Design Principles of Deep Research: Lessons from LangChain’s OpenDeepResearch

A deep dive into the architecture, prompts, and context engineering behind building your own Deep Research system

Introduction

In February 2025, OpenAI announced its Deep Research feature, and soon after, Claude, Gemini, Perplexity, GenSpark, and others followed suit with their own versions. Deep Research has since become a standard feature, with adoption spreading widely among general users.

Deep Research has transformed tasks that previously took days of manual investigation, or the kind of research work that junior consultants at consulting firms would spend nearly a week compiling, into high-quality outputs delivered in just minutes to tens of minutes. I personally use it daily for exploring adjacent fields and researching unfamiliar industries, and I’ve reached a point where I simply cannot go back to life without Deep Research.

While general adoption of Deep Research has progressed significantly, issuing instructions through a GUI every time can become tedious. There is a growing need to integrate Deep Research directly into existing chat tools and internal applications so it can be used seamlessly within business processes. Responding to this demand, OpenAI released its Deep Research API in June 2025, and Gemini followed with its own Deep Research API in December 2025.

As data sources, vector stores, shared drives, email applications, and even MCP can now be specified. Going forward, Deep Research functionality is expected to expand beyond general research based on public information to cross-organizational use cases spanning both internal and external data.

While further expansion of Deep Research is anticipated, the term “Deep Research” encompasses a wide range of approaches. There is no single correct answer for research tasks. Each provider has its own design philosophy, and responses to the same instructions can differ dramatically. I personally run Deep Research across multiple products in parallel and compare the results.

Around 2023–2024, the novelty of the technology itself was enough, and simply deploying ChatGPT company-wide was considered a goal. However, with the rise of AI agents from 2025 onward, we have entered a phase where the real question is: “How do we generate actual business value?”

The same applies to Deep Research. What matters is not simply using the latest Deep Research tool, but designing Deep Research to match your specific use cases and the value you want to deliver.

Use cases vary by organization and workflow. For example, consider the following scenarios:

1. Speed-First — Used on the go or while commuting, so response speed is the top priority. Prefers slide-format output with key points summarized rather than detailed prose.

2. Cost-Optimized — Designed for high-frequency use across an entire department, so cost is the primary constraint, with quality being an acceptable trade-off. Simple text output is sufficient.

3. Quality-First — Used only a few times per month, but accuracy and comprehensiveness of content are paramount. Long execution times per run are acceptable, and cost is not a constraint.

4. Fact-Strict — Used as reference material for board meetings and executive briefings, so only facts backed by primary sources are included. Speculation, implications, and opinions are strictly excluded (emphasis on citations).

5. Insight-Seeking — Used for brainstorming and strategic planning, prioritizing the discovery of new perspectives and discussion points over comprehensive fact compilation. Cross-industry and international case studies are actively included.

Naturally, no single Deep Research system can satisfy all requirements. While prompts can adjust behavior to some extent, this is fundamentally a design-layer concern that includes context engineering.

Since each provider’s Deep Research is a black box, the specific implementation details are unknown. However, LangChain has published an open-source project called “OpenDeepResearch.”

While keeping an eye on the evolution of each provider’s Deep Research capabilities, those in positions driving DX and AI adoption should strive to understand the full picture of Deep Research from a deeper perspective, rather than remaining mere users. This understanding will be critical for practical application and UX design.

Having thoroughly read through the source code myself, I found the learning experience extremely valuable. In this article, I will use the above repository as a case study to summarize the key design principles of Deep Research and the key considerations for practical use.

What is OpenDeepResearch

For an overview of OpenDeepResearch, the following LangChain blog post provides an excellent introduction:

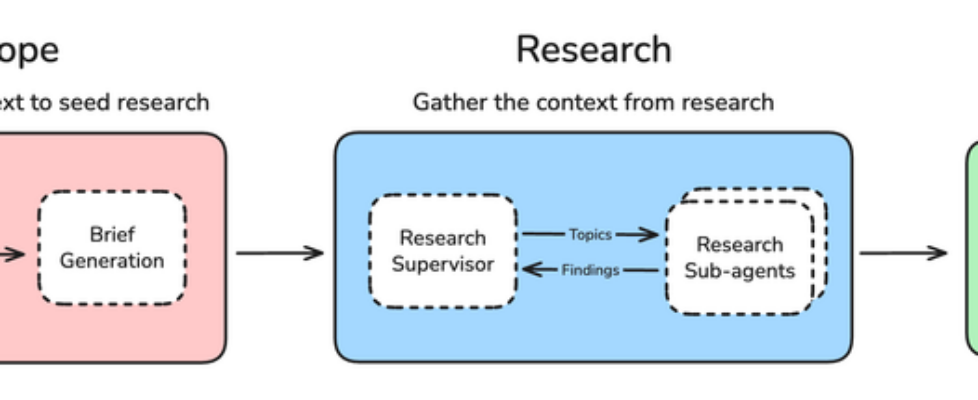

The overall flow consists of three major phases: Scope Definition, Research, and Report Generation.

Since the quality of investigation fundamentally depends on proper scope definition, a User Clarification layer is explicitly included. If there are ambiguities, the system asks the user follow-up questions iteratively.

For the Research phase, the architecture separates a Supervisor from Research sub-agents. The Supervisor generates research topics, and each sub-agent investigates its assigned topic in parallel, improving response speed while preventing context bloat.

