activity. n

Obyte applies this model without miners or “validators”. Every user contributes to securing the ledger, and ordering is achieved thanks to community-voted Order Providers (OPs). They’re public nodes that periodically post transactions that act as waypoints to order the rest, but they don’t have any other power. That removes roles that can concentrate power or apply censorship. The result is a network where coordination is distributed widely and censorship becomes much harder to enforce in practice.

DAGs are rethinking how agreement forms in the first place. They’re a reminder that consensus is a design space, not a single recipe. And it can always be more decentralized.

:::info

Featured Vector Image by vector4stock / Freepik

:::

n