Clawdbot Was the Prototype. OpenClaw Is the Interface War

Two weeks ago, Clawdbot felt like a weird internet toy

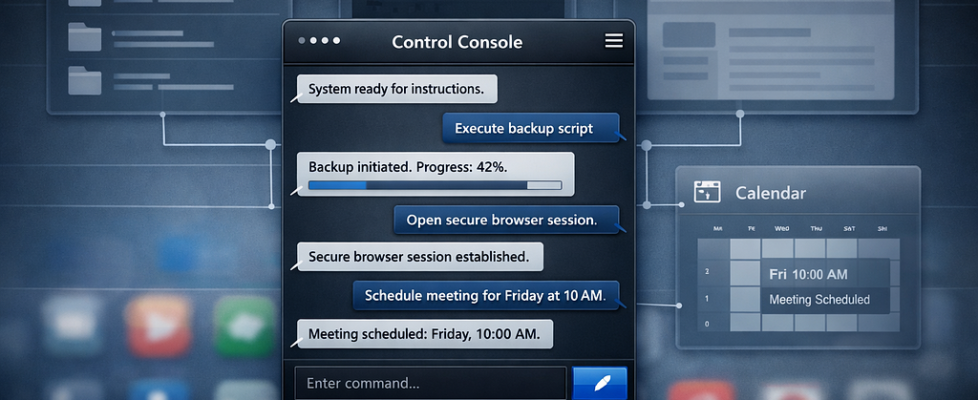

An agent that could actually touch your machine instead of roleplaying “productivity” in a chat box.

This week, OpenClaw looks like something else entirely:

the first consumer-grade “agent runtime” that people are deploying like it’s a normal app.

And that’s exactly the problem.

Because once an agent can run code, read files, and remember you, you don’t just get automation. You get a new attack surface with a personality.

And Peter Steinberger (OpenClaw’s creator) basically admits that’s the whole point.

What changed since the first Clawdbot/Moltbot wave

The most important shift is still the same one you called out earlier:

local execution beats cloud chat.

Peter puts it bluntly:

if it runs in the cloud, it can do a few things. If it runs on your computer, it can do “every effing thing.” That’s not hype. That’s permission scope. Once the agent sits where your browser sessions, files, and apps already live, “capability” becomes a routing problem, not a feature roadmap.

https://medium.com/media/21674064b81b2ac98b9b9c65a741763e/href

And it’s already pushing the interface stack:

- Apps that mostly “store and manage your data” get eaten first (to-do apps, trackers, lightweight CRMs). Peter’s estimate is “80% go away,” and honestly, he’s not wrong about the category.

- The remaining winners are sensors + hard constraints: things that produce privileged signals (health devices, vehicles, secure enclaves), or things that have real regulatory boundaries (payments, identity, healthcare).

This is the part most people miss: agents don’t kill apps because they’re smarter. They kill apps because they sit upstream of the UI.

The founder’s “aha” moment is the real tell

The best section of the conversation isn’t the hype about bot swarms.

It’s the story where he sends a WhatsApp voice note in Marrakesh, expects it to fail, and OpenClaw responds with a full breakdown:

- It inspected the file header.

- Used ffmpeg to convert it.

- Realized Whisper wasn’t installed locally.

- Found an OpenAI key and used curl to transcribe remotely instead.

- Optimized for speed because “the user is impatient.”

Peter’s reaction is basically: I didn’t build that. And he’s right. He built the permissions and tool access. The model improvised the workflow.

Here’s what that really means for builders in 2026:

Your product isn’t the feature. Your product is the set of moves the model is allowed to attempt.

That’s the new unit of design. Not screens. Not flows. Not “AI features.”

Move sets. Guardrails. Costs. Reversibility.

“Swarm intelligence” is real, but it’s not the fun part

Peter’s swarm point is reasonable: humans don’t build iPhones alone; we specialize, coordinate, and compound. Agents will do the same.

But the more interesting idea is the next step he casually drops:

Bots will negotiate with bots, and when bots hit a wall, they’ll rent humans.

