Building a Multi-Agent Workflow for Vendor Management with Qdrant

Designing a workflow like a real operations team

While working on a product search feature, I noticed a complication. A laptop was already present in the database. But when someone searched for “notebook computer,” it didn’t show up.

I realised that keyword-based search has its limits.

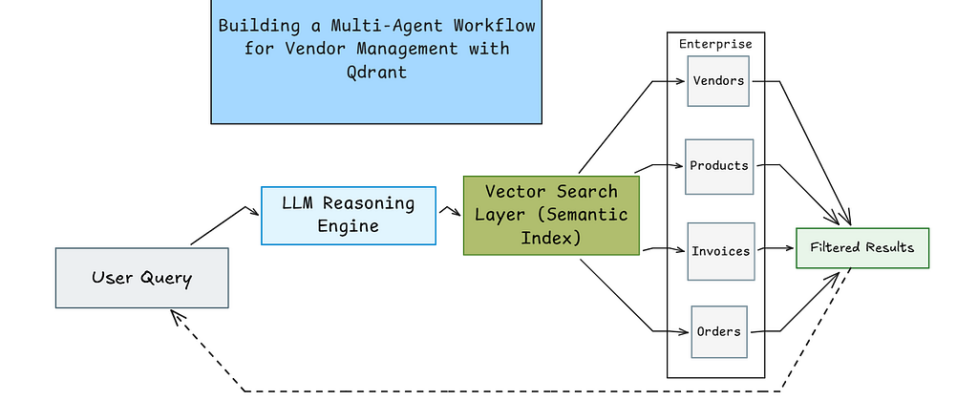

So I built a vendor management system that doesn’t depend only on exact keyword matches. It rather focuses on understanding what the user actually means.

For example, if someone searches for “laptops under $1500,” the system understands that they’re looking for products priced below $1500. It’s not just matching words but understanding meaning. The system solves three main problems that many traditional search systems struggle with.

First, it maintains clear relationships between data. Every product belongs to a vendor. Every invoice is linked to a vendor. Every order connects back to its invoice.

Second, it supports strong filtering. You can search within a price range, find unpaid invoices, or check delayed shipments.

Third, it uses an LLM to understand user intent. Instead of hardcoding specific rules. That makes it flexible enough to handle variations in keywords.

Why Qdrant?

Before going into the code, I want to explain why I chose Qdrant as the vector database for this project. When I started exploring vector databases, I first tried Pinecone and Chroma. Both are solid tools.

Pinecone is very easy to set up. You create an account, get an API key, and you’re ready to begin. For quick integration, it’s fine. But when I started adding more complex filtering logic, I personally found it less flexible than what I wanted for my use case.

Chroma is great for quick experiments, especially inside notebooks. It’s simple and works well for local development. But when I tried moving from local testing to something closer to production, I found the transition less straightforward. It required more adjustments than I’d expected.

Qdrant felt more predictable to me.

One big reason is filtering. In Qdrant, filtering isn’t just an additional feature but it’s built into how the system works. When you apply filters, the search quality does not reduce. That mattered a lot for my use case. If a user asks something specific, I need the correct results back, not something that is almost correct.

Another reason is the Python client. The way you define points and filters feels simple and structured.

There was also a practical advantage. Qdrant can run in-memory for testing or demos, and the same API works when you deploy it with Docker or in the cloud.

Let us now understand the code.

Part 1: Setting Up and Generating Realistic Data

The first step is straightforward, which is to install the required libraries and set up our environment. We need Qdrant for vector search, sentence transformers for converting text to numbers, Groq for accessing the LLaMA model, and Faker for generating realistic test data.

!pip install -q qdrant-client sentence-transformers groq langchain langchain-groq faker pandas numpy pydantic

import os

from google.colab import userdata

import json

import random

from datetime import datetime, timedelta

from typing import List, Dict, Optional, Literal

import uuid

import re

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

from faker import Faker

from pydantic import BaseModel, Field

from qdrant_client import QdrantClient

from qdrant_client.models import (

Distance, VectorParams, PointStruct,

Filter, FieldCondition, Range, MatchValue

)

from sentence_transformers import SentenceTransformer

from langchain_groq import ChatGroq

# Get API key from Colab secrets

try:

GROQ_API_KEY = userdata.get('GROQ_API_KEY')

print("API Key loaded from secrets!")

except:

GROQ_API_KEY = "your_groq_api_key_here"

print("Using hardcoded key - add to secrets for production")

os.environ["GROQ_API_KEY"] = GROQ_API_KEY

# Set random seeds for reproducible results

fake = Faker()

Faker.seed(42)

random.seed(42)

np.random.seed(42)

This code handles the imports and configuration. The important thing here is getting your Groq API key, which you can get for free from console.groq.com.