For cases where the scope of investigation is particularly broad, increasing the maximum number of parallel sub-agents can be expected to deliver significant speedups.

Finally, there is the Report Generation module. The fact that this is labeled “One-Shot Report Generation” is a critically important design point. I personally encountered significant challenges with this in a past project, which I will discuss in detail later.

While the explanation so far might give you a sense of understanding, when you actually start thinking about “How would I implement this?”, you quickly realize there are an enormous number of design decisions to make.

If you gave this diagram to 10 engineers and asked them to implement it, you would end up with 10 different Deep Research systems, each reflecting its developer’s design philosophy.

In fact, this open-source project’s original architecture has already been deprecated, and the current architecture differs significantly. Since there is no universally correct approach to Deep Research as a task, no one can definitively say which implementation is best. Ultimately, organizations that can flexibly leverage Deep Research — adjusting breadth, depth, speed, and cost to match their use cases — will be the strongest.

While there is no universal answer, the design philosophy of LangChain’s engineers, whose approach has become near de facto in the open-source space, offers tremendous learning value. In this article, we will dive deep into the actual prompts, graphs, and state designs at the implementation level.

Overall Architecture

The repository’s README includes the following graph. When you follow the QuickStart instructions to launch a local server, this graph is displayed.

At first glance it looks straightforward, but you quickly get lost, particularly at the research_supervisor section, wondering “Where does the actual research happen?”

The diagram above only shows the first level of hierarchy. When you examine the actual code, three graph structures are defined in LangGraph:

# Main Deep Researcher Graph Construction

deep_researcher_builder = StateGraph(

AgentState,

input=AgentInputState,

config_schema=Configuration

)

# Add main workflow nodes

deep_researcher_builder.add_node("clarify_with_user", clarify_with_user)

deep_researcher_builder.add_node("write_research_brief", write_research_brief)

deep_researcher_builder.add_node("research_supervisor", supervisor_subgraph)

deep_researcher_builder.add_node("final_report_generation", final_report_generation)

# Define main workflow edges

deep_researcher_builder.add_edge(START, "clarify_with_user")

deep_researcher_builder.add_edge("research_supervisor", "final_report_generation")

deep_researcher_builder.add_edge("final_report_generation", END)

deep_researcher = deep_researcher_builder.compile()

=========================

2. Supervisor Subgraph

=========================

supervisor_builder = StateGraph(SupervisorState, config_schema=Configuration)

supervisor_builder.add_node("supervisor", supervisor)

supervisor_builder.add_node("supervisor_tools", supervisor_tools)

supervisor_builder.add_edge(START, "supervisor")

supervisor_subgraph = supervisor_builder.compile()

=========================

3. Researcher Agent Subgraph (Parallelizable)

=========================

researcher_builder = StateGraph(

ResearcherState,

output=ResearcherOutputState,

config_schema=Configuration

)

researcher_builder.add_node("researcher", researcher)

researcher_builder.add_node("researcher_tools", researcher_tools)

researcher_builder.add_node("compress_research", compress_research)

researcher_builder.add_edge(START, "researcher")

researcher_builder.add_edge("compress_research", END)

researcher_subgraph = researcher_builder.compile()

In practice, the researcher_subgraph is invoked from within supervisor_tools, where the actual research takes place. Once the supervisor determines that the responses from the research agents are sufficient, it moves to final report generation.

Looking at this alone, there is not necessarily a need to separate the supervisor into its own subgraph. Since the supervisor is called serially, it could have been expressed within the main graph directly.

However, the decision to separate it likely stems from considerations about clarifying phase boundaries, isolating state, and enabling future extensions such as replacing the supervisor itself or parallelizing it. This is one of the areas where the developers’ design philosophy is strongly evident.

Before diving into each module, let’s trace the overall processing flow along the graph.

Overall Processing Flow:

- User requests a research investigation (query) to Deep Research

- The clarify_with_user node receives the user’s query. If the research scope is clear, proceed to the next step. If it is ambiguous, return questions to the user and pause (this repeats until the research scope is clear)

- Once clarification is complete, the write_research_brief node generates a research brief (what to investigate, to what extent, and how)

- The research brief is passed to the supervisor, which generates a concrete research plan and the topics needed for investigation. Each topic is generated as an independently investigable unit

- A researcher is spawned for each topic, conducting investigation using its assigned search tools

- When investigation of the target topic is deemed sufficient, the researcher summarizes the findings and returns them to the supervisor (if insufficient, research continues iteratively)

- The supervisor reviews the findings from each topic and checks whether the content needed for report generation is covered. If sufficient, proceed; if not, conduct additional research (repeatable up to a maximum number of iterations)

- Once research is complete, the final_report_generation node generates the final report based on the research findings and returns the results to the user

By having the supervisor and each researcher operate independently, the design prevents context bloat (rather than simply accumulating research results into a shared context). Additionally, since user clarification and additional research are structured as loops, the prompt design for determining when to exit these loops is critically important. These definitions significantly affect Deep Research’s speed, cost, and report quality.

Given the multi-stage nature of this process, the importance of traceability becomes clearly apparent. When the final report falls short, you need to understand whether the problem lies in the user clarification stage (clarify_with_user), the research methodology (supervisor-research), or the report generation itself (final_report_generation). Without properly identifying the true bottleneck, your corrective actions may not lead to improvement.

In AI agents, information is generated and processed as it flows through a pipeline. While ensuring traceability through trace tools like LangSmith, you also need to properly understand the processing itself to identify where problems occur and take appropriate action.

