What Actually Breaks ML Models in Production: A Fintech Case Study

Subtitle: Real production incidents from fintech classification models — and the engineering fixes that actually worked

Introduction: The Silent Failures Nobody Talks About

Your model just went live. Training metrics looked great — 0.92 AUC, precision and recall perfectly balanced. The deployment pipeline ran without a single error.

Two weeks later, your product manager sends a Slack message: “Why are we rejecting 40% more applications than last month?”

You check the monitoring dashboard. Everything shows green. The model is running. Predictions are being generated. No exceptions logged.

This is what most ML production failures actually look like.

They don’t crash. They don’t throw errors. They just quietly start making worse decisions, and by the time anyone notices, thousands of predictions have already gone wrong.

After working on multiple fintech classification models — credit risk, fraud detection, loan approvals — I’ve seen the same patterns repeat. This article documents the actual production incidents we encountered, why they were invisible to traditional monitoring, and what engineering practices actually prevented them from happening again.

These aren’t theoretical failure modes from research papers. These are real problems that cost real money and damaged real user experiences.

Failure #1: Training–Serving Skew (When Your Model Lives in Two Different Worlds)

The Incident

A credit risk model started assigning unexpectedly high risk scores to new users. Approval rates dropped by 15% over three weeks. The strange part? Our offline evaluation metrics hadn’t changed at all.

The model wasn’t broken. The features were.

What Was Really Happening

During training, we computed features using complete historical datasets. In production, we computed them using whatever data was actually available at decision time.

Consider a feature like “average transaction amount over the past 90 days”:

Training environment:

- Full transaction history available

- Feature computed from complete 90-day windows

- Missing data filled using forward-fill or interpolation

Production environment:

- Real-time feature store with 30-day retention

- New users had only 5–10 days of history

- No imputation logic at inference time

The feature had the same name in both environments. It absolutely did not have the same distribution.

The Architecture Problem

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ TRAINING PIPELINE │

│ │

│ Historical DB → Feature Engineering → Model Training │

│ (complete data) (90-day windows) (learns patterns) │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ PRODUCTION PIPELINE │

│ │

│ Feature Store → Feature Retrieval → Model Inference │

│ (30-day cache) (partial windows) (expects 90d data) │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

The model was trained on one distribution and served predictions on a completely different one.

Why Traditional Monitoring Missed It

Our monitoring tracked:

- API latency ✓

- Error rates ✓

- Prediction volume ✓

- Model version ✓

What it didn’t track:

- Feature distribution shifts

- Input data availability

- Computation path differences

The model was technically “working” — it just wasn’t working correctly.

The Code That Caused It

Offline training code:

# Training feature computation

def compute_features_offline(user_transactions_df):

"""

Uses full historical data from data warehouse

"""

features = user_transactions_df.groupby('user_id').agg({

'amount': ['mean', 'std', 'min', 'max'],

'transaction_date': 'count'

}).reset_index()

# Compute rolling statistics with full lookback

features['avg_amount_90d'] = (

user_transactions_df

.sort_values('transaction_date')

.groupby('user_id')['amount']

.rolling(window=90, min_periods=1)

.mean()

.reset_index(level=0, drop=True)

)

return features

Online inference code:

# Production feature computation

def compute_features_online(user_id, feature_store):

"""

Uses real-time feature store with limited retention

"""

# Feature store only retains 30 days

recent_txns = feature_store.get_transactions(

user_id=user_id,

days_back=30 # ← This is the problem

)

if len(recent_txns) == 0:

return default_features()

features = {

'avg_amount_90d': recent_txns['amount'].mean(), # Wrong!

'txn_count': len(recent_txns),

# ... other features

}

return features

Notice the disconnect? The training code expected 90 days. The production code could only provide 30.