In Google Colab, you store this in the secrets manager (the key icon on the left sidebar) so it’s not exposed in your code.

Now we generate the vendor data. This is where things get interesting.

def generate_vendors(num_vendors=150):

vendors = []

categories = [

"Electronics & Computers", "Office Supplies & Stationery",

"Furniture & Fixtures", "IT Equipment & Software",

"Packaging & Shipping Materials", "Safety Equipment",

"Cleaning & Janitorial Supplies", "Industrial Tools & Equipment",

"Food & Beverages", "Textiles & Apparel"

]

for i in range(num_vendors):

vendor = {

"vendor_id": f"VND-{str(i+1).zfill(4)}",

"company_name": fake.company(),

"category": random.choice(categories),

"contact_person": fake.name(),

"email": fake.company_email(),

"phone": fake.phone_number(),

"city": fake.city(),

"state": fake.state(),

"rating": round(random.uniform(3.0, 5.0), 1),

"years_active": random.randint(1, 20),

"payment_terms": random.choice(["Net 30", "Net 60", "Net 90"]),

"is_active": random.choice([True, True, True, False])

}

vendors.append(vendor)

return vendors

vendors_data = generate_vendors(150)

print(f"Generated {len(vendors_data)} vendors")

Over here, every vendor gets a unique ID, a company name from Faker, and a category that displays what kinds of products they sell. The rating, payment terms, and active status make this more realistic.

We have made 75% of vendors active by including three True values and one False in the random choice. We try to mimic the real business data where most vendors are active but some might be inactive.

Now we will generate products that actually belong to these vendors.

def generate_products_for_vendors(vendors_data, products_per_vendor=100):

"""Generate products connected to vendors"""

all_products = []

product_id_counter = 1

product_templates = {

"Electronics & Computers": [

("Laptop", 800, 3000), ("Desktop Computer", 600, 2500),

("Monitor", 150, 800), ("Keyboard", 20, 200),

("Mouse", 10, 150), ("Webcam", 30, 300),

("Headphones", 25, 400), ("USB Cable", 5, 30),

("External Hard Drive", 60, 300), ("Graphics Card", 200, 2000)

],

"Office Supplies & Stationery": [

("Pen Set", 5, 30), ("Notebook", 3, 15),

("Stapler", 8, 25), ("Paper Clips", 2, 10),

("Folders", 4, 20), ("Printer Paper", 20, 60),

("Sticky Notes", 3, 12), ("Highlighters", 5, 18)

],

"Furniture & Fixtures": [

("Office Desk", 200, 1500), ("Office Chair", 150, 800),

("Filing Cabinet", 100, 500), ("Bookshelf", 80, 400),

("Conference Table", 500, 3000), ("Desk Lamp", 30, 150)

],

"IT Equipment & Software": [

("Router", 50, 300), ("Switch", 80, 500),

("Server", 1000, 10000), ("UPS Battery", 100, 800),

("Software License", 50, 1000), ("Antivirus Suite", 30, 200)

],

"Packaging & Shipping Materials": [

("Cardboard Box", 2, 20), ("Bubble Wrap", 15, 50),

("Packing Tape", 3, 15), ("Shipping Labels", 10, 40)

],

"Safety Equipment": [

("Hard Hat", 15, 60), ("Safety Glasses", 10, 40),

("Work Gloves", 8, 30), ("First Aid Kit", 25, 100)

],

"Cleaning & Janitorial Supplies": [

("Mop", 15, 50), ("Vacuum Cleaner", 100, 500),

("Cleaning Solution", 8, 30), ("Paper Towels", 20, 60)

],

"Industrial Tools & Equipment": [

("Power Drill", 50, 300), ("Saw", 60, 400),

("Wrench Set", 30, 150), ("Screwdriver Set", 20, 80)

],

"Food & Beverages": [

("Coffee Beans", 15, 50), ("Tea Bags", 10, 30),

("Bottled Water", 8, 25), ("Snack Bars", 12, 40)

],

"Textiles & Apparel": [

("Uniform Shirt", 20, 60), ("Safety Boots", 50, 200),

("Jacket", 40, 150), ("Cap", 10, 30)

]

}

for vendor in vendors_data:

category = vendor['category']

templates = product_templates.get(category, product_templates["Office Supplies & Stationery"])

for i in range(products_per_vendor):

template = random.choice(templates)

product_base = template[0]

min_price = template[1]

max_price = template[2]

variation = random.choice(["", "Pro", "Premium", "Standard", "Deluxe"])

product_name = f"{product_base} {variation}".strip()

product = {

"product_id": f"PRD-{str(product_id_counter).zfill(6)}",

"vendor_id": vendor['vendor_id'],

"product_name": product_name,

"category": category,

"subcategory": product_base,

"price": round(random.uniform(min_price, max_price), 2),

"stock_quantity": random.randint(0, 500),

"sku": f"SKU-{uuid.uuid4().hex[:8].upper()}",

"brand": fake.company(),

"is_available": random.choice([True, True, True, False])