Let’s now dive deeper into the state, prompts, and tool design at the module level.

From here on, the discussion becomes quite detailed (developer-level). If implementation details are not your focus, feel free to skip ahead to “Design Points Summary.”

Module Explanation

clarify_with_user_instructions

The first module handles confirming the research scope with the user.

In research tasks, this initial alignment with the requester is arguably the most critical step.

This applies equally to AI. When the research scope, approach, and expected output are aligned at high resolution between the requester (user) and the investigator (AI), the result is a high-quality report.

Conversely, if research proceeds with vague instructions and unclear confirmation, no matter how much time and effort the investigator puts into the report, it may prove worthless.

You have likely experienced setbacks caused by insufficient alignment, whether as a subordinate executing a task or as a manager delegating one.

The system prompt for this module is as follows:

clarify_with_user_instructions="""

These are the messages that have been exchanged so far from the

user asking for the report:

<Messages>

{messages}

</Messages>

Today's date is {date}.

Assess whether you need to ask a clarifying question, or if the

user has already provided enough information for you to start

research.

IMPORTANT: If you can see in the messages history that you have

already asked a clarifying question, you almost always do not need

to ask another one. Only ask another question if ABSOLUTELY

NECESSARY.

If there are acronyms, abbreviations, or unknown terms, ask the

user to clarify.

If you need to ask a question, follow these guidelines:

- Be concise while gathering all necessary information

- Make sure to gather all the information needed to carry out the

research task in a concise, well-structured manner.

- Use bullet points or numbered lists if appropriate for clarity.

- Don't ask for unnecessary information, or information that the

user has already provided.

Respond in valid JSON format with these exact keys:

"need_clarification": boolean,

"question": "<question to ask the user>",

"verification": "<verification message>"

"""

One interesting point right away is that today’s date is passed at the beginning of the prompt.

Naturally, the LLM itself is a snapshot from a specific point in time, so it does not know what today’s date is. If you have ever built your own AI agent application, you may have experienced the early mistake of prompting “add today’s date to the file name” only to find the file generated with an incorrect (past) date.

Since the LLM has no direct means to retrieve the current date, this information must be provided somehow. While you could pass a simple tool for retrieving the date, unless there is a need to get real-time timestamps for logging purposes, embedding it directly in the system prompt is more reasonable as it saves context consumption from tool calls.

Now to the substance of the prompt. The first thing you notice is how strongly the instructions emphasize “do not ask the same questions or ask unnecessary questions.” The relevant section being marked as “IMPORTANT” is also notable.

Obviously, most requesters find it highly frustrating to be asked the same thing repeatedly or to be asked unnecessary questions. The design leans toward broadening the user base from an accessibility standpoint. Meanwhile, the requirements for information sufficiency are kept at a relatively loose level of “sufficient for research.”

In other words, rather than being meticulously thorough in confirmation, the prompt prioritizes avoiding repeated questions at all costs and starting research once a reasonable amount of information has been gathered.

If you have used OpenAI’s Deep Research, you know that it similarly includes a step to confirm the research scope at the beginning. Opinions on this vary, but my initial impression was “Is this really enough?”

This was because after issuing a rough request, I was asked only one confirmation question, and even without a particularly detailed response, the research proceeded. In a real work situation, I would have stopped and said, “Wait, I’ve only shared a rough outline. Let’s align on the expected output before you start, to avoid rework.”

This is entirely in the realm of design, and there is no right answer; it depends on the use case. If the current priority is to introduce the concept of Deep Research within the organization, designing the system to ask many questions would discourage users from the start, so keeping it loose like this is advisable.

On the other hand, for generating reports with real business value, this level of confirmation is arguably insufficient.

For example, in research tasks, even a quick brainstorm reveals numerous confirmation points:

- Output format: Text only, chart-heavy, or a mix of both (what ratio is preferred)?

- Output volume: A one-page summary, 5–10 pages, or a comprehensive 20–30 page document?

- File format: PDF, Markdown for wiki integration, editable PPTX, or HTML for web display?

- Executive summary: Should it appear at the beginning, at the end, or not at all?

- Tone of writing: Formal report-style, reader-friendly casual tone, or should definitive statements be avoided?

- Time period: Should historical trends be considered, or is the past 10 years sufficient?

- Geographic scope: Include international case studies? Domestic only?

Output quality is entirely dependent on the requester’s expectations. There is no absolute standard of “high quality”; quality is determined by whether the output matches expectations. If someone needs a one-page Word summary for a quick internal meeting discussion, receiving a polished 30-page PowerPoint report with refined graphics and charts would actually be considered low quality.

Ideally, users would provide all such information as detailed input, but in practice, this rarely happens. While everyone acknowledges that prompt engineering is important, few people actually want to write detailed prompts. The argument “the output is bad because the input quality is low” is half-correct, but repeating this claim will only drive users away.

The key is for designers to pre-configure as much as possible, reverse-engineering from “Given this use case, what output would be best?” to ensure user input requirements are minimized. If users are accessing the system on mobile while commuting, they cannot reasonably type long, detailed prompts.

For example, if a sales department uses this for pre-meeting research, the ideal design would allow them to simply select a company name and receive the business overview and organization-specific information they need at the right level of detail. Dropdown selections for research period, analytical lens, and other parameters might also be useful.