What Actually Fixed It

1. Unified Feature Computation

We created a single source of truth for feature definitions:

# Shared feature library

class TransactionFeatures:

"""

Single feature definition used in both training and serving

"""

LOOKBACK_WINDOW = 30 # Explicitly defined

@staticmethod

def compute_avg_amount(transactions_df):

"""

Same logic runs in training and production

"""

if len(transactions_df) == 0:

return 0.0

# Filter to exact window used in production

cutoff_date = datetime.now() - timedelta(days=LOOKBACK_WINDOW)

recent = transactions_df[

transactions_df['transaction_date'] >= cutoff_date

]

return recent['amount'].mean() if len(recent) > 0 else 0.0

2. Feature Availability Documentation

We documented what data was actually available at inference time:

FEATURE_DEFINITIONS = {

'avg_amount_30d': {

'description': 'Average transaction amount',

'lookback_days': 30,

'availability': 'real-time',

'min_data_points': 3,

'fallback_value': 0.0

}

}

3. Training-Serving Consistency Tests

We added automated tests that compared feature distributions:

def test_feature_consistency():

"""

Verify training and serving features match

"""

# Generate features using training pipeline

training_features = compute_features_offline(sample_users)

# Generate same features using production pipeline

serving_features = [

compute_features_online(user_id, feature_store)

for user_id in sample_users

]

# Compare distributions

for feature_name in FEATURE_DEFINITIONS.keys():

train_dist = training_features[feature_name]

serve_dist = [f[feature_name] for f in serving_features]

# Statistical comparison

ks_stat, p_value = ks_2samp(train_dist, serve_dist)

assert p_value > 0.05, (

f"Feature {feature_name} distributions differ: "

f"KS statistic = {ks_stat}, p-value = {p_value}"

)

4. Feature Removal Over Feature Engineering

In several cases, we simply removed problematic features:

- Features requiring data unavailable at inference time → Removed

- Features with inconsistent computation paths → Removed

- Features that couldn’t be reliably replicated → Removed

Counterintuitively, removing features improved production stability more than trying to “fix” them with complex imputation strategies.

The Real Lesson

Training-serving skew isn’t a model problem. It’s an engineering problem.

The model trained correctly. The deployment succeeded. The infrastructure worked. But the data pipeline assumptions were fundamentally incompatible between environments.

The fix wasn’t better models. It was better data engineering.

Failure #2: Data Drift That Monitoring Couldn’t See

The Incident

A fraud detection model started flagging legitimate transactions as suspicious. False positive rate jumped from 3% to 12% over six weeks. Customer complaints increased proportionally.

Our drift detection showed… nothing unusual.

What Changed

The model’s input distribution hadn’t drifted. The world had drifted.

A major payment processor changed their transaction metadata format. What was previously a categorical field with 50 distinct values suddenly had 200+ values. Our model had never seen most of them during training.

The Architecture Gap

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ TRAINING DATA (2022-2023) │

│ │

│ Transaction Category: ['retail', 'food', 'gas', ...] │

│ Total unique values: 50 │

│ Coverage: 99.8% of transactions │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ PRODUCTION DATA (March 2024) │

│ │

│ Transaction Category: ['retail', 'food', 'gas', ...] │

│ + 150 NEW values from payment processor update │

│ Coverage: 60% of transactions match training │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Why Standard Drift Detection Failed

Our drift monitoring compared statistical distributions:

# Standard drift detection

def detect_drift(reference_data, production_data, feature_name):

"""

Compares distributions using KL divergence

"""

ref_dist = reference_data[feature_name].value_counts(normalize=True)

prod_dist = production_data[feature_name].value_counts(normalize=True)

kl_div = entropy(ref_dist, prod_dist)

return kl_div > DRIFT_THRESHOLD

The problem? For categorical features with many new values, KL divergence doesn’t capture the semantic shift effectively. The distribution might look similar statistically while being completely different semantically.