}

all_products.append(product)

product_id_counter += 1

return all_products

print(" Generating 15,000 products...")

products_data = generate_products_for_vendors(vendors_data, products_per_vendor=100)

print(f" Generated {len(products_data):,} products")

The above code shows that we are not doing random data generation. We loop through each vendor and create 100 products specifically for that vendor. An electronics vendor gets laptops and monitors, an office supplies vendor gets pens and notebooks. Each product’s vendor_id field points directly to its vendor, creating a real relationship.

Also, if you see, the price ranges are realistic for each product type. Laptops cost between $800 and $3000, while pen sets range from $5 to $30. Adding variations like Pro or Premium to product names creates versatility while keeping things simple.

Now we will generate invoices.

def generate_invoices(vendors_data, products_data, num_invoices=5000):

"""Generate invoices with products from same vendor"""

invoices = []

for i in range(num_invoices):

active_vendors = [v for v in vendors_data if v['is_active']]

vendor = random.choice(active_vendors)

vendor_products = [p for p in products_data

if p['vendor_id'] == vendor['vendor_id'] and p['is_available']]

if not vendor_products:

continue

num_items = random.randint(1, min(10, len(vendor_products)))

purchased_products = random.sample(vendor_products, num_items)

line_items = []

total_amount = 0

for product in purchased_products:

quantity = random.randint(1, 20)

unit_price = product['price']

line_total = quantity * unit_price

total_amount += line_total

line_items.append({

"product_id": product['product_id'],

"product_name": product['product_name'],

"quantity": quantity,

"unit_price": unit_price,

"line_total": round(line_total, 2)

})

invoice_date = fake.date_between(start_date='-12m', end_date='today')

payment_days = {"Net 30": 30, "Net 60": 60, "Net 90": 90}.get(vendor['payment_terms'], 30)

due_date = invoice_date + timedelta(days=payment_days)

today = datetime.now().date()

if invoice_date < today - timedelta(days=payment_days+30):

status = random.choice(["Paid", "Paid", "Paid"])

payment_date = invoice_date + timedelta(days=random.randint(1, payment_days+10))

elif due_date < today:

status = random.choice(["Overdue", "Unpaid"])

payment_date = None

else:

status = random.choice(["Paid", "Unpaid", "Pending"])

payment_date = invoice_date + timedelta(days=random.randint(1, payment_days)) if status == "Paid" else None

invoice = {

"invoice_id": f"INV-{str(i+1).zfill(6)}",

"vendor_id": vendor['vendor_id'],

"invoice_date": invoice_date.strftime("%Y-%m-%d"),

"due_date": due_date.strftime("%Y-%m-%d"),

"payment_date": payment_date.strftime("%Y-%m-%d") if payment_date else None,

"status": status,

"total_amount": round(total_amount, 2),

"line_items": line_items,

"num_items": len(line_items)

}

invoices.append(invoice)

return invoices

print(" Generating 5,000 invoices...")

invoices_data = generate_invoices(vendors_data, products_data, 5000)

print(f" Generated {len(invoices_data):,} invoices")

The invoice generation shows business logic. When we create an invoice, we choose a vendor and then only select products that belong to that vendor.

Note that even the payment status logic is realistic. Old invoices are usually paid, invoices past their due date are overdue or unpaid, and recent invoices might still be pending. The due date calculation is based on every vendor’s payment terms (Net 30, Net 60, or Net 90).

Finally, we create order tracking records linked to these invoices.

def generate_order_tracking(invoices_data):

"""Generate order tracking connected to invoices"""

orders = []

statuses = ["Order Received", "Processing", "Shipped", "In Transit",

"Out for Delivery", "Delivered", "Delayed"]

carriers = ["FedEx", "UPS", "DHL", "USPS"]

for invoice in invoices_data:

if invoice['status'] not in ['Paid', 'Processing']:

continue

invoice_date = datetime.strptime(invoice['invoice_date'], "%Y-%m-%d").date()

days_since = (datetime.now().date() - invoice_date).days

if days_since > 30:

current_status = "Delivered"

elif days_since > 10:

current_status = random.choice(["Delivered", "In Transit"])

else:

current_status = random.choice(["Shipped", "In Transit", "Processing"])

if random.random() < 0.05:

current_status = "Delayed"

ship_date = invoice_date + timedelta(days=random.randint(1, 5))