User input effort and output quality are fundamentally a trade-off. The challenge of “How to deliver what users want while minimizing their effort” is where engineering skill shows. This is precisely why domain knowledge is considered critical in engineering. No matter how skilled you are in AI agent development, you cannot create this design without domain knowledge. Conversely, simply asking business users to “describe your use case in as much detail as possible” will only leave them confused.

To avoid becoming a case of technology-push, it is important to patiently interview business users from their perspective, show outputs early, and iterate through PDCA cycles.

From a practical standpoint, using this standard module as-is is clearly insufficient. This perspective also highlights the importance of open source — allowing you to reuse the framework while freely customizing it.

The prompt also includes the instruction “If there are acronyms, abbreviations, or unknown terms, ask the user to clarify.” While essential, having the AI ask about internal terminology every time is tedious for users. It is better to define an internal glossary in advance. If small enough, embed it in the system prompt; if large, separate it into a skill or reference that the AI can access on demand.

Keep in mind that APIs and open-source tools are published for general-purpose use and must be appropriately adapted to your specific use cases.

As for the response format of this module, it is defined in the following state:

class ClarifyWithUser(BaseModel):

"""Model for user clarification requests."""

need_clarification: bool = Field(

description="Whether the user needs to be asked a clarifying question.",

)

question: str = Field(

description="A question to ask the user to clarify the report scope",

)

verification: str = Field(

description="Verify message that we will start research.",

)

A configuration option is also provided to skip this step entirely. If sufficient information is collected at the pre-processing stage before this module — for example through application UI selections or by defining required parameters as API arguments — it is better to disable this confirmation module.

configurable = Configuration.from_runnable_config(config)

if not configurable.allow_clarification:

return Command(goto="write_research_brief")

While this module can be summarized in a single phrase as “user scope confirmation,” there are clearly numerous design considerations even at this stage.

write_research_brief

The next module creates the concrete instructions for the subsequent supervisor (research manager).

It transforms the accumulated user input and clarification exchanges into a concrete research brief.

Since this involves only LLM input/output with no tools, let’s examine the system prompt:

transform_messages_into_research_topic_prompt = """You will be

given a set of messages that have been exchanged so far between

yourself and the user. Your job is to translate these messages

into a more detailed and concrete research question that will

be used to guide the research.

Today's date is {date}.

Guidelines:

1. Maximize Specificity and Detail

- Include all known user preferences and explicitly list key

attributes or dimensions to consider.

2. Fill in Unstated But Necessary Dimensions as Open-Ended

- If certain attributes are essential but the user has not

provided them, explicitly state that they are open-ended.

3. Avoid Unwarranted Assumptions

- If the user has not provided a particular detail, do not

invent one.

4. Use the First Person

- Phrase the request from the perspective of the user.

5. Sources

- If specific sources should be prioritized, specify them.

- For product/travel research, prefer official or primary

websites rather than aggregator sites.

- For academic queries, prefer original papers rather than

secondary summaries.

"""

Guideline 1 instructs maximizing specificity and detail, with “all” emphasized repeatedly to avoid missing anything. The instruction to “explicitly list key attributes or dimensions to consider” also reveals the intent to broaden the scope from the user’s rough instructions.

Guidelines 2 and 3 further indicate that when users have not provided information (no specifications), the approach should be open-ended, with no constraints, and researchers should treat it flexibly or accept all options. This emphasis on broadening scope for comprehensiveness is what makes it “Deep” Research.

For example, if you changed this instruction to “Do not investigate anything the user has not explicitly mentioned,” the result would be a constrained, simple research agent.

For practical application, two key considerations become important:

1. Aggressively filter out unnecessary information at the instruction stage

Both a strength and weakness of Deep Research, as the prompt shows, is that it prioritizes comprehensiveness. For areas without specific instructions, it broadens the scope to avoid missing any attributes or dimensions.

While this comprehensiveness is beneficial, unnecessary scope expansion leads to increased token consumption (cost), longer response times, context pollution degrading quality, and bloated reports.

For example, if someone asks about “global population trends,” and what they actually need is post-2000 data for G7 and BRICS countries, the system might, in pursuit of comprehensiveness, begin researching nearly every country in the world from the earliest available statistics.

During application validation, you need to iterate by reviewing generated reports and processing flows, adding prompt instructions to eliminate unnecessary research.

For example, including constraints like “domestic cases only,” “within the last 3 years,” “large enterprises with 10,000+ employees only,” or “actual examples only, excluding hypothetical use cases” can improve report quality by clarifying scope. Designing what NOT to research is just as important as designing what to research.

2. Explicit specification of information sources

If there are specific sources you want prioritized, they should be specified upfront. As AI-native news sites and data sources expand, including through MCP, selecting the highest-quality data sources optimized for your use case and running Deep Research exclusively against those is an excellent approach from both quality and reliability perspectives.

More than refining the downstream research agent logic, clarifying scope and organizing information sources likely has the most direct impact on quality.

The research brief generated here is then passed to the supervisor. The key point to note is that the prior exchange history is NOT included; only the instruction prompt and the generated research brief are passed.

return Command(

goto="research_supervisor",

update={

"research_brief": response.research_brief,

"supervisor_messages": {

"type": "override",

"value": [

SystemMessage(content=supervisor_system_prompt),

HumanMessage(content=response.research_brief)

]

}

}

)

This is a critically important point for context engineering. Simply accumulating all generated information leads to context bloat. Therefore, once enough exchanges have accumulated, the content is summarized (converting user exchanges into a research brief), and only the compact summary is passed forward, preventing context bloat.

