LLMs, MCPs, and Agents in Decision Intelligence

Where language models add leverage — and where they deliberately stop

TL;DR:

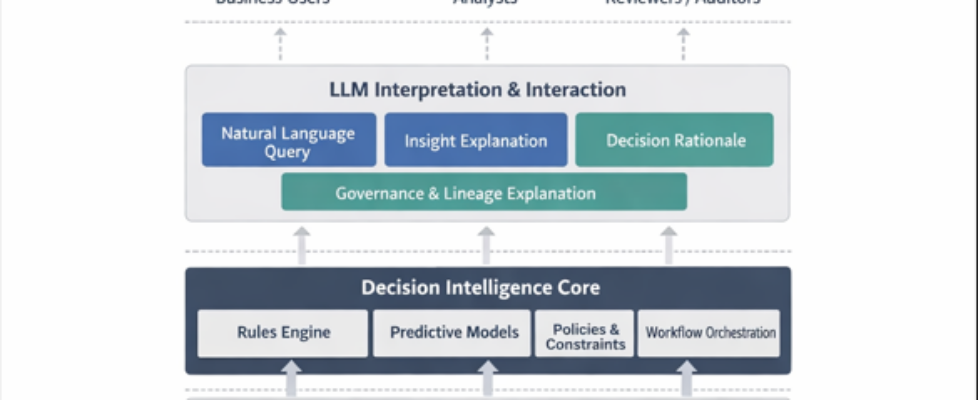

Large Language Models add the most value in Decision Intelligence systems when they improve how decisions are understood, not when they take over how decisions are made. In mature DI setups, LLMs act as an interpretation layer — enabling natural language querying, automated insights, clearer metadata, and better explanations — while decision authority remains with deterministic rules and models. MCPs and agents help scale this safely by controlling access and coordinating tasks without shifting control.

Introduction

Decision Intelligence (DI) systems are increasingly adopted in organisations that have already stabilised their analytics, modelling, and operational workflows. In such environments, decisions are no longer implicit side effects of dashboards or reports; they are explicit artefacts shaped by rules, models, and policies.

This article examines what changes after that point — when Large Language Models (LLMs) are introduced into an already functioning DI setup.

The scope here is deliberate. This is not about consumer chatbots, end-to-end autonomous systems, or experimental agentic decision-making. The focus is enterprise decision systems where accountability, auditability, and stability are non-negotiable, and where LLMs are introduced to improve usability rather than redefine authority.

In these systems, LLMs do not replace decision logic. They do not substitute for predictive models or policy engines. Instead, they alter how humans interact with the system — how information is accessed, how outcomes are interpreted, and how changes are surfaced. Architecturally, LLMs sit alongside decision outputs and data layers, acting as an interaction and interpretation layer rather than a decision engine.

A useful way to frame this role is that LLMs change how decisions are understood, not how they are authorised.

For example, consider a loan approval system where eligibility rules, risk thresholds, and regulatory constraints are already defined. When an LLM is added, it does not approve or reject applications. The outcome remains identical. What changes is the system’s ability to explain that outcome — summarising which inputs mattered, which rules applied, and how risk signals were evaluated. Decision logic remains untouched; reasoning becomes visible.

Once this distinction is clear, the rest of the LLM use cases in a Decision Intelligence system fall into place.

Natural language access to data and decisions

Natural language querying is often the first LLM capability introduced into DI systems. Business users typically know what they want to ask — about inventory risk, approval rates, or customer eligibility — but not how to express those questions in SQL or navigate multiple dashboards.

In practice, the LLM translates questions into approved queries against existing BI systems and decision outputs, returning answers in plain language or simple tables. The key point is that the LLM queries decisions and their inputs; it does not infer or modify outcomes.

This pattern appears in platforms such as ThoughtSpot, Microsoft Fabric (via Copilot), and conversational interfaces layered over Tableau. In each case, the LLM improves access without altering decision logic.

Automatic insights instead of routine reports

Many enterprise reports exist primarily to answer recurring questions: what changed, what deviated from expectations, or where attention is needed. LLMs reduce reliance on such reports by generating short, contextual explanations directly.

Instead of reviewing multiple dashboards, users may receive summaries explaining that approval rates dropped due to a specific segment shift, or that demand exceeded forecast for a subset of SKUs. The analytics that detect these changes already exist; the LLM converts signals into explanations.

Tools such as Narrative Science, Sisu Data, and Tellius illustrate this approach. The insight is generated without introducing new decision thresholds or business rules.

Metadata as the foundation for effective LLM use

A recurring constraint in DI systems is not model accuracy but input comprehension. Metadata is often fragmented or outdated, leading to confusion about what fields represent or which metric definitions feed decisions.

LLMs help by interpreting catalog metadata, sample values, and usage patterns to produce explanations that bridge technical and business language. This improves onboarding and reduces misinterpretation of decision inputs.

Platforms such as Alation, Collibra, and Atlan increasingly use LLMs in this capacity.

More importantly, this metadata layer underpins other LLM capabilities. Natural language querying works reliably only when field semantics and metric ownership are clear. Automatic insights depend on knowing which changes are meaningful versus expected. Without strong metadata, LLMs may remain fluent but unreliable. With it, they become dependable components of the DI system.

Governance and lineage, explained rather than bypassed

Governance and lineage mechanisms already exist in mature DI environments, but they are rarely transparent to users. LLMs are increasingly used to explain why access is restricted, which policies apply, or what downstream assets will be affected by a change.

In this role, the LLM does not enforce policy or modify lineage graphs. It reads from them and presents explanations in accessible language. Platforms such as Immuta, Privacera, Microsoft Purview, and OpenLineage provide the authoritative controls; LLMs make them understandable.

Decision explanations and audit support

In regulated environments, decisions must often be explained to auditors, customers, or internal reviewers. When a price changes or a loan is declined, the decision already exists. The LLM’s role is to assemble inputs, applied logic, and evaluation results into a coherent explanation.

Model monitoring platforms such as Fiddler AI, Arize AI, and Arthur AI increasingly use LLMs for this purpose. Transparency improves without shifting decision authority.

Why not let LLMs authorise decisions?

Some architectures explore allowing LLMs to directly authorise or modify decisions, particularly in consumer-facing or experimental systems. This article does not argue that such designs are invalid in principle.

However, in enterprise DI environments where accountability, auditability, and reproducibility matter, separating authorisation from explanation remains a practical constraint. Deterministic logic enables rollback, audit trails, and policy enforcement. LLMs add leverage by improving interpretation without destabilising these guarantees.

MCPs and agents as control and coordination layers

As LLM usage expands, controlling how models access system context becomes critical. Model Context Protocols (MCPs) formalise how LLMs invoke approved tools and read authorised views, ensuring explanations are grounded in sanctioned interfaces.

Agents — LLMs combined with memory and orchestration — are useful for multi-step interpretive tasks such as assembling reviews or monitoring trends. In DI systems, their value lies in coordination, not autonomy.

Synthesis

In mature Decision Intelligence systems, LLMs function best as interpretive infrastructure. Models evaluate options, rules constrain behaviour, workflows execute outcomes, and LLMs make those processes intelligible. MCPs regulate access; agents orchestrate interaction.

This separation is not ideological. It reflects how enterprise systems remain stable while becoming more usable. LLMs add the most value when they surround decisions, illuminate them, and leave authority exactly where it already belongs.

LLMs, MCPs, and Agents in Decision Intelligence was originally published in Towards AI on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.