expected_delivery = ship_date + timedelta(days=random.randint(3, 10))

actual_delivery = ship_date + timedelta(days=random.randint(3, 12)) if current_status == "Delivered" else None

order = {

"order_id": f"ORD-{invoice['invoice_id'].split('-')[1]}",

"invoice_id": invoice['invoice_id'],

"vendor_id": invoice['vendor_id'],

"tracking_number": f"TRK-{uuid.uuid4().hex[:12].upper()}",

"carrier": random.choice(carriers),

"current_status": current_status,

"ship_date": ship_date.strftime("%Y-%m-%d"),

"expected_delivery": expected_delivery.strftime("%Y-%m-%d"),

"actual_delivery": actual_delivery.strftime("%Y-%m-%d") if actual_delivery else None,

"origin_city": fake.city(),

"destination_city": fake.city()

}

orders.append(order)

return orders

print(" Generating order tracking...")

orders_data = generate_order_tracking(invoices_data)

print(f" Generated {len(orders_data):,} orders")

print(f"n PHASE 1 COMPLETE!")

print(f" Vendors: {len(vendors_data)}")

print(f" Products: {len(products_data):,}")

print(f" Invoices: {len(invoices_data):,}")

print(f" Orders: {len(orders_data):,}")

Orders only exist for paid or processing invoices, which makes sense. The progress of status is based upon how long ago the order was placed. Orders over 30 days ago are delivered, while recent orders would still be in transit. We add a 5% chance of delays to simulate real-world issues.

Now we have 150 vendors, 15,000 products (100 per vendor), around 5,000 invoices, and roughly 3,000 order tracking records. The entire data is interconnected due to which you can trace any product back to its vendor, any invoice to its products and vendor, and any order to its invoice.

Part 2: Building the Vector Search Database with Qdrant

Now that we have the required data, we need to store it in a way that will support both semantic search and precise filtering. This is where Qdrant comes in.

qdrant = QdrantClient(":memory:")

print(" Qdrant started")

print(" Loading embedding model...")

embedder = SentenceTransformer('all-MiniLM-L6-v2')

vector_size = 384

print(f" Model loaded (vector size: {vector_size})"

Qdrant is a vector database designed for similarity search. We will be running it in memory mode for this demo, which means the data disappears when the program ends.

Though it’s much faster than setting up a persistent database.

The sentence transformer model converts text into 384-dimensional vectors. Think of these vectors as coordinates in a 384-dimensional space where similar meanings end up near each other. When we search for a laptop, items described as computer or notebook will be nearby, even though the words are different.

Now, we will create four separate collections for our different data types.

qdrant.create_collection(

collection_name="products",

vectors_config=VectorParams(size=vector_size, distance=Distance.COSINE)

)

print(" Created 'products' collection")

qdrant.create_collection(

collection_name="vendors",

vectors_config=VectorParams(size=vector_size, distance=Distance.COSINE)

)

print(" Created 'vendors' collection")

qdrant.create_collection(

collection_name="invoices",

vectors_config=VectorParams(size=vector_size, distance=Distance.COSINE)

)

print(" Created 'invoices' collection")

qdrant.create_collection(

collection_name="orders",

vectors_config=VectorParams(size=vector_size, distance=Distance.COSINE)

)

print(" Created 'orders' collection")

Each collection uses cosine distance, which measures how similar two vectors are based on the angle between them. This works better than Euclidean distance for text embeddings.

Now comes the important part and that is uploading our data.

print("Uploading products...")

product_points = []

for idx, p in enumerate(products_data):

text = f"{p['product_name']} from {p['category']} priced at ${p['price']}"

vector = embedder.encode(text).tolist()

point = PointStruct(

id=idx,

vector=vector,

payload={

"product_id": p['product_id'],

"vendor_id": p['vendor_id'],

"product_name": p['product_name'],

"category": p['category'],

"subcategory": p['subcategory'],

"price": p['price'],

"stock_quantity": p['stock_quantity'],

"is_available": p['is_available']

}

)

product_points.append(point)

For each product, we create a text description that combines the name, category, and price. This text gets converted into a vector. But it differs from a basic vector search system in that we also store the original data fields in the payload.

The payload includes the price as a number, not just text. This means we can later filter for products where price <= 1500. Same with the vendor_id. The is_available boolean helps us understand the availability.