This pattern appears throughout the repository and is extremely important in AI agent design.

supervisor

Next is the supervisor. The behavior of this module is arguably the core of this Deep Research system.

An important thing to keep in mind is that the supervisor only makes decisions; all actual actions are handled by the subsequent supervisor_tools module.

Let’s look at the actual supervisor processing:

# Available tools: research delegation, completion signaling,

# and strategic thinking

lead_researcher_tools = [ConductResearch, ResearchComplete, think_tool]

research_model = (

configurable_model

.bind_tools(lead_researcher_tools)

.with_retry(stop_after_attempt=configurable.max_structured_output_retries)

.with_config(research_model_config)

)

supervisor_messages = state.get("supervisor_messages", [])

response = await research_model.ainvoke(supervisor_messages)

return Command(

goto="supervisor_tools",

update={

"supervisor_messages": [response],

"research_iterations": state.get("research_iterations", 0) + 1

}

)

Three tools are provided to the LLM: ConductResearch, ResearchComplete, and think_tool.

Let’s examine each tool definition:

class ConductResearch(BaseModel):

"""Call this tool to conduct research on a specific topic."""

research_topic: str = Field(

description="The topic to research. Should be a single

topic, described in high detail (at least a paragraph).",

)

class ResearchComplete(BaseModel):

"""Call this tool to indicate that the research is complete."""

@tool(description="Strategic reflection tool for research planning")

def think_tool(reflection: str) -> str:

"""Tool for strategic reflection on research progress.

Use this tool after each search to analyze results and plan

next steps systematically. This creates a deliberate pause

in the research workflow for quality decision-making.

When to use:

- After receiving search results

- Before deciding next steps

- When assessing research gaps

- Before concluding research

"""

return f"Reflection recorded: {reflection}"

You may have noticed something surprising: none of the tools passed here contain any actual execution logic. All actual processing is defined in supervisor_tools, and the LLM’s role here is solely to decide which tools to call.

This reflects a strong design philosophy. If tool execution logic were also written here, it would become unclear where, who, and what is being processed. Since tools are expected to be extended over time, this module is kept strictly to decision-making, with actual processing including parallelization and sub-agent implementation defined in the next module.

This design pattern of clearly separating decision-making from execution is excellent for maintainability.

Since the LLM only returns tool IDs, there is no strict requirement to write tool processing here. While you could achieve similar results with StructuredOutput, since these represent event-like actions rather than state to be maintained, defining them as tools feels more intuitive.

Let’s also examine the system prompt:

lead_researcher_prompt = """You are a research supervisor.

Your job is to conduct research by calling the "ConductResearch"

tool. For context, today's date is {date}.

<Task>

Your focus is to call the "ConductResearch" tool to conduct

research against the overall research question passed in by

the user. When you are completely satisfied with the research

findings, call the "ResearchComplete" tool.

</Task>

<Available Tools>

1. **ConductResearch**: Delegate research tasks to sub-agents

2. **ResearchComplete**: Indicate that research is complete

3. **think_tool**: For reflection and strategic planning

**CRITICAL: Use think_tool before calling ConductResearch to

plan your approach, and after each ConductResearch to assess

progress.**

</Available Tools>

<Instructions>

Think like a research manager with limited time and resources:

1. Read the question carefully

2. Decide how to delegate the research

3. After each call to ConductResearch, pause and assess

</Instructions>

<Hard Limits>

- Bias towards single agent unless clear parallelization

opportunity

- Stop when you can answer confidently

- Limit tool calls to {max_researcher_iterations}

- Maximum {max_concurrent_research_units} parallel agents

per iteration

</Hard Limits>

<Scaling Rules>

Simple fact-finding → Use 1 sub-agent

Comparisons → Use a sub-agent for each element

- Each ConductResearch call spawns a dedicated research agent

- A separate agent will write the final report

- Provide complete standalone instructions to sub-agents

</Scaling Rules>"""

This is quite intricate, so let’s break down the three tools in order.

ResearchComplete is the simplest. It is called when sufficient research results have been gathered. In supervisor_tools, calling this tool triggers the system to transition to END.

think_tool is essentially a “pause and organize” reflection tool. Since repeatedly conducting research without reflection can lead to “over-researching” that diverges from the original purpose, the design encourages constant reflection.

You might wonder, “Couldn’t this just be included in the system prompt?” However, in that case, it would be difficult to trace what was decided where and when, and as the context grows longer, the original instructions gradually weaken.

By making it a tool that is called at appropriate moments and stacking the reflection content in ToolMessages, the reflection content enters the most recent context window. This means subsequent research is informed by these reflections, enabling the investigation to proceed while constantly checking the gap between the original purpose and current progress.

This shares the same philosophy as the write_todos tool in DeepAgent. While the tool itself has no processing logic, it encourages specific thinking in the LLM, maintains traceability through history preservation, and refreshes the context.

Rather than thinking of “tool” = “concrete processing,” it may be better to think of “tool” = “action patterns you want the LLM to take, including thinking.”

ConductResearch — when called, a single research topic is passed as an argument. Each research topic spawns a research agent, with each agent operating independently and in parallel. Since conducting independent investigations serially would simply waste time, parallelization is instructed when topics can be decomposed into independent units.