What Actually Fixed It

1. Vocabulary Monitoring

Track which values the model has actually seen:

class VocabularyMonitor:

def __init__(self, training_vocab):

self.known_values = set(training_vocab)

def check_production_value(self, value):

"""

Flag unknown categorical values

"""

if value not in self.known_values:

logging.warning(

f"Unknown categorical value encountered: {value}"

)

return False

return True

def get_coverage(self, production_data):

"""

Calculate percentage of known values

"""

total = len(production_data)

known = sum(

val in self.known_values

for val in production_data

)

return known / total

2. Semantic Drift Detection

Instead of just comparing distributions, we monitored coverage:

def monitor_categorical_coverage(feature_name, production_batch):

"""

Track how many production values were seen during training

"""

training_values = get_training_vocabulary(feature_name)

production_values = set(production_batch[feature_name].unique())

coverage = len(

production_values & training_values

) / len(production_values)

if coverage < 0.8: # Alert threshold

alert(

f"Only {coverage*100:.1f}% of production "

f"values were seen during training"

)

3. Graceful Unknown Handling

Default handling for unseen categorical values:

def encode_categorical_safe(value, known_encodings):

"""

Handle unknown categorical values gracefully

"""

if value in known_encodings:

return known_encodings[value]

else:

# Map to 'unknown' category instead of crashing

return known_encodings.get('__UNKNOWN__', 0)

The Real Lesson

Drift detection isn’t just about distribution statistics. It’s about tracking what your model has actually learned.

For categorical features, monitoring vocabulary coverage matters more than monitoring statistical moments.

Failure #3: Label Leakage Discovered After Deployment

The Incident

A loan default prediction model achieved 0.96 AUC during training. After deployment, it was essentially useless — barely better than random guessing.

We had label leakage. And it only became obvious in production.

What Leaked

One of our features was “days since last payment.” During training, we computed this using the full transaction history — including transactions that occurred after the loan default.

In production, we could only compute it using data available before the prediction.

The Subtle Bug

Training code:

# This runs on historical data

def compute_days_since_last_payment(user_id, reference_date):

"""

Computes using ALL historical data

"""

all_payments = get_all_payments(user_id) # Includes future!

payments_before_ref = all_payments[

all_payments['date'] <= reference_date

]

if len(payments_before_ref) == 0:

return 999 # Large default value

last_payment = payments_before_ref['date'].max()

return (reference_date - last_payment).days

The problem isn’t obvious until you realize get_all_payments() returned the complete payment history, including payments made after the default date.

What should have been:

def compute_days_since_last_payment(user_id, reference_date):

"""

Computes using only data available at reference_date

"""

# Only get payments BEFORE the reference date

payments = get_payments_before_date(user_id, reference_date)

if len(payments) == 0:

return 999

last_payment = payments['date'].max()

return (reference_date - last_payment).days

Why This Went Undetected

Cross-validation looked perfect because the leakage was consistent across train/validation splits. The model learned a pattern that was only valid when future data was available.

What Actually Fixed It

1. Point-in-Time Feature Engineering

We enforced strict temporal boundaries:

class PointInTimeFeatureStore:

"""

Ensures features only use data available at decision time

"""

def get_features(self, user_id, as_of_date):

"""

as_of_date: The decision timestamp

"""

# Hard constraint: no data after as_of_date

historical_data = self.db.query(

f"""

SELECT * FROM transactions

WHERE user_id = {user_id}

AND transaction_date < '{as_of_date}'

"""

)

return self.compute_features(historical_data)

2. Production-First Feature Development

We reversed the development process:

- First: Write the production feature computation code

- Second: Replay it on historical data for training

- Third: Validate that both paths produce identical results

# Define production logic first

def production_feature_logic(data_before_decision):

return {

'days_since_last_payment': compute_payment_recency(data_before_decision),

'total_transactions': len(data_before_decision),

# ... other features

}

# Use the same logic for training

def create_training_dataset(historical_users, decision_dates):

"""

Replay production logic on historical data

"""

features = []

for user_id, decision_date in zip(historical_users, decision_dates):

# Get data exactly as production would see it

data_available = get_data_before_date(user_id, decision_date)

# Use the exact same feature computation

user_features = production_feature_logic(data_available)

features.append(user_features)

return pd.DataFrame(features)

The Real Lesson

Label leakage isn’t just a data science problem. It’s a time-travel problem.

If your training features use any information that wouldn’t be available at prediction time, your model is learning to predict the past, not the future.