We do the same for vendors, invoices, and orders in the following manner

We do the same for vendors, invoices, and orders in the following manner

print("Uploading vendors...")

vendor_points = []

for idx, v in enumerate(vendors_data):

text = f"{v['company_name']} sells {v['category']} rated {v['rating']} stars"

vector = embedder.encode(text).tolist()

point = PointStruct(

id=idx,

vector=vector,

payload={

"vendor_id": v['vendor_id'],

"company_name": v['company_name'],

"category": v['category'],

"rating": v['rating'],

"city": v['city'],

"is_active": v['is_active']

}

)

vendor_points.append(point)

qdrant.upsert(collection_name="vendors", points=vendor_points)

print(f" Uploaded {len(vendor_points)} vendors")

# Upload Invoices

print("Uploading invoices...")

invoice_points = []

for idx, inv in enumerate(invoices_data):

text = f"Invoice {inv['invoice_id']} for ${inv['total_amount']} status {inv['status']}"

vector = embedder.encode(text).tolist()

point = PointStruct(

id=idx,

vector=vector,

payload={

"invoice_id": inv['invoice_id'],

"vendor_id": inv['vendor_id'],

"total_amount": inv['total_amount'],

"status": inv['status'],

"invoice_date": inv['invoice_date'],

"due_date": inv['due_date'],

"num_items": inv['num_items']

}

)

invoice_points.append(point)

qdrant.upsert(collection_name="invoices", points=invoice_points)

print(f" Uploaded {len(invoice_points):,} invoices")

# Upload Orders

print("Uploading orders...")

order_points = []

for idx, order in enumerate(orders_data):

text = f"Order {order['order_id']} via {order['carrier']} status {order['current_status']}"

vector = embedder.encode(text).tolist()

point = PointStruct(

id=idx,

vector=vector,

payload={

"order_id": order['order_id'],

"invoice_id": order['invoice_id'],

"vendor_id": order['vendor_id'],

"tracking_number": order['tracking_number'],

"carrier": order['carrier'],

"current_status": order['current_status'],

"ship_date": order['ship_date'],

"expected_delivery": order['expected_delivery']

}

)

order_points.append(point)

qdrant.upsert(collection_name="orders", points=order_points)

print(f" Uploaded {len(order_points):,} orders")

Every time the pattern is the same and that is to create a description, convert it to a vector for semantic search, but also store the structured fields for precise filtering. This gives us the best of both worlds.

Part 3: Understanding Queries with LLM

This is where things get interesting. We are not hardcoding patterns to recognize queries. We are using an LLM to actually understand what the user wants.

So first, we define the structure that we want our LLM to produce using Pydantic models.

llm = ChatGroq(

model="llama-3.1-8b-instant",

temperature=0.1,

max_tokens=1000

)

print(" LLM initialized")

# Pydantic Models for Structured Output

class PriceFilter(BaseModel):

min_price: Optional[float] = None

max_price: Optional[float] = None

class ProductQuery(BaseModel):

search_term: str

category: Optional[str] = None

vendor_id: Optional[str] = None

price_filter: Optional[PriceFilter] = None

available_only: bool = True

class VendorQuery(BaseModel):

search_term: str

category: Optional[str] = None

min_rating: Optional[float] = None

active_only: bool = True

class InvoiceQuery(BaseModel):

search_term: str

vendor_id: Optional[str] = None

status: Optional[Literal["Paid", "Unpaid", "Overdue", "Pending"]] = None

min_amount: Optional[float] = None

max_amount: Optional[float] = None

class OrderQuery(BaseModel):

search_term: str

vendor_id: Optional[str] = None

carrier: Optional[Literal["FedEx", "UPS", "DHL", "USPS"]] = None

status: Optional[str] = None

class QueryIntent(BaseModel):

query_type: Literal["product", "vendor", "invoice", "order"]

product_query: Optional[ProductQuery] = None

vendor_query: Optional[VendorQuery] = None

invoice_query: Optional[InvoiceQuery] = None

order_query: Optional[OrderQuery] = None

explanation: str

These models define exactly what information we need from different types of queries. A product query may have price filters, a vendor query may have a minimum rating, an invoice query may have a status filter.

Now we create the function that asks the LLM to parse queries.

def parse_natural_language_query(user_query: str) -> QueryIntent:

"""

Use LLM to parse query - NO HARDCODED IF-ELSE!

The LLM actually understands the query intelligently.

"""

prompt = f"""You are a query parser for a vendor management system.