However, since each agent operates independently and cannot see each other’s work, the emphasis on “only when investigations can truly proceed independently” is strongly reinforced.

To summarize the overall flow:

- think_tool to plan the investigation

- conduct_research to delegate research (sub-agents run in parallel per topic)

- (Receive research results)

- think_tool to reflect on research results

- If additional research is needed → return to step 2

- If research is sufficient → research_complete to finish

supervisor_tools

Since the supervisor only handles decisions, the actual execution is handled by supervisor_tools.

async def supervisor_tools(state, config):

# Step 1: Check exit conditions

exceeded_allowed_iterations = (

research_iterations > configurable.max_researcher_iterations

)

no_tool_calls = not most_recent_message.tool_calls

research_complete_tool_call = any(

tool_call["name"] == "ResearchComplete"

for tool_call in most_recent_message.tool_calls

)

if exceeded_allowed_iterations or no_tool_calls

or research_complete_tool_call:

return Command(goto=END, update={...})

# Step 2: Process think_tool calls

for tool_call in think_tool_calls:

reflection_content = tool_call["args"]["reflection"]

all_tool_messages.append(ToolMessage(

content=f"Reflection recorded: {reflection_content}",

name="think_tool",

tool_call_id=tool_call["id"]

))

# Step 3: Process ConductResearch calls

if conduct_research_calls:

# Limit concurrent research units

allowed = conduct_research_calls[

:configurable.max_concurrent_research_units

]

# Execute research tasks in parallel

research_tasks = [

researcher_subgraph.ainvoke({

"researcher_messages": [

HumanMessage(content=tc["args"]["research_topic"])

],

"research_topic": tc["args"]["research_topic"]

}, config)

for tc in allowed

]

tool_results = await asyncio.gather(*research_tasks)

return Command(goto="supervisor", update=update_payload)

Let’s review the key points.

Termination conditions are defined at the top. The system transitions to END if: (1) research iterations exceed the maximum, (2) no tools were called, or (3) ResearchComplete was called. Case (3) is the normal exit path, while (1) and (2) are exceptional cases.

think_tool processing: The function itself is not actually executed. Instead, the reflection content from the tool_call arguments is extracted and stacked as a ToolMessage in the context. “Passing back the results of your own thinking to yourself” might be initially confusing, but supervisor_tools should not be thought of as a subordinate. Rather, think of it as the supervisor’s own hands and feet. For think_tool specifically, imagine it as: thinking something through (supervisor) and then writing it down as a memo for yourself (supervisor_tools).

Research delegation: Creates researcher_subgraph instances for each topic, stored in a research_tasks array and then executed in parallel using gather. Each research agent processes independently without sharing context. The max_concurrent_research_units setting limits maximum concurrent execution.

researcher_subgraph

From here we enter the researcher processing. The structure mirrors the supervisor: the researcher handles decisions, researcher_tools handles execution, and compress_research consolidates results.

researcher_builder = StateGraph(

ResearcherState,

output=ResearcherOutputState,

config_schema=Configuration

)

researcher_builder.add_node("researcher", researcher)

researcher_builder.add_node("researcher_tools", researcher_tools)

researcher_builder.add_node("compress_research", compress_research)

researcher_builder.add_edge(START, "researcher")

researcher_builder.add_edge("compress_research", END)

researcher

This is the researcher’s decision node. Let’s look at the system prompt:

research_system_prompt = """You are a research assistant

conducting research on the user's input topic.

Today's date is {date}.

<Available Tools>

1. **tavily_search**: For conducting web searches

2. **think_tool**: For reflection and strategic planning

**CRITICAL: Use think_tool after each search to reflect on

results and plan next steps.**

</Available Tools>

<Instructions>

Think like a human researcher with limited time:

1. Read the question carefully

2. Start with broader searches

3. After each search, pause and assess

4. Execute narrower searches as you gather information

5. Stop when you can answer confidently

</Instructions>

<Hard Limits>

- Simple queries: 2-3 search tool calls maximum

- Complex queries: Up to 5 search tool calls maximum

- Always stop after 5 search tool calls

Stop Immediately When:

- You can answer comprehensively

- You have 3+ relevant sources

- Your last 2 searches returned similar information

</Hard Limits>"""

The available tools include: (1) think_tool (same role as in the supervisor), (2) a web search tool, and (3) MCP-related capabilities.

The web search tool is abstracted as search_api, with the configuration allowing selection from three API types: Tavily, OpenAI, and Anthropic.

class SearchAPI(Enum):

ANTHROPIC = "anthropic"

OPENAI = "openai"

TAVILY = "tavily"

NONE = "none"

This researcher’s tool definition is the most extensible point in the system. While the default is web search only, you could add tools for searching specific high-reliability site groups, vector search of internal documents, SQL queries against internal databases, and more — creating a Deep Research system that spans both internal and external information.

researcher_tools

This is where the researcher’s actual processing occurs. It simply executes all instructed tools using gather.

When ResearchComplete is called or the iteration limit is reached, processing moves to compress_research. If more research is needed, it returns to the researcher.

