The Key to AI Intelligence: Why Transformer Width Matters More Than Depth

“Sweet are the uses of adversity,

Which, like the toad, ugly and venomous,

Wears yet a precious jewel in his head”

— Shakespeare, As You Like It (Act 2, Scene 1)

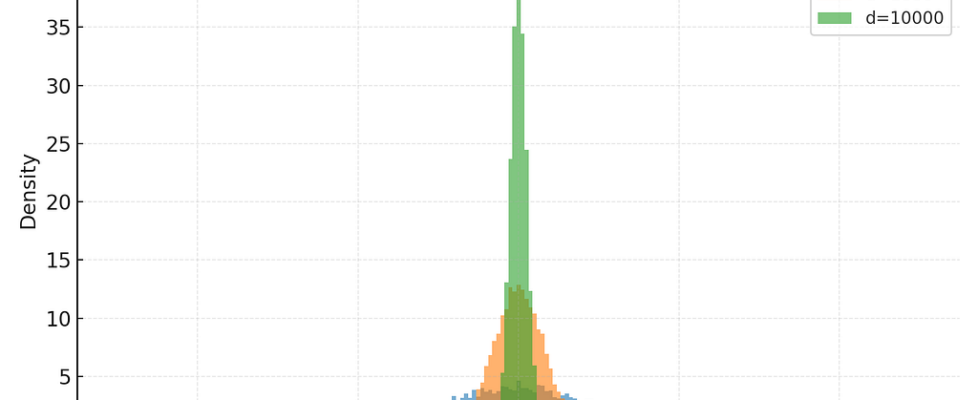

Hyper-dimensional geometry is at the very heart of the transformer architecture. It is forbidding. It’s counterintuitive, odd, even hostile to intuition. It looks nothing like the 3D world we live in. Step into this alien world and you will find not comfort but a complete disorientation: nearly everything is the same distance apart, almost all the volume of a sphere is compressed into a paper-thin layer near the surface. While two random arrows in 3D might point anywhere, in 10,000 dimensions they are almost guaranteed to be orthogonal. Interference vanishes.

Hyper-dimensional geometry is hard to comprehend, but as Shakespeare noted, what seems hostile and forbidding may hide an unexpected blessing.

The blessing of dimensionality

The first to realize that “instead of being a curse, high dimensionality can be a blessing” was Pentti Kanerva (2009). Strange and wonderful things happen in hyper-dimensional spaces:

- Random vectors become almost perfectly orthogonal.

- Noise vanishes into the background.

- You can superpose (add together) thousands of vectors and still recover the originals.

- Memory recall becomes robust, almost like magic.

Transformers — today’s AI workhorses — exploit exactly the same blessing, often without admitting it.

Every token, every attention head, every Q, K, and V is a hyper-dimensional vector. Attention doesn’t work because of mysterious “emergent properties.” It works because geometry in high-dimensional space guarantees it.

- Many modern open-source models (LLaMA-2, Mistral, Gemma, etc.) are in the 4k–8k width range.

- GPT-3 — the famous 175-billion-parameter model from OpenAI — has 12,288 dimensions. That means every token in GPT-3 lives as a point in a 12k-dimensional space.

- Grok is estimated by the community at 32,768 dimensions, however this is not officially confirmed or denied by xAI.

- For GPT-4 and GPT-5, OpenAI has not revealed the hidden size at all — and yet, if width is the substrate of thought, this is the very number that might matter most.

Why width is the substrate of thought

When you widen the hidden states — from 512 to 4k, to 8k, to 12k — everything changes.

- Orthogonality sharpens. Random vectors don’t interfere with each other.

- Roles (subject, verb, object, modifier) can be bound to role fillers without overlap.

- Nested propositions (“if A and B then C”) remain decodable, step after step.

- Multi-step reasoning chains don’t collapse into mush.

This is not just math trivia. It’s the algebra of reasoning itself: binding, bundling, unbinding. And these vector operations only stay clean in high dimensions.

Ramsauer et al. (2020) even showed that attention is nothing but a modern Hopfield network — a form of associative memory. And memory capacity scales with dimensionality.

Mapping HDC onto Transformers

The resemblance is not accidental. The core operations of Hyper-Dimensional Computing (HDC) map directly onto Transformers / Attention architecture. Both frameworks rely on the same principle: dimensionality makes association, composition, and recall reliable. Without wide enough vectors, interference overwhelms signal and reasoning collapses.