Parse this user query and extract structured information:

"{user_query}"

IMPORTANT: Return ONLY a valid JSON object matching this structure:

{{

"query_type": "product|vendor|invoice|order",

"product_query": {{"search_term": "...", "price_filter": {{"min_price": X, "max_price": Y}}}},

"vendor_query": {{"search_term": "...", "min_rating": X}},

"invoice_query": {{"search_term": "...", "status": "Paid|Unpaid|Overdue", "min_amount": X}},

"order_query": {{"search_term": "...", "carrier": "FedEx|UPS|DHL|USPS", "status": "..."}},

"explanation": "brief explanation"

}}

Examples:

Query: "laptops under $1500"

{{

"query_type": "product",

"product_query": {{

"search_term": "laptops",

"price_filter": {{"max_price": 1500}},

"available_only": true

}},

"explanation": "Searching for laptops with max price $1500"

}}

Query: "unpaid invoices over $5000"

{{

"query_type": "invoice",

"invoice_query": {{

"search_term": "invoices",

"status": "Unpaid",

"min_amount": 5000

}},

"explanation": "Searching for unpaid invoices over $5000"

}}

Query: "electronics vendors rated above 4.5"

{{

"query_type": "vendor",

"vendor_query": {{

"search_term": "electronics vendors",

"category": "Electronics",

"min_rating": 4.5,

"active_only": true

}},

"explanation": "Searching for electronics vendors with rating > 4.5"

}}

Query: "delayed FedEx shipments"

{{

"query_type": "order",

"order_query": {{

"search_term": "shipments",

"carrier": "FedEx",

"status": "Delayed"

}},

"explanation": "Searching for delayed FedEx orders"

}}

Now parse: "{user_query}"

Return ONLY the JSON object, no markdown, no explanation before or after."""

try:

response = llm.invoke(prompt)

response_text = response.content.strip()

# Clean markdown if present

if response_text.startswith("```json"):

response_text = response_text.replace("```json", "").replace("```", "").strip()

elif response_text.startswith("```"):

response_text = response_text.replace("```", "").strip()

# Parse JSON

parsed_json = json.loads(response_text)

query_intent = QueryIntent(**parsed_json)

return query_intent

except Exception as e:

print(f" LLM parsing error: {e}")

print(f"Response: {response_text[:200] if 'response_text' in locals() else 'N/A'}...")

# Simple fallback

return QueryIntent(

query_type="product",

product_query=ProductQuery(search_term=user_query),

explanation="Fallback search"

)

The prompt gives the LLM examples of what we are looking for. When someone asks for laptops under $1500, we want it to understand that this is a product query with a maximum price of $1500. When they ask for unpaid invoices over $5000, we want it to understand the status filter and minimum amount.

The LLM returns JSON that we parse into our Pydantic models.

The important insight here is that we’re not using hardcoded if-else statements. The LLM actually understands that words like under, less than, cheaper than, and priced below all mean the same thing. The system can handle variations in how people ask questions.

Now we convert it into Qdrant filters.

def build_qdrant_filter(query_intent: QueryIntent) -> Optional[Filter]:

"""Build Qdrant filter from parsed query"""

conditions = []

if query_intent.query_type == "product" and query_intent.product_query:

pq = query_intent.product_query

if pq.price_filter:

if pq.price_filter.min_price is not None and pq.price_filter.max_price is not None:

conditions.append(

FieldCondition(

key="price",

range=Range(gte=pq.price_filter.min_price, lte=pq.price_filter.max_price)

)

)

elif pq.price_filter.min_price is not None:

conditions.append(FieldCondition(key="price", range=Range(gte=pq.price_filter.min_price)))

elif pq.price_filter.max_price is not None:

conditions.append(FieldCondition(key="price", range=Range(lte=pq.price_filter.max_price)))

if pq.vendor_id:

conditions.append(FieldCondition(key="vendor_id", match=MatchValue(value=pq.vendor_id)))

if pq.available_only:

conditions.append(FieldCondition(key="is_available", match=MatchValue(value=True)))

elif query_intent.query_type == "vendor" and query_intent.vendor_query:

vq = query_intent.vendor_query

if vq.min_rating is not None:

conditions.append(FieldCondition(key="rating", range=Range(gte=vq.min_rating)))

if vq.active_only:

conditions.append(FieldCondition(key="is_active", match=MatchValue(value=True)))

elif query_intent.query_type == "invoice" and query_intent.invoice_query:

iq = query_intent.invoice_query

if iq.status:

conditions.append(FieldCondition(key="status", match=MatchValue(value=iq.status)))

if iq.min_amount is not None and iq.max_amount is not None:

conditions.append(

FieldCondition(key="total_amount", range=Range(gte=iq.min_amount, lte=iq.max_amount))

)

elif iq.min_amount is not None:

conditions.append(FieldCondition(key="total_amount", range=Range(gte=iq.min_amount)))

elif iq.max_amount is not None:

conditions.append(FieldCondition(key="total_amount", range=Range(lte=iq.max_amount)))

if iq.vendor_id:

conditions.append(FieldCondition(key="vendor_id", match=MatchValue(value=iq.vendor_id)))

elif query_intent.query_type == "order" and query_intent.order_query:

oq = query_intent.order_query

if oq.status:

conditions.append(FieldCondition(key="current_status", match=MatchValue(value=oq.status)))

if oq.carrier:

conditions.append(FieldCondition(key="carrier", match=MatchValue(value=oq.carrier)))

if oq.vendor_id:

conditions.append(FieldCondition(key="vendor_id", match=MatchValue(value=oq.vendor_id)))

if conditions:

return Filter(must=conditions)

return None

This function takes the structured query and builds the actual Qdrant filter conditions.