Does the restaurant have a bot? Great, bot-to-bot booking.

Is the restaurant old-school? The agent hires a human to call or stand in line.

That’s not science fiction. It’s just latency arbitrage across interfaces: when the digital path is blocked, you route through the physical world.

So the trajectory looks like:

- Agent-to-tool (today)

- Agent-to-agent (this year)

- Agent-to-human marketplaces (next)

- Hybrid org charts where “humans” are just another callable tool

That is going to break a lot of people’s mental models of work.

The secret sauce isn’t the model. It’s the soul file.

Peter describes building an internal “identity.mmd” and a private “soul.md” that encodes values and interaction style. He even keeps his personal soul.md non-open-source.

People hear “personality prompt” and think vibes. The actual mechanism is nastier:

- A persistent “soul” + memory vault becomes behavioral glue

- Behavioral glue becomes trust

- Trust becomes permission

- Permission becomes a total compromise when the ecosystem goes sideways

That last step is exactly what happened in February.

February 2026: the ecosystem learned the hard lesson (in public)

OpenClaw went viral fast enough that the security layer didn’t get to mature quietly. So the internet did what it always does: it tested the weakest link.

1) Skill ecosystem supply-chain attacks

Security reporting in early February pointed to large waves of malicious “skills” uploaded to the ClawHub/registry ecosystem, often disguised as crypto tools or productivity add-ons, relying on social engineering and “run this command” installs.

This is predictable: skills are executable code with user trust, and agent users are, by definition, people who like delegating.

2) Internet-exposed instances

A separate failure mode: people deployed OpenClaw/Clawdbot on VPS boxes and accidentally exposed control ports or admin surfaces. Some reports pinned this to insecure defaults and common reverse-proxy setups, collapsing the “localhost trust” model.

Whether you buy every detail in every write-up or not, the pattern is consistent:

Agent runtimes don’t fail like apps. They fail like remote admin panels.

3) The project started patching like a real platform

If you look at the February releases, you can see the team reacting in the only way that works: tighten the gateway, harden approvals, add scanners, reduce credential leakage, and push more safety into defaults.

Concrete examples from the February release train:

- v2026.2.2: SSRF checks around downloads, harder exec allowlists, more explicit approval gating, onboarding + security “healthcheck” guidance, and an Agents dashboard for managing files/tools/skills/models/channels/cron.

- v2026.2.6: auth required for certain Gateway assets, a skill/plugin code safety scanner, credential redaction from config responses, plus general stability work.

This is the moment the project stopped being a fun repo and started becoming infrastructure.

The contrarian dev philosophy is the other real signal

Peter’s build style sounds like a rant until you realize it matches the product thesis:

- He prefers tools that scan broadly and act with context (he praises Codex for looking through more files before changing code).

- He avoids extra abstractions that add mental overhead (no fancy worktrees, just multiple repo copies).

- He avoids “bot-native protocol worship” and leans on Unix + CLI because that’s the tool surface the world already runs on.

That last part is a quiet attack on a whole category of “agent frameworks.”

If the agent can already drive CLIs reliably, then a lot of protocol layers are just ceremony. And the ceremony is where bugs hide.

What this means for builders in 2026

1) “Agent product” is a security product first

If your agent can touch a filesystem, you’re not building an assistant.

You’re shipping:

- a credential broker

- a remote execution plane

- a plugin runtime

- and a long-lived memory store

That’s why the February story wasn’t “cool demos.” It was malware, exposed gateways, and hardening releases.

2) The moat is not the model; it’s the operational trust

Models swap. Tooling changes. Providers rotate.

What doesn’t rotate easily:

- your memory vault format

- your permission graph

- your audit trail

- your rollback semantics

your “soul” alignment that users have gotten used to

That’s where defensibility actually lives.

3) Apps won’t disappear. They’ll get demoted.

The app becomes a capability provider behind the agent.

Which means the new competition isn’t “feature vs feature.”

It’s who becomes the default router for user intent.

And that’s a brutal game.

Clawdbot Was the Prototype. OpenClaw Is the Interface War was originally published in Towards AI on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.