Now let’s look at the actual search processing — the Tavily web search implementation:

@tool(description=TAVILY_SEARCH_DESCRIPTION)

async def tavily_search(queries, max_results=5, topic="general",

config=None):

# Step 1: Execute search queries asynchronously

search_results = await tavily_search_async(

queries, max_results=max_results, topic=topic,

include_raw_content=True, config=config

)

# Step 2: Deduplicate results by URL

unique_results = {}

for response in search_results:

for result in response['results']:

url = result['url']

if url not in unique_results:

unique_results[url] = {**result, "query": response['query']}

# Step 3: Set up the summarization model

summarization_model = init_chat_model(

model=configurable.summarization_model,

max_tokens=configurable.summarization_model_max_tokens,

).with_structured_output(Summary)

# Step 4: Summarize each page in parallel

summarization_tasks = [

summarize_webpage(

summarization_model,

result['raw_content'][:max_char_to_include]

)

for result in unique_results.values()

]

summaries = await asyncio.gather(*summarization_tasks)

# Step 5: Format and return results

formatted_output = "Search results: nn"

for i, (url, result) in enumerate(summarized_results.items()):

formatted_output += f"n--- SOURCE {i+1}: {result['title']} ---n"

formatted_output += f"URL: {url}nn"

formatted_output += f"SUMMARY:n{result['content']}nn"

return formatted_output

Key insight: rather than returning raw search results directly, they are first summarized by an LLM.

The summarization function uses a StructuredOutput model that separates summary and key_excerpts:

class Summary(BaseModel):

"""Research summary with key findings."""

summary: str

key_excerpts: str

The separation of summary and key_excerpts (evidence) in the response format is particularly notable. When you want to force specific information such as citations, evidence, or metadata in the output, rather than including them in a free-text summary, it is better to explicitly separate them via StructuredOutput for stability and enforceability. Here, the StructuredOutput forces both fields to be output, and the results are combined before being returned.

compress_research

From the researcher’s perspective, this is the phase of preparing a report for the supervisor.

compress_research_system_prompt = """You are a research assistant

that has conducted research on a topic. Your job is now to clean

up the findings, but preserve all relevant information.

<Task>

You need to clean up information gathered from tool calls and

web searches. All relevant information should be preserved

verbatim, but in a cleaner format. The purpose of this step is

just to remove obviously irrelevant or duplicative information.

</Task>

<Guidelines>

1. Output should be fully comprehensive and include ALL

information gathered

2. Include inline citations for each source

3. Include a "Sources" section at the end

4. Make sure to include ALL sources

</Guidelines>

<Citation Rules>

- Assign each unique URL a single citation number

- End with ### Sources listing each source

- Number sources sequentially without gaps (1,2,3,4...)

</Citation Rules>

Critical Reminder: Preserve any relevant information verbatim.

"""

As the module name suggests, since the research results have already been summarized, this module is instructed to perform only compression, not summarization. The instructions repeatedly emphasize “the purpose of this step is just to remove obviously irrelevant or duplicative information” and “it is crucial that you don’t lose any information from the raw messages.”

Since compress_research connects to the END node, the research subgraph processing ends here. Research subgraphs run in parallel for each topic, with their report results flowing back to the supervisor.

final_report_generation

This is the final report output step. It consolidates the reports from all researchers into a final report.

final_report_generation_prompt = """Based on all the research

conducted, create a comprehensive, well-structured answer to

the overall research brief:

<Research Brief>

{research_brief}

</Research Brief>

<Messages>

{messages}

</Messages>

CRITICAL: Make sure the answer is written in the same language

as the human messages!

Today's date is {date}.

<Findings>

{findings}

</Findings>

Please create a detailed answer that:

1. Is well-organized with proper headings

2. Includes specific facts and insights

3. References relevant sources using [Title](URL) format

4. Provides a balanced, thorough analysis

5. Includes a "Sources" section at the end

<Citation Rules>

- Assign each unique URL a single citation number

- Number sources sequentially without gaps (1,2,3,4...)

- Citations are extremely important

</Citation Rules>

"""

Two important points stand out here.

First, the final report is generated in a single LLM call (one-shot). Since the final report can be quite long, you might think it would be faster to generate sections in parallel and then merge them. However, in practice this proves extremely difficult.

I have personally tried this in past projects, and the problem is that when calling the LLM independently for each section, each call produces its own “flavor” in terms of tone, sentence length, structural granularity, and so on. When combined, the result has overlapping sections, abrupt topic transitions, and an overall sense of unnaturalness.

This is analogous to the common experience of splitting a presentation on a single theme across multiple people: Person A handles pages 1–5, Person B handles pages 6–10, Person C handles pages 11–15. When merged, each section may be individually correct, but the whole feels disjointed.

This repository also initially experimented with section-by-section generation but concluded, as documented in their blog posts, that the final output should be one-shot for consistency.

Second, how you modify this prompt determines the output quality. Since this is a general-purpose open-source repository, the report generation instructions are quite generic. With vague queries and these generic instructions, the output will be a “60–70 point” report.

This is not necessarily bad, but you risk generating reports where users merely skim the listed information and think “huh, okay.” Without increasing the resolution of which output format best suits the use case, what information is impactful for the user, and what is needed right now, you end up producing reports nobody reads.

Whether the output is crafted with a clear understanding of the business context and specific personas, or whether it remains generic and inoffensive, simply reusing APIs and open source as-is will only yield “decent” reports.

While the name “Deep Research” draws attention to research depth, the most important factor is not how to build sophisticated search logic but the fundamental sharpening of the core issue.

Design Points Summary

Based on the content covered so far, let’s organize the key design principles. While Deep Research was our subject matter, these points are applicable to virtually all AI application design.

User Confirmation

In this repository, a module for confirming research content with the user is included at the very beginning.