- Each concept (word, symbol, or token) is represented as a very long vector — thousands of numbers. The high dimensionality makes it easy to keep different items nearly independent, like giving each token its own “address” in a vast space. When the hidden dimension d is large, token representations (embeddings, hidden states) are nearly orthogonal. This prevents spurious overlap when the model mixes signals through attention or feed-forward layers. Attention weights can reliably learn to isolate relevant tokens instead of blurring everything together.

- Binding combines two pieces of information — like role = SUBJECT and filler = DOG. In Transformers, the analogy is a dot product between a query (what we’re looking for) and a key (what’s available). The bigger the dot product, the more strongly they match. Attention heads dynamically learn roles (one head may track subjects, another modifiers, etc.), and keys/queries act like the role/filler vectors. Binding is learned, not predefined, but the underlying principle is the same — role/filler pairings don’t interfere because high-dimensional space keeps them distinct.

- Bundling mixes many items into one vector. Decodability holds as long as the bundle size is within capacity for dimension d: SNR degrades roughly with the square root of k for k bundled items. Larger d preserves accuracy. Transformers do something similar: they blend multiple candidate values Vj, giving each one a weight according to how well its key matches the query. The softmax ensures the weights are positive and add to 1, so the result is a smoothed “average of answers”.

- After bundling, the vector may be noisy or “in between.” Cleanup memory finds the stored prototype vector that’s closest, snapping it back to something recognizable. In Transformers, layer normalization and residual connections act like a cleanup mechanism, stabilizing the noisy intermediate computations.

- Given a cue (query), associative recall pulls out the most related memory. In attention, the query looks across all keys, assigns weights, and then pulls back the relevant values V. It’s like asking: “Which past words are relevant to predict the next word?”

Why we stopped widening

If width is so important, why don’t we see 64k-wide models and beyond?

The short answer: cost. FLOPs scale as the square of width. Jumping from 8k to 32k dimensions is a 16× increase in compute.

Kaplan et al. (2020) showed that neural networks obey smooth scaling laws. But those curves don’t reveal why the models work — they just show predictable improvements with size. To most engineers, width looked like “just another knob.”

And benchmarks don’t help. Tasks like MMLU or GSM8K don’t stress multi-step reasoning chains, where dimensionality really shines. So labs stick to the 4k–8k range — not because wider is useless, but because the economics don’t reward it.

Why we must widen again

Width is not a luxury — it’s the very substrate of intelligence.

As context windows explode to 128k and beyond, bundling capacity will demand wider spaces. As we push deeper into theorem proving, complex program synthesis, and scientific reasoning, we’ll need long chains of nested composition that only high d can sustain.

The next leap in AI intelligence won’t come just from stacking more layers or pouring in more data. It will come from giving thought itself a higher dimensional space to breathe.

Looking back, it almost feels obvious. Intelligence in transformers doesn’t come from the magic of “attention.” It comes from the geometry of hyper-dimensional space itself — the very blessing Kanerva described over a decade ago.

We may one day realize that the real secret ingredient of AI wasn’t depth, or data, or parameters. It was width all along.

The hardware cost of wider thought

Redesigning hardware for ultra-wide models will reshape the economics of AI — but not always in the way people assume.

- With current GPUs, widening is brutally inefficient. A 4× jump in width means ~16× more computation, ~4× more memory, and wasted cores that sit idle. Costs grow far faster than capabilities.

- If accelerators were built for wide vectors — with processing units and memory tuned for 32k–64k dimensions — the cost per useful operation could fall. Silicon would finally be doing the work it was built for.

- Wider models demand bleeding-edge memory (HBM3, CXL). Expensive today, yes — but as demand scales, vendors invest, capacities double, and prices drop. It’s the same learning curve GPUs rode a decade ago.

- GPUs themselves were once niche graphics toys. Deep learning turned them into the backbone of AI, and cost per FLOP plummeted. The same cycle could repeat for ultra-wide AI accelerators.

So the real question is not “can we afford width?” but “can we afford to ignore it?” If width is the substrate of intelligence, then the cheapest intelligence per dollar may one day come from hardware built for wider thought spaces.

References

- Kanerva, P. (2009). Hyperdimensional Computing: An Introduction to Computing in Distributed Representation with High-Dimensional Random Vectors. Cognitive Computation.

- Kaplan, J., et al. (2020). Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models. arXiv:2001.08361.

- Ramsauer, H., et al. (2020). Hopfield Networks is All You Need. arXiv:2008.02217.

The Key to AI Intelligence: Why Transformer Width Matters More Than Depth was originally published in Towards AI on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.