The significance of this approach is that all the complexity of understanding natural language is handled by the LLM. This function is doing straightforward translation from our structured format to Qdrant’s filter format.

Part 4: Putting It All Together

Now we combine everything together in a single query function that handles the complete pipeline.

def smart_query(user_query: str, limit: int = 5):

"""

Complete intelligent query pipeline using LLM

NO HARDCODED IF-ELSE!

"""

print(f"n{'='*70}")

print(f" USER QUERY: {user_query}")

print(f"{'='*70}n")

# Step 1: LLM parses query

print(" Step 1: LLM parsing query...")

query_intent = parse_natural_language_query(user_query)

print(f" Type: {query_intent.query_type}")

print(f" Explanation: {query_intent.explanation}")

# Step 2: Build filter

print("n Step 2: Building Qdrant filter...")

qdrant_filter = build_qdrant_filter(query_intent)

if qdrant_filter:

print(f" Filters applied: {len(qdrant_filter.must)} conditions")

else:

print(" No filters (semantic search only)")

# Step 3: Get collection and search term

collection_map = {

"product": "products",

"vendor": "vendors",

"invoice": "invoices",

"order": "orders"

}

collection = collection_map[query_intent.query_type]

if query_intent.query_type == "product" and query_intent.product_query:

search_term = query_intent.product_query.search_term

elif query_intent.query_type == "vendor" and query_intent.vendor_query:

search_term = query_intent.vendor_query.search_term

elif query_intent.query_type == "invoice" and query_intent.invoice_query:

search_term = query_intent.invoice_query.search_term

elif query_intent.query_type == "order" and query_intent.order_query:

search_term = query_intent.order_query.search_term

else:

search_term = user_query

# Step 4: Execute search

print(f"n Step 3: Searching '{collection}'...")

query_vector = embedder.encode(search_term).tolist()

try:

results = qdrant.query_points(

collection_name=collection,

query=query_vector,

query_filter=qdrant_filter,

limit=limit

).points

except Exception as e:

print(f" Error: {e}")

results = []

# Step 5: Display results

print(f"n RESULTS: Found {len(results)} matchesn")

print("-" * 70)

if not results:

print("No results found.")

return

for i, result in enumerate(results, 1):

payload = result.payload

print(f"n{i}. ", end="")

if query_intent.query_type == "product":

print(f"{payload.get('product_name')} - ${payload.get('price'):.2f}")

print(f" Category: {payload.get('category')}")

print(f" Vendor: {payload.get('vendor_id')}")

print(f" Stock: {payload.get('stock_quantity')}")

elif query_intent.query_type == "vendor":

print(f"{payload.get('company_name')}")

print(f" Category: {payload.get('category')}")

print(f" Rating: {payload.get('rating')}")

print(f" Location: {payload.get('city')}")

elif query_intent.query_type == "invoice":

print(f"Invoice {payload.get('invoice_id')} - ${payload.get('total_amount'):,.2f}")

print(f" Status: {payload.get('status')}")

print(f" Vendor: {payload.get('vendor_id')}")

print(f" Due: {payload.get('due_date')}")

elif query_intent.query_type == "order":

print(f"Order {payload.get('order_id')} - {payload.get('current_status')}")

print(f" Carrier: {payload.get('carrier')}")

print(f" Tracking: {payload.get('tracking_number')}")

print(f" Expected: {payload.get('expected_delivery')}")

print("n" + "="*70)

print("n PHASE 3 COMPLETE!")

This function orchestrates the entire process. It takes a natural language query, asks the LLM to parse it, builds a Qdrant filter, performs the search, and formats the results.

The search combines semantic similarity with precise filtering. The vector search finds items that are semantically related to the search term, while the filters ensure they meet the specified conditions.