This “user confirmation” is arguably the most critical design point in AI application development. Whether the purpose, scope, and output expectations are aligned before the AI begins its task determines more than half the outcome.

A meticulously crafted report would be considered low quality by a user who just wants a quick overview, while a neatly summarized key-points report would feel shallow to a user who wants to dive deep.

Given the importance of alignment, there are three possible approaches, with approach 3 being the goal:

Approach 1: Require users to input detailed prompts (+ educate them on prompt engineering). Technically correct but results in low adoption.

Approach 2: Make the confirmation module thorough, asking users detailed questions. Not user-friendly, as the detailed questioning creates a burden comparable to approach 1.

Approach 3: Minimize the need for user confirmation altogether. One characteristic of excellent subordinates is their ability to anticipate intent without being told everything explicitly. The design focus should not be on extracting as much information as possible from users, but on deeply understanding the user’s context and pre-configuring as much as possible.

Understanding the business, organizational structure, department usage patterns, and timing of use, you can achieve higher resolution. For example: “Typically, the past 3 years is sufficient. International cases are unnecessary; what’s needed is deep insight into regions A, B, and C. Results should be summarized in about 5 pages including diagrams for mobile reference.” Preparing several pattern variations for different personas is also a viable approach.

Data Source Specification

The quality of search results is ultimately determined by the quality of the data sources themselves. While Deep Research conjures images of broad web searches, searching a few reliable sites often produces higher quality output than broadly searching miscellaneous websites.

Improving data source quality before refining search logic is an extremely cost-effective measure. When prioritizing facts, IR materials and papers should be referenced while SNS should be prohibited. Conversely, when trend analysis is the main objective, the prompt should instruct prioritizing SNS investigation.

Narrowing data sources also provides significant benefits in response speed and token consumption (cost).

Model Selection

Rather than using the same LLM model throughout the entire process, selecting different models for different purposes can improve response performance, reduce token consumption, and enhance output quality.

OpenDeepResearch allows configuration of four different models: (1) for decision-making including research planning, (2) for summarizing web search responses, (3) for compressing research results, and (4) for generating the final report.

For example: a reasoning model for (1), a high-quality model for (4), and lightweight mini models for (2) and (3) (prioritizing speed and cost reduction).

This is admittedly an area where endless tuning is possible, and hypotheses often do not hold. Building a configuration-switching script to test combinations systematically may be the most practical approach.

Summary and Compression

The aspect I personally found most educational was the summarization and compression design.

The repository is filled with mechanisms to prevent context bloat: web search results are summarized before being returned, research agent findings are compressed to remove duplicates before returning to the supervisor, and graph states are separated so unnecessary information is not passed between phases.

Given that AI agent processing is becoming increasingly complex and longer, it will be important to consciously ask at each step: “Is unnecessary information being stacked in the context?”

StructuredOutput

When you want the LLM to output specific information, it is common to include “also output X” in the system prompt. However, system prompt instructions have no enforcement power, and the LLM occasionally “slacks off.”

Therefore, in this repository, the summary and its supporting evidence are output as separate fields:

class Summary(BaseModel):

"""Research summary with key findings."""

summary: str

key_excerpts: str

This is analogous to survey forms for humans: with a single free-text field, respondents may or may not include the information you need. But when you separate input fields for must-have information, those fields will not be left blank.

Reflection

In this case, the think_tool serves as the introspection mechanism. As research tasks grow longer, context pollution accumulates and investigations can diverge. To counter this, think_tool is provided as a tool with no actual processing, serving as a deliberate pause point.

By providing it as a tool, the LLM is constantly presented with the option to reflect, and intermediate results are organized and stacked as fresh context.

The longer the processing chain, the greater the risk that intermediate deviations compound and amplify. Explicitly designing reflection steps is likely to become increasingly important.

While model selection nuances tend to emerge naturally during development, reflection is something that will not occur to you during design unless you already know about it. This is a concept worth consciously keeping in mind.

One-Shot Final Output

A universally important principle in report generation is that while search and research processing can be parallelized, the final report must always be generated in one shot.

The temptation is to generate sections in parallel and merge them for speed. However, reports have forward and backward dependencies, and if the output tone and overall granularity are not consistent, the result is very difficult to read. When sections are generated independently, they tend to have ignored cross-references, content overlaps, inconsistent formatting, and other misalignments.

This repository also initially experimented with parallel section-by-section output but ultimately adopted one-shot generation. The lesson learned is the importance of identifying which parts should be parallelized and which absolutely should not.

Conclusion

Having read through the entire repository, my impression is that this is truly in the domain of context engineering. With the prompt content, state design, and graph separation, the number of design variables is enormous. In the absence of any absolute correct answer, the designer’s philosophy is strongly and distinctly reflected. This is precisely why context engineering is described as an art.

Conversely, the design skill of bridging what AI can do with the value an organization wants to create is what is being tested. This is arguably the most interesting challenge, and it is where product managers and architects can truly demonstrate their expertise.

While I went through the entire source code, it consists of only about 10 files and the volume itself is not overwhelming. It serves as an excellent study in LangGraph and agent design essentials, and I highly recommend it. However, there are points throughout that can be confusing (where the intent is not immediately clear), so please refer to the module explanations in Section 4 as needed.

I hope this article helps raise your resolution on AI agents, even if just a little.

Design Principles of Deep Research: Lessons from LangChain’s OpenDeepResearch was originally published in Towards AI on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.