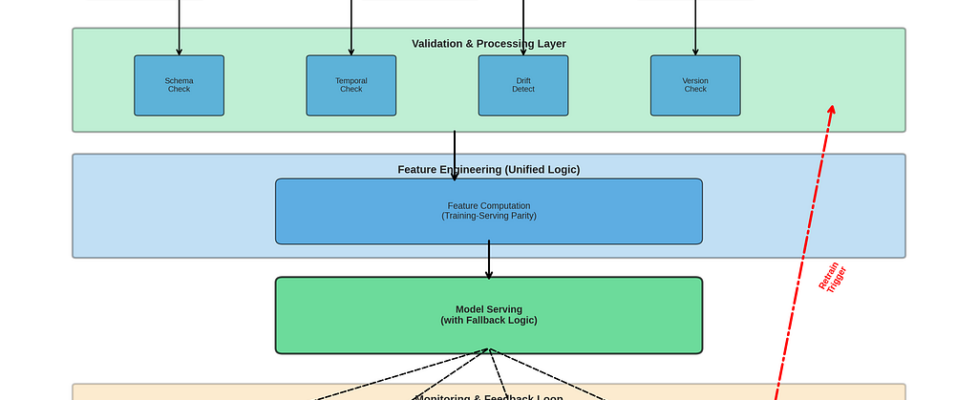

What Actually Prevents These Failures: The Engineering Practices That Worked

After fixing these incidents multiple times, a clear pattern emerged. The solutions weren’t about better algorithms or more sophisticated monitoring. They were about engineering discipline.

Practice 1: Feature Contracts

Treat features like API contracts:

# feature_definitions.yaml

features:

avg_transaction_amount_30d:

description: "Average transaction amount over last 30 days"

data_source: "transactions table"

lookback_window: 30

minimum_data_points: 3

fallback_value: 0.0

computation:

training: "features.offline.compute_avg_amount()"

serving: "features.online.compute_avg_amount()"

validation:

- name: "distribution_match"

threshold: 0.05

- name: "null_rate"

threshold: 0.01

Practice 2: Unified Feature Repositories

One codebase for both training and serving:

feature_repo/

├── __init__.py

├── base.py # Abstract feature interface

├── transaction.py # Transaction features

├── user.py # User features

└── tests/

├── test_consistency.py

└── test_distributions.py

Practice 3: Production-First Development

Step 1: Design feature for production constraints

↓

Step 2: Implement production feature computation

↓

Step 3: Replay production logic on historical data

↓

Step 4: Train model using replayed features

↓

Step 5: Validate training/serving consistency

Practice 4: Continuous Validation

# Runs every hour in production

def validate_production_features():

"""

Automated checks for training-serving consistency

"""

# Sample recent production requests

prod_samples = sample_recent_predictions(n=1000)

# Recompute using training logic

training_features = compute_offline_features(prod_samples)

# Compare

for feature in FEATURE_LIST:

prod_values = prod_samples[feature]

train_values = training_features[feature]

# Statistical comparison

assert_distributions_match(prod_values, train_values)

# Null rate comparison

assert_null_rates_match(prod_values, train_values)

Conclusion: Production ML Is an Engineering Problem

The biggest lesson from these failures is simple: most ML production issues aren’t ML issues.

They’re engineering issues that happen to involve ML models:

- Training-serving skew is a data pipeline problem

- Data drift is a monitoring problem

- Label leakage is a temporal consistency problem

The models themselves were fine. The math was correct. The algorithms worked. What failed was the infrastructure around them.

If you’re building production ML systems, invest more time in:

- Feature engineering discipline

- Training-serving consistency

- Temporal correctness

- Automated validation

And less time in:

- Chasing marginal accuracy improvements

- Complex model architectures

- Hyperparameter tuning

The model that deploys reliably is better than the model that performs slightly better in offline evaluation.

References and Further Reading

- Sculley et al. (2015) — “Hidden Technical Debt in Machine Learning Systems”

- Google’s “Rules of Machine Learning” — #5: Test the infrastructure independently from the model

- Feast Feature Store Documentation — Consistency Guarantees

Thanks for reading! If you’ve encountered similar production failures or have questions about these fixes, I’d love to hear from you in the comments.

What Actually Breaks ML Models in Production: A Fintech Case Study was originally published in Towards AI on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.