Let’s try with some example queries:

# Demo 1: Price filter

smart_query(“show me laptops under $1200”)

Output:

1. Laptop - $961.15 Category: Electronics & Computers Vendor: VND-0008 Stock: 91

2. Laptop Standard - $973.16 Category: Electronics & Computers Vendor: VND-0030 Stock: 238

3. Laptop - $801.39 Category: Electronics & Computers Vendor: VND-0043 Stock: 23

4. Laptop - $1048.60 Category: Electronics & Computers Vendor: VND-0043 Stock: 384

5. Laptop Deluxe - $1194.11 Category: Electronics & Computers Vendor: VND-0043 Stock: 273

# Demo 2

unpaid invoices over $10000

Output:

1. Invoice INV-001873 - $14,473.97

Status: Unpaid

Vendor: VND-0131

Due: 2026–05–05

2. Invoice INV-001189 - $11,483.40

Status: Unpaid

Vendor: VND-0003

Due: 2026–03–06

3. Invoice INV-001513 - $16,377.36

Status: Unpaid

Vendor: VND-0018

Due: 2026–05–05

4. Invoice INV-002977 - $36,098.97

Status: Unpaid

Vendor: VND-0107

Due: 2026–05–05

5. Invoice INV-001524 - $35,145.97

Status: Unpaid

Vendor: VND-0100

Due: 2026–04–05

# Demo 3

electronics vendors with rating above 4.5

Output:

1. Ruiz PLC

Category: Electronics & Computers

Rating: 4.9

Location: Lake Barry

2. Smith and Sons

Category: Electronics & Computers

Rating: 4.7

Location: Boonechester

3. Burgess-Kelly

Category: Electronics & Computers

Rating: 4.9

Location: Zacharyside

4. Gonzales-Baker

Category: Industrial Tools & Equipment

Rating: 4.8

Location: Thompsonburgh

5. Smith Group

Category: IT Equipment & Software

Rating: 4.6

Location: Lake Victoria

# Demo 4

show delayed FedEx shipments

Output:

1. Order ORD-001178 - Delayed

Carrier: FedEx

Tracking: TRK-A670174DBD89

Expected: 2026–02–10

2. Order ORD-002394 - Delayed

Carrier: FedEx

Tracking: TRK-41892DD1EE4A

Expected: 2026–02–15

3. Order ORD-002023 - Delayed

Carrier: FedEx

Tracking: TRK-37A5CAFF79C5

Expected: 2026–02–12

4. Order ORD-003374 - Delayed

Carrier: FedEx

Tracking: TRK-1C426CC17B4B

Expected: 2026–02–14

5. Order ORD-001983 - Delayed

Carrier: FedEx

Tracking: TRK-0592321AEA19

Expected: 2026–02–18

# Demo 5

I need office furniture that costs between 300 and 700 dollars

Output:

Office Desk - $668.63

Category: Furniture & Fixtures

Vendor: VND-0076

Stock: 65

2. Office Desk - $608.08

Category: Furniture & Fixtures

Vendor: VND-0014

Stock: 152

3. Office Desk - $655.28

Category: Furniture & Fixtures

Vendor: VND-0076

Stock: 480

4. Office Desk - $347.61

Category: Furniture & Fixtures

Vendor: VND-0076

Stock: 428

5. Office Desk - $679.36

Category: Furniture & Fixtures

Vendor: VND-0002

Stock: 146

Each of these queries show different capabilities. The first shows price filtering, the second combines status and amount filters, the third filters by rating, the fourth combines carrier and status, and the fifth handles a complex range query.

Why This Works

Traditional search systems are based only on exact keyword matching or simple pattern recognition. A pattern-based system might have hardcoded rules which are not efficient.

This system does better because the LLM actually understands language. It can handle variations in phrasing without any additional code.

The vector search component means the system understands semantic similarity.

The filterable fields in Qdrant mean you can combine this semantic understanding with precise conditions.

The interconnected data means the results are meaningful. When you see an invoice, you can trace it back to its vendor and see what products it contains. When you see an order, you know which invoice it’s linked to. This makes the system useful for real business operations, not just demos.

Conclusion

This project shows how AI techniques can make search systems powerful. By combining vector search for semantic understanding, LLM-based query parsing for natural language, and structured filtering for precision, we get a system that handles complex questions in an efficient way.

The key here is to maintain real data relationships rather than using random test data, storing both vectors and fields in Qdrant and using an LLM to understand intent.

You can use this architecture in many domains that are not restricted to management. Any system where we need to search through related data types with complex filtering would be benefited by this approach.

The complete code runs in Google Colab with just a free Groq API key. You can use it, modify it for your use case, and experiment with different queries.

References

• Qdrant Official Documentation — Filtering

• Qdrant — Complete Guide to Filtering in Vector Search

• Qdrant Python Client (qdrant-client)

• SentenceTransformers — all-MiniLM-L6-v2 Model

• Groq Cloud — Fast LLaMA Inference API

• LangChain Groq Integration (langchain-groq)

• Pydantic — Data Validation Library for Python

• Faker — Python Library for Generating Synthetic Data

• Qdrant vs Pinecone — Developer Comparison

Building a Multi-Agent Workflow for Vendor Management with Qdrant was originally published in Towards AI on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.